Relics like these, said to be linked to the death of Jesus Christ, will be part of the "Relics of the Passion of the Lord Tour," which will open here next week. The items will be displayed at Catholic churches on four islands.

Relics roadshow

Artifacts said to be linked to Christ’s

death will tour the state as Christians

begin observing Lent

A display of artifacts said to be linked to the death of Jesus Christ will open here next week in the "Relics of the Passion of the Lord Tour."

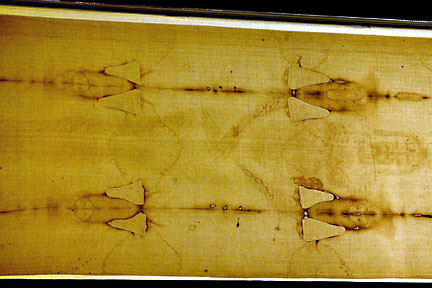

Sponsors of the traveling show say the relics include tiny pieces from the cross on which Jesus died and the crown of thorns placed on his head by his Roman executioners. The exhibition will also include reproductions of two ancient cloths, the Shroud of Turin and the Veil of Veronica, which purportedly show the likeness of Christ's face.

Display sites for touring relicsThere will be a Mass or prayer service at each church to open the relic display for the "Relics of the Passion of the Lord Tour":» Wednesday -- St. Patrick Church, 1124 7th Ave., Kaimuki, 8 a.m. and 7 p.m. » Thursday -- St. John Apostle & Evangelist Church, 95-370 Kuahelani Ave., Mililani, 7 p.m. » Friday -- Our Lady of Good Counsel Church, 1525 Waimano Home Road, Pearl City, 7 p.m. » Next Saturday -- Star of the Sea Church, 4470 Aliiko St., Kahala, 7:30 a.m. » Next Saturday -- St. Anthony Church, 148-A Makawao St., Kailua, 1:30 p.m. » Feb. 13 -- St. Augustine Church, 130 Ohua Ave., Waikiki, 10 a.m. » Feb. 13 -- Holy Rosary Church, Paia, Maui, 5:30 p.m. » Feb. 14 -- Holy Cross Church, Kalaheo, Kauai, 6 p.m. » Feb. 15 -- St. Joseph Church, Hilo, Hawaii, 6:30 p.m. » Feb. 16 -- Co-Cathedral of St. Theresa, 712 N. School St., Liliha, 6 p.m.

|

"The bulk of these relics of the Passion have been preserved since the fourth century in the Basilica of Santa Croce in Rome," said Andrew Walther, vice president of the Apostolate for Holy Relics, based in Los Angeles. According to church history, the mother of Rome's first Christian emperor brought relics back from Jerusalem after a pilgrimage in 318 A.D. He said major portions of the artifacts, including a large beam from the cross, remain at the basilica that Emperor Constantine and his mother, Helena, built.

"There is an unbroken chain of reverence to these very things; the Christian world is making pilgrimages to these very things," Walther said.

The tradition of honoring relics, such as the bones or possessions of saints, has been observed for centuries, Walther said: "Relics are important reminders to believers of those people who have gone before us and who have done things correctly in their lives.

"In the case of the Passion relics, they are reminders of our redemption. When people come and see them, they have more of a connection to the events. There is a lot of interest in the final days of Jesus and his sacrifice for people," Walther said.

The Catholic Church teaches that relics of saints may be venerated, but it does not authenticate artifacts. The sponsoring groups are not official arms of the church. They were organized by lay members of the church.

This display recalling the suffering and death of Christ is timely because Christians are beginning the observance of Lent, said the Rev. Antonio Rosario, associate pastor of the Co-Cathedral of St. Theresa.

"It is a visual thing for the faithful, to remind us of what Christ did for us." Rosario said he will use the theme of the passion in his homily when the display opens at the parish. "I will focus on the penitential aspects, of making our life to be more Christlike."

Walther acknowledged that there are skeptics, including some Catholics, who question the provenance of slivers allegedly dating back to Christ's death in about A.D. 30.

"These are relics I am comfortable with," he said. "I have a master's degree in ancient history. People are open to accepting secular relics. No one wonders if King Tut is King Tut.

"The key thing the church teaches about relics is that it is a question of faith. Believers won't find this a problem. For those who don't believe, they won't be happy with any explanation."

Walther said the relic show will be taken to Baltimore, Denver, Detroit, Milwaukee and Phoenix. Last year, it was shown in St. Louis and Washington, D.C.

Further information can be found at www.smcenter.org or www.apostolateforholyrelics.com.

