The remains of Mother Marianne

Cope will be exhumed from their

resting place in Kalaupapa

|

Excavation begins tomorrow at the Kalaupapa grave of a nun who is on track to be named a saint for her work with leprosy patients.

Hawaii's ill called

|

Witnessing the excavation will be local Catholic officials and members of the Sisters of St. Francis who plan to take the bones to their Syracuse, N.Y., headquarters, where a shrine will be built to honor the nun. Cope left Syracuse with six other nuns in 1883, answering a call from the kingdom of Hawaii for help in the epidemic of leprosy with which more than 8,000 people were stricken.

Also watching the event are the last of the patients once quarantined in Kalaupapa, which is now a national historic park. Fewer than 30 still live there.

"She was a risk taker," said Sister Alicia Damien Lau, who manages a system of care homes on Oahu. "She was a practical woman; she was able to move mountains."

Like Lau, many modern nuns are inspired by Cope, who was a 45-year-old career woman, administering a hospital that taught medical students, before she took the challenge to help people who were made outcasts by disease.

"In those days when medicine was totally different, she was very conservative about how she took care of people," Lau said. "She said, 'none of my sisters will contract the disease.' They didn't. That's awesome."

"She came expecting to return home, but she made such a generous decision to stay, to keep listening to God's call," said Sister Marion Kikukawa, principal of St. Joseph School in Hilo and the vice postulator for the Cope sainthood cause that appears to be on a fast track.

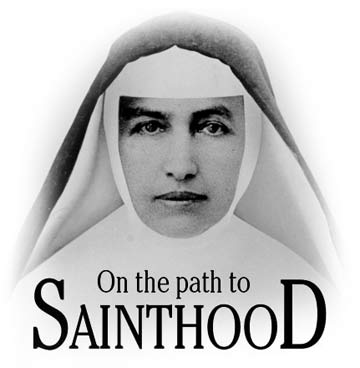

A Vatican panel of cardinals and bishops voted a year ago that Cope demonstrated "heroic virtue" in ministering to patients at Kalaupapa and merited the title "venerable." That was step one in the sainthood process, and last month Pope John Paul II announced the second step is secure: she will be declared "blessed" in a ceremony later this year.

Kikukawa said Cope's life was a demonstration of "how unselfishness and attentiveness to the call God extends to us day after day can result in many good results happening. As her story spreads, people will come to recognize that God calls us more in our day-to-day actions rather than what may be considered the big heroic response."

That, in a nutshell, is why the Catholic Church identifies people as saints.

"Teenagers have idols, all of us could use idols who have led exemplary lives," said the Rev. Joseph Grimaldi, judicial vicar of the Honolulu diocese. "Pope John Paul II has found a way to hold up models of every kind."

Mother Marianne Cope, in wheelchair above, with Sisters M. Algina Sluder, M. Benedicta Rodenmacher, M. Leopoldina Burns and Adelaide Bolster, a patient and a teacher, were at Bishop Home on Aug. 1, 1918.

He said the church requires that, at this point in the sainthood process, the body be exhumed and the remains be sealed in a zinc container. A local tribunal is required to witness the procedure and document the identification of the body and the collection of bones and other artifacts that may be found, such as fragments of clothing, rosary or cross. On the tribunal with Grimaldi are diocesan chancellor John Ringrose and the Rev. Joseph Hendriks, pastor of St. Francis parish in Kalaupapa.

The actual digging will be "standard archaeologic procedure," with each shovelful sifted through a screen so that not a sliver is missed, said Vincent Sava, a forensic archaeologist with the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command Central Identification Laboratory in Honolulu. Sava, a Catholic, will lead a team of four of his co-workers and a fifth archaeologist. They are all volunteers.

Sava doesn't expect the venture to be difficult. His preliminary probe did not detect a vault. He expects to be able to make a "biological profile" from the bones, identifying the sex, race and age of the person buried. A room in the nearby Bishop Home convent will be used as a makeshift laboratory, but a fuller examination will be done when the bones are brought to an Oahu mortuary before the container is soldered shut.

