WORKING HARD

TO MEET SCHOOL GOALS

|

Committed

to education

Forty isle schools will learn

this week if they've met federal

goals or must be "restructured"

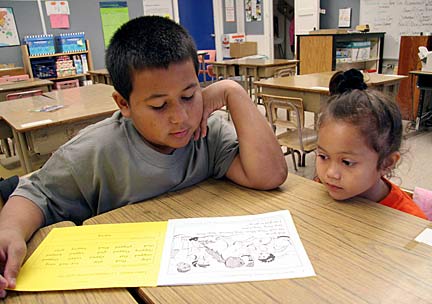

Ten-year-old Brazen Malong shows up early at Palolo Elementary School every day. The playful youngster is struggling to meet academic standards himself, but he chooses to come at 7:30 a.m. for his little sister's sake.

"So I can teach my sister how to read," he said simply, on one recent morning as he joined other fifth-graders who volunteer to tutor younger children at the school.

Brazen's commitment to educating 5-year-old Kalinani may not show up yet on the test scores at Palolo. But stories like his give teachers and staff hope, despite the prospect of sanctions under the federal No Child Left Behind law looming over this well-maintained campus.

This week, 40 high-poverty schools across the state, including Palolo, will find out if they must be "restructured" because of low test scores, a penalty that requires fundamental changes in governance and instruction. (See accompanying story.)

The teachers at Palolo face special challenges, with half their students learning English as a second language and 95 percent of them poor.

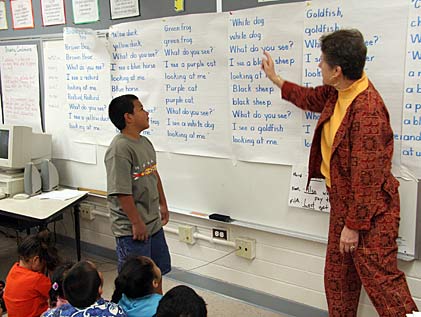

But the school has managed to bring its test scores up with long hours, new teaching strategies, curriculum changes and three different tutoring programs.

Last year, 26 percent of Palolo's students were ranked proficient in reading, up from 14 percent the year before, and 9 percent made the grade in math, up from 2 percent. Still, it wasn't good enough to meet academic targets, and the school was chalked up as a failure under the federal law's strict grading system.

Palolo Elementary fifth-grader Brazen Malong does some reading with the help of academic coach Nancy Hansen-Krening.

Even if the school manages to get a reprieve from "restructuring" by showing significant progress in recent months, the benchmarks for success on the next month's statewide tests will rise. Instead of needing 30 percent of their students proficient in reading and 10 percent in math, the figures jump to 44 percent and 28 percent, respectively.

The No Child Left Behind law demands that students who are learning English as a second language and special-education students meet the same academic benchmarks, which rise on a steady timetable until 2014, when 100 percent of students are expected to be proficient.

"A huge body of research shows that it takes anywhere from five to 10 years to think in another language," said Hansen-Krening, a specialist in multicultural education. "But after one year, they're expected to take that test."

Last week, the National Conference of State Legislatures issued a report denouncing the No Child Left Behind law as unrealistic, unworkable and even unconstitutional.

The nonpartisan group, which represents the 50 state legislatures, asked for more flexibility in measuring school success. But the Bush administration reiterated its support for the law, and Congress is not due to revisit the issue until 2007.

In the meantime, schools are doing what they can to bring their students along. Across the island from Palolo Valley, at Nanakuli High and Intermediate School, teachers in all subjects are pitching in to help bring kids up to speed for next month's math and English tests. Social studies, science and even physical education teachers are incorporating a quick dose of math and English into their daily routines.

"All of our classes give us two problems each in English and math," said eighth-grader Maliea Moe. "It's OK because it's going to benefit us in the tests."

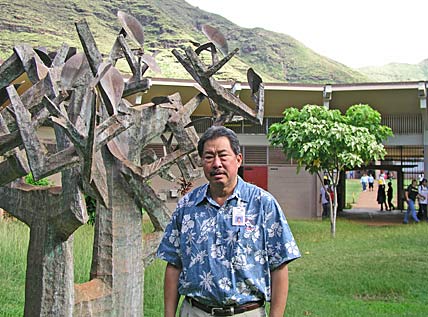

Levi Chang, principal of Nanakuli High and Intermediate School, says that on average 13 percent to 24 percent of students at his school are absent on any given day.

"Education in our community, for most families, that's not their top priority," Chang said. "The top priority here is survival. ... If there's no parent involvement at home, it's hard for the school to be the educator as well as the ad litem parent. That's a problem for all my teachers."

Efforts to adopt research-based teaching strategies, such as America's Choice, have been stymied by staff turnover at Nanakuli.

An audit cited a lack of qualified teachers, large class size, students arriving unprepared, a lack of parental support, behavior problems and high numbers of students in special education. Only 30 percent of seventh-graders arrive at this 60-acre campus at or above grade level in reading comprehension.

The school has altered its schedule to boost time for reading. Teachers have undergone training to hone in on what needs to be covered each quarter.

And counselors and teachers are volunteering to stay after school to tutor.

"The whole school is working really hard. They're giving 110 percent, and at this point, we're all getting exhausted," said Gavin Tsue, vice principal for the middle school at Nanakuli. "But they're putting in extra effort to help the kids prepare for this test."

Nanakuli students have shown some improvement, but are starting from such a low point, especially on the rigorous math portion of the Hawaii State Assessment. On the last state test, 19 percent were ranked proficient in reading, up from 10 percent the year before, and just 3 percent were proficient in math, compared to 1 percent the previous year.

While the focus is on those test scores, the course that most excites eighth-grader Moe is science. Her class is piloting a hands-on, culturally relevant curriculum that has students exploring the watershed of nearby Makua Valley and testing water quality at the ocean. It was designed by the University of Hawaii Center on Disability Studies and Alu Like.

Moe's science teacher, Rick Jenkins, an Alabama native in his first year of teaching, said he appreciates the program just as much as she does.

"You have to really motivate students to learn," he said. "You have to get their attention. The kids really relate to what we're teaching."

At Palolo, the staff also has to go to great lengths to get some students interested in school. When kids don't show up for class, Counselor Alison Higa or Principal Ruth Silberstein go to their homes to get them. Many of the families are Micronesian and Marshallese and are not used to compulsory education, and may not be literate even in their own language.

The cultural gulfs can be considerable. Coaxing parental involvement is a challenge. Silberstein called one father only to have him explode in anger for the intrusion.

"I wanted to compliment him because his child did something nice, by helping another student," Silberstein said. "The fact that I even called the home upset him."

"I think that's why I'm all gray," she added, with a small smile and a wave toward her hair.

The staff at Palolo is committed to doing whatever it takes to help the students, Higa said.

"The state test results alone cannot be the single indicator of the success of the school," she said. "The powers that be should come on the campus and see in the classrooms how hard the teachers work and how hard the students work. It's just that everybody learns at a different pace, because of our life experiences."

doe.k12.hi.us

State DOE: No Child Left Behind

doe.k12.hi.us/nclb/

U.S. DOE: No Child Left Behind

www.nochildleftbehind.gov

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]