Authentication of biblical

material often stirs debate

An ancient fortress, a burial box and a piece of cloth -- historical remains related to the Bible never cease to provoke heated debate, whether the discoveries are thought to be tantalizing clues, cynical hoaxes or just archaeological mistakes.

Right now, for instance, three highly technical disputes have erupted over materials linked to Scripture:

» In the most important development, scholars say tests on remains from a dig in modern-day Jordan indicate the biblical country of Edom existed during the era of Kings David and Solomon, if not earlier. The find could undercut skeptics of biblical history.

» Prosecutors in Israel filed fraud charges Dec. 29 involving a purported first-century inscription of Jesus' name. But this month, a prominent archaeology magazine will assail the government's scientific evidence.

» New testing indicates the Shroud of Turin, a celebrated relic said to be Jesus' burial cloth, could actually date from his time. That opposes scientists' earlier conclusion that the artifact is a fraud from the medieval era.

The unending popular interest in such matters is undeniable.

Says Niels Peter Lemche of the University of Copenhagen, part of an arch-skeptical faction that treats most of the Old Testament as politically motivated fiction: "The public -- that is, people not members of the fraternity of biblical scholars -- are still mainly interested in history. Did it happen as written or did it not happen? That is the question most often asked when talking to an audience of laypersons."

The public's fascination is evident to Lemche in the success of Biblical Archaeology Review, a 30-year-old glossy magazine with 120,000 subscribers. It explains scholars' ongoing dust-ups for lay readers.

Consider the excitement over the magazine's 2002 report about a first-century burial box for bones (or "ossuary") with an inscription that reads "James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus." James led the early church in Jerusalem and, depending on which Christian tradition is being invoked, was either Jesus' brother, stepbrother or cousin.

Some immediately suspected the inscription was a hoax perpetrated either in ancient or modern times. Israel's new fraud indictments say the ossuary's owner was among five men who forged dozens of biblical artifacts.

The magazine's editor, Hershel Shanks, says the issue being released Feb. 15 will argue that nobody can yet decide whether the inscription is fake because Israel has thoroughly "bungled" the scientific evidence.

Meanwhile, the important Edom research has added fuel to one of the hottest archaeological disputes of recent years.

The Shroud of Turin, the 14-foot-long linen strip revered by some as the burial cloth of Jesus, is pictured at the Cathedral of Turin, Italy.

But many scholars have claimed the Bible got it wrong, and no Edomite state existed before the eighth century. Part of their thinking stemmed from the fact that physical evidence of Edom was lacking. Meanwhile, Lemche's camp claimed that far-later writers invented David and Solomon and their kingdom, which the Bible says began around 1000 B.C.

Related to that, Tel Aviv University archaeologist Israel Finkelstein made a controversial bid to shift the usual dating of major sites in the Holy Land to say they came just after Solomon's reign. Unlike Lemche's group, Finkelstein doesn't deny there was a Solomon, but his theory means the Bible's record of Solomon is hugely distorted. The argument between Finkelstein and most archaeologists' older chronology was pursued in Science magazine and at a recent radiocarbon summit in Britain.

Now comes the report on Edom, in the current edition of the quarterly Antiquity, by Russell Adams of Canada's McMaster University, Thomas Levy of the University of California-San Diego and other colleagues.

They say pottery remains and radiocarbon work at a major copper processing plant in Jordan indicate settlement in the 11th century B.C. and probably before that, with a nearby monumental fortress from the 10th-century era of David and Solomon. They are convinced the site was part of the Edomite state.

University of Arizona archaeologist William Dever had been skeptical about Edom's existence that early but says this "discovery is revolutionary" and lends credibility to the biblical kingdom of David and Solomon.

The Shroud of Turin dispute also involves radiocarbon tests, those done in 1988 on threads from the famous relic -- which bears the faint image of a crucified man. The tests dated the cloth at 1260 to 1390 A.D. But in the current edition of the journal Thermochimica Acta, Raymond Rogers of Los Alamos National Laboratory argues that the tested threads came from later patches and might have been contaminated.

Rogers' major point is that his chemical tests found no vanillin, a compound in flax fibers that gradually disappears. From that he calculated that the shroud is 1,300 to 3,000 years old and could easily date from Jesus' era.

The cloth is "from the right time, but you're never going to find out if it was used on a person named Jesus" through science, Rogers notes.

Indeed, given the difficulties in interpreting the meaning of scattered items that by chance have survived from ancient times, the latest findings probably won't settle any of the three debates -- if any of them can ever be truly put to rest.

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]