|

View from

the Pew |

The Ten Commandments

Isle religious leaders reflect on the

conflicts caused by differences in

faiths’ moral codes

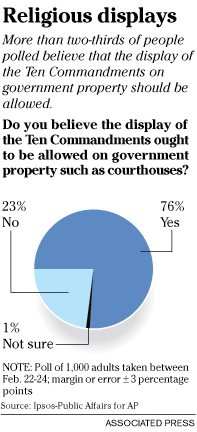

The Ten Commandments went before the U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday. The justices are pondering whether the Old Testament code is religious doctrine being imposed on secular society when displayed on plaques in Kentucky courthouses and a stone monument at the Texas state Capitol.

People from some of Hawaii's many faiths contemplated the question this week. But they were not vehement about the perceived unconstitutionality of the public display as were several national church groups. Filing briefs as friends of the court were the national Interfaith Alliance and Jewish, Hindu and Baptist organizations.

People from some of Hawaii's many faiths contemplated the question this week. But they were not vehement about the perceived unconstitutionality of the public display as were several national church groups. Filing briefs as friends of the court were the national Interfaith Alliance and Jewish, Hindu and Baptist organizations.

"Every religion has its set of moral codes, and they are very similar," said the Rev. Yoshiaki Fujitani, president of the Buddhist Promotion Society. "The problem is when one group declares their set as the authentic one. The issue is not content, but in the way it is couched."

Buddhism has 10 precepts that are sometimes compared with the biblical Ten. They call a Buddhist to abstain from harming living beings, taking things not freely given, sexual misconduct, false speech and "intoxicating drinks and drugs causing heedlessness." Five others apply to monks' abstention from greed, gluttony and frivolous behavior.

Hinduism also has precepts that guide human behavior, said University of Hawaii business professor Dharm Bhawuk. A set of five vows or "yama" that have become well known in the West because of the popularity of yoga are nonviolence, truth, not stealing, celibacy and not collecting material possessions. Then there are five rules or "niyam" providing for cleanliness, contentment, self-discipline, study of scriptures and "devotion, offering everything you do to the Lord," said Bhawuk, who leads a monthly Hindu worship service. "All of these apply in mind, word and deed."

A monument of the Ten Commandments is shown on the grounds of the Texas state Capitol in Austin.

"They are not universal," said University of Hawaii religion professor Andrew Crislip. "Religions certainly agree on not killing, not stealing, not coveting ... but there is also the thing about no graven images.

"In the ancient world, the ban on idols was interpreted as no images of humans and animals. That's why Jewish coins would have a floral motif." Islam has a similar ban that is reflected in its art, he said. But the early Christians, Catholic and Orthodox, depicted God, Jesus and saints in formulaic icons and the evolving imagery of Western art. And images of Buddha and the various Hindu gods abound in those religions.

Fujitani said: "Buddhism was charged with being idolatry. People did not understand the Buddha image is simply a symbol; it is not worshipped as an idol."

Crislip pointed out that "Christians do not keep the Sabbath" on the day specified and not in the rest and reverence demanded by God.

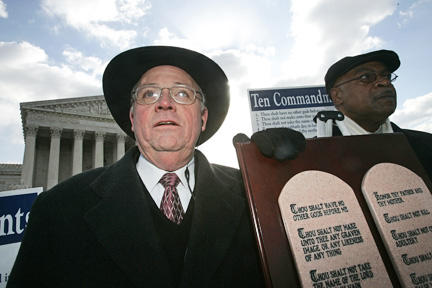

The Rev. Gary Dull of Altoona, Pa., left, and the Rev. Phillip Johnson of Martinsville, Va., hold a copy of the Ten Commandments as they and other Christians rally outside the U.S. Supreme Court.

"I think it is an issue of genuine concern," Crislip said. "I don't think the Ten Commandments have any place in front of a courthouse."

The Rev. John Bolin, a retired Chaminade University professor and administrator, sees the Ten Commandments display as a symbol of the law-abiding society Americans wish they had.

"I would think the general religious population would say it is not a question to challenge you to embrace a religion, but to embrace a way of relating to one another," said the Catholic priest.

"One of the aspects of the development of law over the centuries has been based in religion. The court of law is there to help us to relate with each other appropriately. I think it is significant to have the Ten Commandments displayed near a courthouse," Bolin said.

In Hawaii the issue of a religious display on public property was raised briefly two years ago when the city spent $135,000 to erect a 26-foot replica of a famous Hiroshima torii gate near the University Avenue-King Street intersection in Moiliili.

"Shinto people say it is a religious symbol," Fujitani said. In the ancient Shinto religion of Japan, "the torii is a sacred gate through which one passes into a sacred compound."

The display remains, with the prevailing view that it is a cultural monument marking the contributions of Japanese immigrants to Hawaii, the early development of Moiliili by those immigrants and Honolulu's sister-city relationship with Hiroshima.

On Oahu this torii gate in the triangle at King and Beretania streets near University Avenue is viewed as a cultural monument, but also by Shinto people as a religious symbol.![]()

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]