MAKAI ]

MAKAI ]

At Iolani Palace in 1998, a Hawaiian man wears a traditional malo during a protest of the annexation of Hawaii to the United States in 1898. The portrait of Kamehameha II, draped in maile leaves, expresses the promise of the continuity of a Native nation.

Children of the land

A new photo book documents

the ways of life lost in the

development of Hawaii

It could just as easily have been Adolf Hitler or Mao Tse-tung, but Josef Stalin is the one most often credited with saying that while killing a single person is murder, killing millions is just a statistic. Put faces to those "statistics," however, and the humanity of those anonymous victims is restored. That's what the Cambodians are doing with the photos on display at the memorials to the victims of communist genocide there. That's what Ed Greevy and Haunani-Kay Trask are doing with "Ku'e," a coffee-table-size photo book documenting the history of contemporary land struggles in Hawaii.

"Ku'e," by Ed Greevy and Haunani-Kay Trask (Mutual Publishing, $36.95, 128 pages) Book signing: 6 to 9 p.m. Friday, Native Books Downtown

|

Greevy's involvement with local community issues here started with Save Our Surf, a group formed to preserve surf sites and protest shoreline developments. As SOS joined other groups in the larger struggle to preserve traditional local lifestyles, Greevy used his camera to document their combined efforts to protest and prevent the eviction of Hawaii residents of all ethnicities from their farms, taro patches, fishing villages and urban communities.

Greevy met Trask at a meeting of the Protect Kaho'olawe 'Ohana in 1977 and they've been friends ever since.

The 83 photos from his archives illustrate the struggle against evictions in Kalama Valley, Waiahole/Waikane, Chinatown, Sand Island, Makauea and Heeia Kea, as well as related campaigns to end the bombing of Kahoolawe and prevent the building of the H-3 through culturally significant sites in Halawa Valley.

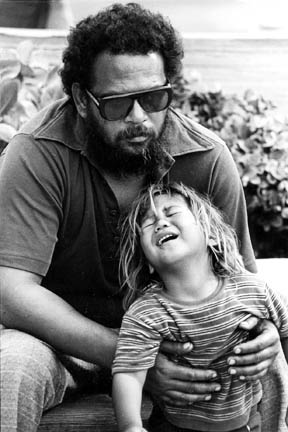

In 1980, the state arrested dozens of Sand Island residents and their supporters during an eviction battle that pitted the city and state against residents. After the arrests, some of the residents, including this father and child, took their story to Waikiki, where they shared their plight with isle visitors. The residents eventually lost the battle and their homes were bulldozed away.

There is, after all, no question that a growing population needs homes, or that hotels, strip malls and industrial parks provide jobs for more people than farms and taro patches.

Greevy's portraits show that the victims were of many ethnicities and cultural backgrounds. These weren't drifters and derelicts who were homeless by choice or as the result of substance abuse, but folks who had spent their lives as plantation laborers or working the land or sea in the old Hawaiian style.

Greevy and Trask note that the activists occasionally won one. Waiahole/Waikane remained rural after the government agreed to buy the land and allow the old-time residents to stay on. The bombing of Kahoolawe eventually ended. And the American government did eventually issue a pro forma apology for the involvement of American officials in the overthrow of the legitimate Hawaiian government in 1893.

In the larger scheme, however, most of the people and almost all the places seen in Greevy's photos are long gone.

And so, Hawaii residents who live in homes built on lands where people once raised pigs or farmed, who find it convenient to use the H-3, or who benefit from the way things are in 2004, will find in "Ku'e" a reminder of what it cost to create the Hawaii we now enjoy.

The military bombing of Makua Valley has been a decades-long cause of Hawaiian activists that remains unresolved today. In 1977, this child joined the protest.

In 1975, resident Billy Molale left a burning house on Mokauea Island, an islet near Sand Island. The fire, set by the state, was intended to evict residents who had created a housing village there.

When members of Protect Kahoolawe Ohana landed on the island to protest bombing there, they were arrested and faced Federal court trials. During the trials, as on this day in 1977, Ohana members showed up in native dress at the courthouse in support of their peers.

Click for online

calendars and events.