"It's relatively rare to be part of exhuming an historical figure," said Sava. "When President Zachary Taylor was exhumed recently it was quite an event in my profession."

As for being a Catholic handling bones of a saint? "We are so focused on the mission, it's hard to think about anything beyond forensic procedure," said Sava.

Some 20 Franciscan sisters are in Kalaupapa, including leaders from the Syracuse headquarters. They include Sister Patricia Burkhart, general minister of the religious order, and Sister Mary Laurence Hanley, who has headed the Cope sainthood cause since 1983. With the late Hawaii author O.A. "Ozzie" Bushnell, Hanley co-authored "The Song of Pilgrimage and Exile," a 1983 biography of Mother Marianne.

Mother Marianne Cope, right, arrived with the first Franciscan nurses in 1883. Walter Murray Gibson, prime minister for King Kalakaua, was in the background.

"I pray every day that she will be made a saint in my lifetime," said Toal, 87, a New Jersey native, who was inspired to join the order because of the story of Cope. But she dissented from the popular view among her sisters to move the bones.

"I voted no," said Toal. "I said she belongs here, she gave her life here."

Bernard Punikaia, 74, who was sent to Kalaupapa when he was 16, also said "this thing upsets me. To take it away doesn't respect the wishes of the people. For us, Damien and Mother Marianne were part of the family." Punikaia, who has been recognized by state lawmakers as an outspoken activist for patients' rights, visits Kalaupapa occasionally but is required by medical problems to stay on Oahu most of the time.

Kalaupapa pastor Hendriks said "Mother Marianne was a humble lady; she would say, 'leave me alone.'

"But it was decided a long time ago (to move the remains)," said the priest. "Her life is more important, the honor to be beatified. When one of the family is honored, it is an honor to the whole family."

Henry Nalaielua, 79, who was sent to Kalaupapa in 1941, recalled that the "same thing happened to Father Damien. The king of Belgium claimed his bones in 1936.

"I think it's a good thing for the sisters," he said. "They don't want her to be alone. Kalaupapa won't be the place for her after the sisters abandon the place."

Franciscan sisters have been in service as nurses and teachers in Hawaii since Cope's arrival. In 1927, the order opened St. Francis Hospital in Honolulu.

Of the 50 Franciscans now in Hawaii, two still work in Kalaupapa. Sister Frances Therese Souza is on the nursing staff there and Sister Frances Cabrini Morishige, a retired nurse, works as a volunteer.

Reflecting on the dwindling population of elderly patients, Nalaielua said, "In Kalaupapa now, it's not so much seeing who you know there, it's remembering those who aren't there anymore."

Isles have handle

on leprosy

There are more former leprosy patients living in Hawaii today than the total number of people sent to Kalaupapa during 100 years of forced isolation.

A 2002 state Department of Health census counted about 10,000 people diagnosed with Hansen's disease here.

"There are 20 to 25 new cases each year, mostly migrants from South Pacific islands," said Michael Maruyama, branch chief of the Department of Health Hansen's Disease program.

The very name of the disease carried a stigma for centuries. It is now officially called by the name of the Norwegian physician, Gerhard Hansen, who first identified the bacillus that causes it.

About 40 former patients who contracted the disease before drugs were developed to treat it are still alive. Their average age is 76 and the state is committed to providing them lifelong care. Some still make Kalaupapa their home, and others live on Oahu. They are among nearly 8,000 people who lived there before the quarantine was lifted in 1969.

Now, patients undergo multiple drug therapy for six months to a year. "Once treated, they are considered cured," Maruyama said.

Physicians are required to report cases of the infectious disease. There is no state treatment facility for new cases. The state collaborates with private doctors "so it does not disrupt a patient's life," he said. The Health Department provides help with case management, education and follow-up to be sure patients complete treatment.

Before the medication was developed, the disease could cause disfigurement and disabilities. "In this day and age, if we are doing our job, there shouldn't be any recognizable sign," Maruyama said.

www.state.hi.us/health/

[News] [Business] [Features] [Sports] [Editorial] [Do It Electric!]

[Classified Ads] [Search] [Subscribe] [Info] [Letter to Editor]

[Feedback]