Sulfur from volcano

raises Big Isle

health concerns

A study finds higher risks of lung

ailments downwind of Kilauea

|

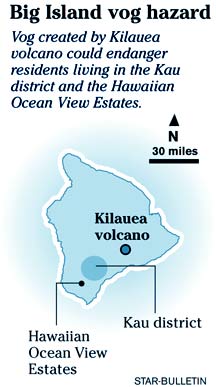

Big Island residents living downwind from Kilauea volcano could face elevated risks of respiratory or cardiac problems from exposure to high levels of sulfur dioxide and aerosol particulates, researchers said yesterday.

During a three-week study of average volcanic activity in 2003, researchers found that daily average sulfur dioxide levels in Ocean View and the Kau district south of Kilauea were about 17.8 parts per billion. The minimal risk level is 10 parts per billion in a 14-day period, according to guidelines set by the U.S. Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

![]()

Sulfur dioxide gas can eventually form a haze, commonly referred to as volcanic fog or "vog" in Hawaii.

"What we found is some cause for concern," said Bernadette Longo, a recent doctoral graduate in public health at Oregon State University and a lead author in the joint study by researchers from Oregon State and the University of Hawaii published in the March issue of the journal Geology.

Longo hopes to publish a second paper chronicling the health problems of longtime residents in three communities south of Kilauea, where as many as 3,000 people live.

"Monitoring the air quality was Part A of the study, in a way," Longo said. "The next step is the epidemiology study, which is in the process of peer review." The study would be the first to look at chronic effects in adults downwind from Kilauea during prevailing tradewinds.

The unfunded study examines the dispersal pattern of emissions from the United States' most active volcano. It was conducted in late summer, when volcanic pollutant concentrations on the Big Island are normally highest.

Tradewind conditions, which are typical, push most of the tainted air out to sea, but light or variable winds concentrate most of the pollution over southern sections of the island. The pollutants generally linger over the ocean in the morning and move inland during the afternoon, Longo said.

"There has been ongoing monitoring at the volcano itself and the station on the Kona Coast, but not much has been done in understanding the distribution of the gas plume as it comes out of the vent," said Anita Grunder, a professor in Oregon's Department of Geosciences and an expert in volcanism who is one of the study's authors.

The Hawaii Department of Health measures sulfur dioxide and particulate levels in Kona and Hilo. The public can access some of the information online, said Lisa Young, of the department's Clean Air Branch.

Respiratory ailments on the Big Island have not been linked decisively to the volcano, since molds and cockroach dust could also be the source of such problems, said Tamar Elias, a chemist at the U.S. Geological Survey's Hawaiian Volcano Observatory.

"This is work that needs to be done, and it's good that someone has taken the initiative to link both the health response and the exposure to volcanic products," Elias said.

Kilauea, which has been erupting since Jan. 3, 1983, is the top single producer of sulfur dioxide in the nation.

No recorded basalt eruptions in the United States have lasted as long, Grunder said. Lava-producing basalt volcanoes, such as Kilauea or Masaya in Nicaragua, can release large amounts of sulfur dioxide into the lower atmosphere, even when not erupting.

www.geosociety.org

Department of Health Air Quality Data:

www.state.hi.us/doh/air-quality

Hawaii Volcanoes National Park:

www.nps.gov/havo/

U.S. Geological Survey:

hvo.wr.usgs.govhvo.wr.usgs.gov

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]