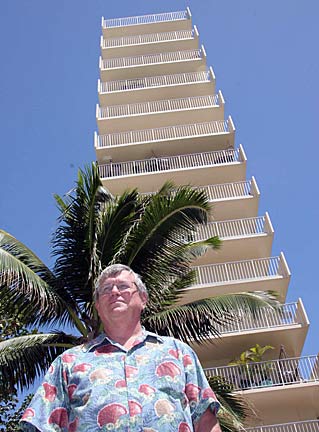

Developer who converted the Diamond Head Beach Hotel to a condotel in the mid-1990s.

|

No rooms

at the inn

Seeking better returns, more

Hawaii hotels are making

the switch to time-shares,

condos or "condotels"

Hot sales of homes and lagging demand for off-beach budget hotel rooms are fueling a cycle of condominium and time-share conversions that could change the architecture of Hawaii's visitor industry.

In the past several years, Outrigger Hotels & Resorts, the state's largest locally owned hospitality company, has lost about 29 percent of its 8,300 rooms in Hawaii to conversions. The Ohana Hobron, the Ala Wai Tower and the Ohana Surf, once managed by Outrigger, are among the many budget hotels that have morphed into "condotels," time-shares or residential condos as developers and owners seek higher returns on their investment.

"We've lost 1,000 rooms in the last three years and we'll probably lose another 800 in the near future -- the Ohana Waikiki Surf and Ohana Waikiki Surf East and the Ohana Maile Sky Court are being eyed by condo developers," said David Carey, Outrigger's president and chief executive.

In January, Outrigger took 478 rooms out of its rental pool when it shut down the Ohana Reef Tower, which will become a Fairfield Resorts timeshare. The company will also temporarily remove another 880 rooms from its rental pool in April when it begins the conversion of the Ohana Waikiki Tower and the Ohana Village into an all-suite hotel.

Strong demand for time-shares prompted Marriott to increase the number of units at its Maui Ocean Club at Kaanapali.

While condotels -- condominiums that allow owners to rent out their units like hotel rooms -- combined with hotel rooms and time-share units, have been around in Hawaii since the 1960s, the concept began taking off about five years ago, said Hawaiian Island Homes Ltd. developer Peter Savio, who was at the front of the recent cycle of conversions with his transformation of the boutique Diamond Head Beach Hotel into a condotel in the mid-1990s.

"It was tremendously successful," Savio said. "The property sold out in a day."

Savio, who estimates roughly 4,000 rooms in the state's pool of more than 70,000 have been converted or slated for conversion since 2000, said the rapid growth is similar to what's going on in other destinations such as Los Angeles, and Key West, Miami and Cocoa Beach, Fla.

Many of the people associated or touched by the Hawaii visitor industry say the movement will strengthen tourism by increasing capital investment, upgrading the product and diversifying the market.

"A lot of the buildings that have been converting were marginal for years," Savio said. "What's coming out of the process is a better product."

But others are worried the change could damage the state's group and business travel markets. Some also fear that the state's high price of housing could result in more and more condotel rooms being scooped up for use as residential housing or as vacation homes for aging baby boomers.

While conversion has funneled needed capital into tired properties, Carey said, the change in some cases has resulted in less room inventory, fewer jobs and a decline in state revenues.

The Hawaii Tourism Authority has commissioned Joseph Toy, president of Hospitality Advisors LLC, to study the extent and impact of the state's conversions.

The Ala Moana Hotel is among the latest conversions as new owner Crescent Heights plans to convert it to a "condotel."

Condotels, which are attractive to families and longer-staying travelers, typically aren't used by large groups or business travelers, she said.

"The study is part of our strategy to determine our ability to meet our goals where the convention center is concerned and how best to market the product," Wienert said.

If the trend removes too much hotel inventory it could make it difficult for the state's visitor industry to attract business meetings and conventions, she said.

"If enough rooms come out of full-service inventory you want to be sure that you have enough space to handle the large-term convention business. That's an issue that's out here as more and more conversions are taking place," said Murray Towill, president of the Hawaii Hotel & Lodging Association.

While some visitor industry players fear the unknowns in the long-term impacts of conversions, others believe the concern is misplaced, said Kelvin Bloom, president of Aston Hotels & Resorts, which manages about 20 resort condominiums and condotels in the Islands.

"There's a bit of hysteria surrounding it, but on a more global basis the change won't be that significant," Bloom said. "The biggest impact that we've seen has been positive -- a lot of new capital is being injected into tired properties, which has improved the level of guest experiences."

In the end, most conversions wind up back in the short-term vacation rental pool, Savio said, adding for every 4,000 or so converted units all but about 200 will remain rentals.

But the conversions still make it more difficult for property managers to court group business at these properties because condotel management contracts are typically short term and the conventions books years in advance, Carey said.

"It's a gamble," Carey said. "We can't look ahead and tell you how many of the rooms that we'll have in our rental pool. The current business model doesn't give you any certainty of your future in a product."

For instance, when Outrigger agreed to manage the Luana Waikiki after it was converted into a condotel, there was no guarantee how many of the 200 or so owners would elect to use their services, Carey said.

About 175 Luana owners signed up for Outrigger's management services.

"The state needs to step up to the plate and determine how to make this market more stable," Carey said, adding that it could be time for the government to consider approving regulatory legislation or offering hotels incentives to renovate.

Despite the risk of managing converted properties, the chance to earn revenue without major capital outlays has enticed major brands including Outrigger, Marc Resorts, Cendant Hotel Group, Starwood, Ritz-Carlton and Four Seasons to begin bidding on these contracts.

While Marriott is not managing any condotels in Hawaii, further diversifying the brand's product mix is becoming more attractive, said Stan Brown, Marriott International vice president for the Pacific Islands.

"Business in general will go toward the best use of an asset. We would potentially look at managing a condotel in Hawaii if it were the right place at the right time for us," Brown said.

Managing a condotel wouldn't be Marriott's first foray into non-traditional accommodations.

In the 1990s, Marriott eliminated some hotel inventory to build time-shares, a decision that has added economic stability, Brown said.

The company operates four time-shares in Hawaii, including the Kauai Marriott Beach Club, the Marriott's Waiohai Beach Club, the Ko Olina Beach Club and Marriott's Maui Ocean Club at Kaanapali.

Strong market demand prompted Marriott to rebuild the Kauai Marriott Beach Hotel, which was damaged in Hurricane Iniki, as a time-share. The success of that project led to the company's decision to reduce hotel room inventory in Kaanapali by increasing the number of time-share units at the Maui Ocean Club.

"We've grown our hotel business along with our vacation club business," Brown said, adding that the company, which had four island hotels in 1999, has since expanded to 11 resorts and 4 time-shares. "The key is having a balance."

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]