This Japanese ema, to be offered at a Buddhist temple, represents a supplicant's vow to give up sake for three years.

Exhibit celebrates

the grain that binds

Asia

ONE DAY, when I was a child, I watched my mother refill our empty rice container. She hefted the huge 25-pound bag of Hinode and carefully poured. When the container was full, she set the bag upright, careful not to spill any stray grains, rolled the top of the bag closed and set it on the kitchen floor against a wall.

'The Art of Rice'"Spirit and Sustenance in Asia":On view: Through April 21 Place: Honolulu Academy of Arts Hours: 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Tuesdays to Saturdays and 1 to 5 p.m. Sundays Admission: $7 general; $4 seniors, students, military; children free Call: 532-8700

|

"No, no, NO! GET UP! Never, ever sit on rice!" she shrilled. "You want bachi?"

I didn't understand what the big deal was, so Mom explained that food in general, but rice above all else, was to be treated respectfully.

"My mother said if you sat on rice, your okole would turn red," she said gravely.

Yikes. Did my mother's bottom turn red? Would mine? Would it hurt?

"Never mind," she said. "Just don't sit on the rice. You don't do that to rice. Ever."

Such reverence for the globe's most popular staple is, in a nutshell, what the newest art show at the Honolulu Academy of Arts is all about. "The Art of Rice: Spirit and Sustenance in Asia," a traveling exhibit from the UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History, explores how rice has become entwined with identity, culture and artistic expression in Asia.

THE COUNTRIES that comprise Asia are nothing if not diverse, in politics, geography, culture and religion, to name a few things. "Nothing makes the area a sensible unit," says Roy W. Hamilton, curator of "The Art of Rice."

Except one thing. Rice.

"The 'rice belt' -- from India and Sri Lanka to China, Korea and Japan, and southeast to Indonesia through the Philippines -- 'Asia' is shorthand for that area," Hamilton says. "The important point is that rice, more than any one single thing, holds Asia together."

Rice is believed to have been domesticated 8,000 years ago in China, although some research proposes that it might actually be 15,000 years ago in Korea.

"Rice predates even religion," says Hamilton. "And yet, rice is a religious idea, too."

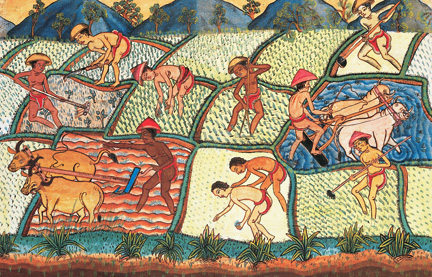

A painting on cloth, 1930s, of Balinese rice farmers.

Ultimately, rice itself is elevated to the sacred and divine. The life cycle and fertility of plants are equated with the life cycle and fertility of the goddess and of humankind. The idea that human fecundity is related to that of a rice crop isn't far-fetched, Hamilton points out. "It's literally true. In subsistence economies, where the seeds for the rice crops were inherited from ancestors, rice could not exist without humans, and vice versa."

Imbued with such sanctity, "rice can nourish a human being the way no other food can," Hamilton says. "The growing and eating of rice is seen as defining what it means to be human."

Rice has been part of all facets of life in Asian subsistence-farming communities, from birth, death, daily and annual rituals to everyday existence.

"People feel surrounded by rice their entire lives, and it becomes part of their personal identities," Hamilton says.

In many cultures rice is the first food fed to babies. Rice and rice wines turn up during engagement and wedding celebrations. And rice urns are among provisions for the afterlife.

Asian cultures hold rice festivals based on crop cycles and celebrating the virtues of rice. Some mark the passage of time through the cycles, characterizing months according to the activity in the rice fields.

Rice has even served a moral function.

A scroll from the Imperial Palace in 18th-century China, for instance, depicts a series of 23 illustrations of the rice agricultural cycle.

"Every new emperor of the Ching dynasty republished the prints," says Hamilton. "China (then) was a Confucian state, and the prints chronicled a logically ordered series of steps to produce rice. This order paralleled Confucian society, which the emperor sat at the top of."

"Mr. Rhu in Eunhang Dong," 1991, an acrylic on paper by Jonggu Lee of Korea.

The show includes not just traditional forms of art, but adorned tools, items made of straw, posters and calendars from popular culture, and festival videos. Unlike many art museums that consider "real art" to be limited to painting and sculpture, Hamilton said Fowler has an inclusive view of art.

"We're a museum of cultural history, and we give all the items equal weight. Some items are tools, others are things made of straw, but they're beautiful. And they can tell as much about a culture as a painting or a sculpture can."

Hamilton says each stop of the exhibit required a different rotation of works because some of the pieces were too fragile to take on the road. Honolulu's show includes shadow puppets, sake bottles, textiles, Zen paintings, popular festival works and some prints from the academy's own collection.

Rice is presented to the goddess Shiva, 2003, in a work made of clay, wood, cloth and other materials, by Gourishankar Bandophadaya of India.

This rice was shorter in grain to make it less susceptible to weather damage, matured more quickly than traditional varieties and bore a heavier load of grain, which made up a greater proportion of the plant's weight.

Along with similar changes to wheat and corn, high-yield rice launched what became known as the "green revolution." The revolution employed fertilizers and pesticides that enabled growers to double or triple crops in a year.

Matters progressed rapidly. By 1974 in Bali, 48 percent of rice fields were planted with the new varieties; by 1977, Bali's rice crops were 70 percent high-yield. The war on famine was successful -- but not without cost.

The high-yield rice proved to be vulnerable to insects. Fertilizers and pesticides damaged fields and caused health problems. While poor conditions made it difficult to grow the modern varieties, government policies made traditional varieties inaccessible.

"Many of the poor resorted to subsisting on millet," Hamilton says in "The Art of Rice."

Commoditization of rice also leaves some segments of many societies without a means to earn a share of the crop.

Hamilton discusses one such dilemma in Java in his book: "The traditional Javanese form of harvest ... was open to all. By simply showing up at a field where the harvest was taking place, and joining in the work, both men and women could earn a small portion of what they reaped in return for their labor. This system provided a crucial safety net for the landless and the poor. ...

"(With commoditization), the labor is organized by agents under contract with the landowner. The workers are mostly male and are paid a cash wage rather than a share of the crop. ... The losers, of course, are those who are no longer involved: the poorest and weakest ... who have lost their right to claim a share of the crop by showing up to work."

Another price of the shift away from subsistence farming is rejection by younger generations of cultural practices such as rice festivals and homages to a rice deity. And as modernization evolves and youth are educated, there is a generational move away from rice farming.

These trends are surely disheartening. And yet ... in this corner of the world, local youths go away to college each year with rice pots tucked in their luggage. Even folks crossing the ocean for a week at Disneyland take their pots along. "I just can't live without my rice," they say.

When the green revolution was in full swing, my kid sister was having a love affair with rice. "It's my favorite food," she would say.

Once she even tried combining it with her other favorite food, bubble gum. "Rice goes with everything, right?" she said as she chewed away.

No matter that the combo didn't stick. She'd still flex her muscles and pose for us. "See my muscles?" she would brag. "Rice makes me strong."

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]