![]()

Hawaiiana teacher

|

Hindus and

Hawaiians

build truce

Both sides hold the Wahiawa

site in high esteem, although

they differ in how they view it

The "healing stones" of Wahiawa drew hundreds of pilgrims in the 1930s, but few local people or tourists find their way to the off-the-beaten-path location these days.

Two separate groups of people -- one Hawaiian, the other Hindu -- have assumed caretaker roles of the stones and reached an edgy truce because both consider them sacred.

![]()

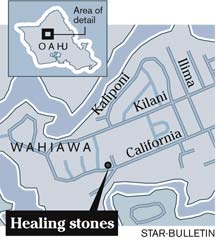

The three boulders are anchored in cement on a small city-owned plot at 110 California Ave. The story goes that they are parts of one huge stone that broke when it fell off a wagon while being moved from the location of the Hawaiian birthing stones a mile away off Kamehameha Highway. It was originally found in Kaukonahua gulch by a Waimea Sugar Co. worker.

"We go clean it once or twice a month," said Lani Kiesel, who has lived nearby for 40 years but just awakened to the site's importance. "If it looks wilted, I will clean it out. We've found candles melted all over the stones."

Kiesel and Elithe Kahn started their work after finding the stones "smothered" with oily residue.

"Neglected sites are being taken care of as part of the resurgence of Hawaiian awareness," said Kahn, who teaches a class in the Hawaiian breathing discipline of ha. "Kupunas have taken up the cause. It's important that we introduce young children to the history."

The women have produced leaflets that identify the stone by its Hawaiian name, Keanianileihuaokalani.

"We implore people whose religious practices incorporate oiling the stone as a form of adoration to abstain from this foreign practice," says their leaflet left for visitors.

Several Hindus anoint themselves with smoke from sacred candles, part of the ceremonial cleansing of the stones.

"Each group is trying to respect it in our own way," Kahn said. "We don't want it to be a conflict; that was not our intention. We have gone through phases from being incensed that this was happening to it, to having a dialogue."

Kiesel and Kahn attended the Hindus' monthly service Sunday that focused on the 6-foot-fall stone. "We were pleased and content with what was going on. They are adoring it. These people would never hurt the stone."

Teacher Eda Kaneakua has made the healing stone a project for her sixth-graders at Wailupe Valley Elementary School. After finding only minimal references to it in books and on the Internet, they decided to create a Web page to tell its story. They are selling plastic bracelets with the stone's name.

"It is planting seeds in the kids; we need future caretakers of these sites," said Kaneakua.

Alice Greenwood of Nanakuli joined their effort recently and is upset at the state of the stone. She distributes her own leaflet criticizing people who oil the stone: "It is not a Hawaiian custom, and it suffocates the healing stone, hampering its ability to breathe and heal."

Greenwood said she has tried to get the Office of Hawaiian Affairs involved in protecting the site.

S. Ramanathan, a University of Hawaii pharmacology professor, has assured the Hawaiians that Hindus do not put oil or candle wax on the stone.

Dr. S. Ramanathan, left, and Dharm Bhawuk performed a ritual to cleanse the stones.

While the Hawaiians believe the stones have healing powers, Hindus see it as a deity.

"We know he is a Hawaiian god," Ramanathan said. "Since he resembles Shiva, we worship him, too." He and UH business professor Dharm Bhawuk led the Hindu service attended by about 100 people.

He said the structure that encloses the stones on three sides was already there in 1988 when recognition of the Shiva image led Hindus to the site. "It was a dilapidated concrete shed," Ramanathan said. The Sawney family invested $60,000 to turn the shed into a white marble shrine, he said.

The Hawaiian women want the structure either removed or opened to the sky so the stones are exposed to their natural elements of sun and rain.

The healing stone's history is somewhat cloudy. It was found on Waialua Sugar Co. land and was hauled to the Kukaniloko birthing site, where Hawaiian alii women gave birth, after a Hawaiian man told plantation official George Galbraith that the stone has sacred healing properties.

Dozens of people gathered Sunday in Wahiawa for a Hindu service that focused on the "healing stones."

The reputed healing power of the stone drew crowds of visitors, many obviously ill, according to a history of the Daughters of Hawaii written by Barbara Del Piano. Candles were placed on it, incense was burned, food offerings were left and "at the height of the frenzy, $1,000 of cash was left each month," said McGuire.

The tallest boulder's provocative shape did not escape the eye of Christian ministers of the day, who accused the Daughters of Hawaii of fostering "abominable worship" of a "lascivious image."

The popular attraction drew vendors and the debris drew rats. People in Wahiawa considered it unsanitary, and 400 people signed a petition to the Board of Health.

World War II drew away attention, and interest in the healing stone died down. Daughters of Hawaii relinquished its caretaker role to a Hawaiian civic club, McGuire said.

In 1971 the Wahiawa Community and Businessmen's Association asked the Hawaii Visitors Bureau to put up a sign to again call public attention to the "Healing Stone of Wahiawa."

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]