|

Isle high-tech

companies profit

from 9/11-driven

security market

On a rooftop at the Hilton Hawaiian Village yesterday, Trex Hawaii senior scientist Chris Martin played the role of a suicide bomber, strapping mock pipe bombs to his body and cloaking them under a heavy tunic.

But he was no match for a high-tech sensor 15 feet away, which used proprietary Trex Hawaii technology to reveal the ruse on a nearby computer screen.

"This does infrared one better because it can see through clothes. In fact, it can see through plastic and even some walls," Martin enthused.

It is also one of several high-tech products on display at Waikiki's 2004 Asia-Pacific Homeland Security Summit whose creators hope to find a big new market in the war on terror and the push for homeland security.

The Trex Hawaii sensor is a retooled version of a low-wavelength sensor technology originally developed to help military aircraft land in poor weather. But the company sees a future in thwarting suicide bombings in Iraq and other applications.

"What's happening is fascinating," Trex Hawaii President Al Hunter said. "We have a lot of technology developed for different things that we can now adapt to homeland security and make it effective without much extra effort."

Before "homeland security" gained household-word status and its own Cabinet agency, its technology providers toiled in relative obscurity for a niche market.

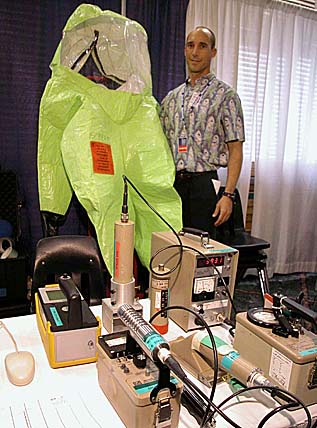

"In the past you had one agency off in a dark corner, making policy," said Tim Myhri, national sales manager for Nor E First Response Inc., a maker of portable decontamination units.

But the sudden prioritization of security has created a deep-pocketed new technology customer in the Department of Homeland Security that has only begun to start shopping for new gadgets.

"When you talk about growth industries, this is one of the biggest right now, and it's just getting started," said Nelson Kanemoto, president of Referentia. His Honolulu-based company is a prime example of the potential that an emerging homeland security market holds for some firms.

A graduate of Roosevelt High School and the University of Hawaii's computer science department, Kanemoto founded the company in 1996 as a provider of interactive training products for software companies.

But Referentia has since branched into futuristic computer technology now used by Marine Corps battle planners who simulate variables as intangible as fear and loyalty using complex algorithms to come up with millions of po-tential battle outcomes, all generated by the Maui Supercomputer.

"It looks at what happens when things go wrong for one side or the other. What happens when fear sets in? Usually, when fear goes up, accuracy goes down," says Larry Lieberman, the company's business development manager.

Kanemoto sees myriad homeland security applications for the technology. In crowd control, for example, the attributes and mind-set of a particular crowd such as a young concert audience can be simulated to learn how a mob will react to an emergency.

Referentia is in talks with the Homeland Security Department to provide some of its technology for the department's Critical Infrastructure Protection Group.

Other products raise the role of computers in life-or-death decisions to an alarming level.

21CSI, an Omaha, Neb.-based firm that recently opened a branch office at the Manoa Innovation Center, has a software application that approximates human decision-making by crunching huge amounts of information. Information can be submitted remotely in real time by soldiers or security personnel, after which the computer recommends a course of action based on "what a human would do," said company President Jeff Hicks.

Hicks demonstrated by simulating data showing an unidentified fishing vessel coming a little too close to a simulated Navy ship.

The computer's snap judgment: "The fishing vessel must be destroyed."

"9/11 demonstrated that we needed to have the capability to make decisions fast," said Hicks, who remembers watching helplessly as the attacks unfolded while he was a staffer at the U.S. Strategic Command.

"In a case like that, there is too much information out there for a human to consider and make a decision."

The company is marketing the product to civic authorities who could need help deciding on a course of action in an emergency. The message is apparently getting out. Hicks said revenue has doubled every year since 21CSI's founding in 1996, and he projects 2005 revenues of $15 million.

Technology firms already have benefited since 2001 as Department of Homeland Security funds have trickled down to cover immediate needs such as security for military bases, key landmarks and installations, and to local governments keen on protecting utilities sites.

But with many of those bases covered, said Referentia's Kanemoto, homeland security money will soon start sloshing over into the private sector, and Hawaii companies are well placed to reap the benefits.

"You've got a lot of operational (military) commands here and a unique environment for homeland security due to the importance of the ports," he said, noting that Homeland Security Secretary Tom Ridge's address yesterday at the summit stressed the need for greater port security.

But the good times come with some guilt as well.

"It's a double-edged sword," said Patrick O'Brien, president of Aiea-based Security Resources, a maker of wireless security and monitoring systems.

"Our local business has tripled since 9/11, but it's unfortunate that it comes at the cost of such a catastrophic event."

www.hlssummit.hawaii.gov/