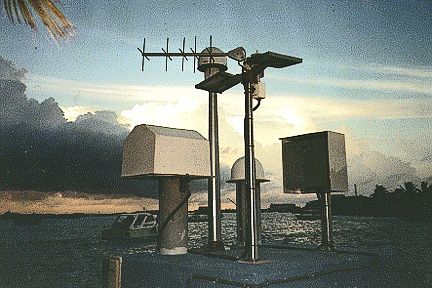

This tide station at Male, the Maldives, in the Indian Ocean on Dec. 26 showed sea level rising by up to 4 feet 8 inches.

Isle scientists work to

expand tsunami alerts

Warnings about large earthquakes

will be sent to Indian Ocean nations

that agree to plug in

Hawaii scientists and officials associated with the tsunami warning system are working with other countries and international organizations in efforts to expand the system to the Indian Ocean.

Since the disastrous Dec. 26 tsunamis in the Indian Ocean, "so many countries have jumped on the bandwagon," said Delores Clark, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration spokeswoman. "They want tsunami warning centers."

Clark said the scientists are providing technical assistance to countries that request it and are describing the American warning system. They point out that an effective system not only includes technology for detection, but public education, dissemination of warnings and evacuation programs, she said.

Until the tsunami network is expanded, the Japan and Pacific Tsunami Warning Centers have agreed to send bulletins on large earthquakes to countries that provide electronic circuitry to hook into, Clark said.

"They still won't get tsunami information because they're not hooked up to tide stations," she said. But if they know a strong earthquake has occurred, they can prepare for a possible local tsunami, she said.

Data is available "fairly quickly" from 11 tide gauges operated by the UH Sea Level Center in the Indian Ocean, said center Director Mark Merrifield. They automatically transmit in real time by satellite.

However, they were not much use for warnings of the recent tsunamis because they are in the central and western parts of the Indian Ocean, and the 9.0-magnitude earthquake was in the eastern ocean, he said.

Also, the gauges are not part of any tsunami warning system, he said. "There is no formal mechanism to evaluate the data for the Indian Ocean and, even so, no system to respond."

"Now there is great hope that's going to be reversed," said University of Hawaii oceanographer Bernard Kilonsky, with the Joint Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Research (JIMAR).

Attending an international meeting for development of a "tsunami warning and mitigation system" in the Indian Ocean March 3-8 in Paris will be Kilonsky; Charles "Chip" McCreery, geophysicist-in-charge of the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center at Ewa Beach; and Laura Kong, International Tsunami Information Center director.

They attended the U.N. World Conference on Disaster Reduction in Kobe, Japan, and have been going to other international meetings on tsunamis. Kilonsky noted recommendations at the Kobe meeting to establish an Indian Ocean Tsunami Warning Center as quickly as possible.

The UH operates the Sea Level Center with NOAA on the Manoa campus. The gauges are part of the Global Sea Level Observing System, which Merrifield also chairs.

The global observing system of 40 or 50 tide gauges grew out of a program to monitor sea level rise developed by UH professor emeritus Klaus Wyrtki, an oceanographer who pioneered understanding and forecasting of El Nino systems.

Thomas Schroeder, UH meteorology chairman and JIMAR director, said the technology in the tide gauges "is not dramatic news."

But real-time information from the instruments makes them valuable for many purposes, he said, from sea level variations associated with El Nino to hourly fluctuations associated with tsunamis. Most of the gauges are part of a tsunami warning system.

They are "the root element of the climate-observing network," Schroeder said. "They provide a lot of bang for the buck."

They are scattered throughout the Pacific in lagoons, bays and harbors, but it has been difficult historically to locate them in Indonesia and India, mostly for political reasons, Merrifield said.

He and other scientists involved with the tide gauge network issued a report Jan. 26 on Indian Ocean tsunami observations to assess the needs for future warnings.

Most stations transmitted data hourly, and had there been a warning system for the Indian Ocean, they said, confirmation of the tsunami at the Cocos Islands could have provided advance warning to the Maldives and other islands farther west.

"Similar transmitting stations in Thailand and Indonesia would have significantly increased the warning time for much of the Indian Ocean," they reported.

Merrifield said the wave took about three hours to reach Sri Lanka, about 3 1/2 hours to reach the Maldives, 7 1/2 hours to reach the Seychelles and about nine hours to reach the coast of Africa.

Water level dramatically increased at Male atoll in the Maldives, the measurements showed. The first and largest wave was 4 feet 8 inches high. "The Maldives are so low, it was devastating," Merrifield said. "It went over the top of the island."

At Sri Lanka and other sites west of the earthquake, Merrifield said, the wave rolled in as a crest with heights up to 7 or more feet.

East of the earthquake at Indonesian stations such as Sibolga, the tsunami first appeared with the sea level dropping, then rising. The water kept going up and down for three days at some sites, Merrifield said.

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]