OAHU'S NEXT LANDFILL

With a Dec. 1 deadline looming,

a Council panel is still divided

over a new disposal site

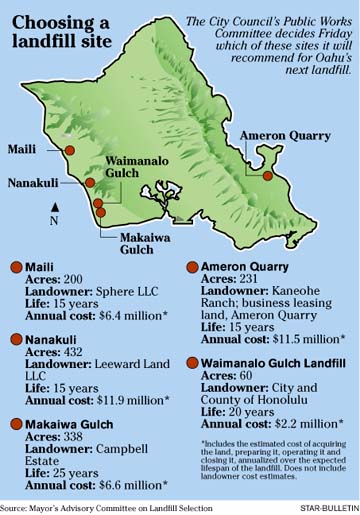

As the City Council nears its decision on where to put Oahu's next landfill, most members won't say which of five proposed sites they favor or disfavor.

Oahu solid-waste

» 1.6 million tons a year generated. |

"None of the above," says the outgoing councilman for the Leeward Coast, the area that contains four of the five sites: Makaiwa Gulch, Maili, Nanakuli and an expansion of the existing landfill at Waimanalo Gulch.

Gabbard said he is just as opposed to putting a landfill at Kapaa Quarry in Kailua, he says.

Instead, he's a proponent of shipping some or all of Oahu's trash to a large mainland landfill, then reducing those shipments as much as possible with more recycling and technology.

But Gabbard, who leaves office this year, apparently stands alone. Other councilmembers seem convinced that an islandwide landfill is necessary -- though they also say they want the city to increase recycling and embrace new waste-disposal methods to extend the landfill's life.

"I don't see how we can get away from it (having a landfill)," said Council Chairman Donovan Dela Cruz. "When you look at other counties, states or countries, I'm not sure how many have totally removed themselves from using or having a landfill site."

At minimum, Dela Cruz said, a site must be permitted and available to deal with debris from hurricanes or other natural disasters.

"We're just going to have to make a decision," Councilwoman Ann Kobayashi said. "That's what we 'get paid the big bucks' to do, so we're going to have to do it. We should do it without emotion.

"And whatever site we choose, there should be some kind of financial benefit for that community," she added.

Other councilmembers and Mayor-elect Mufi Hannemann have expressed support for some kind of compensation -- such as parks or roadways -- for the community that gets the landfill.

The Public Works Committee has sat through hours of testimony this year from companies that promise a better way for Oahu to get rid of trash: shrinkwrap it in compressed bales and ship it by barge to a mainland landfill. Melt it at high heat, ending up with inert pellets or a glassy substance. Shred it, to reduce the "airspace" needed in a landfill. Compost it and eliminate harmful components through controlled chemical reactions.

Some of these alternate technologies are being used in other states or countries. Some exist on the drawing board or in incubator stages.

Other proposals are more familiar: expand the reliably performing HPOWER waste-to-energy plant. Recycle more glass, plastic, metal, tires and green waste.

The city has made no commitment to any of the technologies, and with a new mayor coming in January, those decisions remain ahead.

"Technology, recycling, shipping waste out -- they're all factors" in dealing with Oahu's garbage, says Public Works Committee Chairman Rod Tam. But Friday's meeting is solely to select a landfill site.

Joe Hernandez, left, gave Kaimuki High School students a tour of the Waimanalo Gulch landfill Friday. The students took field trips to various waste-disposal sites. Part of the group were Debra Chong-Gum, left, Krea Branco, Nikcole Sugasawara, Jade Verdadero, May Cabong and Sarah Shinohara.

The decision is a tough one, so even how the decision is made becomes a political football. Two hearings on where to put the landfill in March attracted more than 200 people each night, most protesting the idea of a landfill in their community.

Councilman Charles Djou worries that with five finalist sites and five members, the committee could talk all day and not reach a consensus.

Djou said he will suggest Friday that committee members rank their choices, then have a city clerk total the scores and make the high point-getter the site recommended to the full council.

"It's not secret. This is the way they select national championship teams with the Associated Press," Djou said.

Tam said he opposes Djou's method. Tam said he will ask the committee to follow its normal procedure: One member will make a motion to choose a site, another seconds it, there's discussion and a vote.

"We've got to follow Robert's rules of order," Tam said. Djou's idea "hasn't been tried," he added. "It's not tested. With this emotional issue, do we want to take a chance of testing it?"

A bulldozer pushed waste material into the Waimanalo Gulch landfill Friday.

All but Waimanalo Gulch, site of the current landfill, were recommended by the panel. However, four members then quit in protest, saying it was irresponsible not to include the lowest-cost alternative.

Based on that argument -- and questions about whether the advisory panel violated the Open Meetings Law in making its decision -- Tam's committee put Waimanalo Gulch back on the list.

Mayor Jeremy Harris and other city officials had promised Leeward Coast residents and the Land Use Commission that Waimanalo Gulch will be closed in 2008, even though they say it has the potential to be expanded and used for another 20 years.

Todd Apo, the incoming Leeward Coast councilman and an employee of Ko Olina Resort, opposes putting a landfill in his district. Ko Olina and many Leeward residents have been vocal opponents of keeping the landfill where it is.

One thing the advisory panel didn't calculate was the potential economic cost to landowners if the city took their land for a landfill.

Campbell Estate has plans to build a community of up to 4,200 resort and residential homes at its Makaiwa Hills and Kapolei West holdings, says Steve MacMillan, Campbell's chief executive.

In a March 29 letter to the city, MacMillan said his firm stands to lose at least $108 million if a landfill goes on its Makaiwa Gulch land and that it would fight city condemnation attempts in court. The estate claims that it would have to abandon or postpone development plans.

Ameron's rock quarry at Kapaa is one of only two on Oahu. The company said in letters to the city that the city's estimated cost to acquire the land is less than one-tenth of its value and doesn't include relocation costs for its business, lost profits and increased costs. The company said the city underestimated costs to manage a landfill at Kapaa and to close it and projects the cost to the city of putting a landfill there would be $186 million.

A key point that drives up the cost of a landfill at Kapaa is the higher rainfall there -- about 88 inches a year -- compared to the Leeward sites, which receive about 22 inches.

To prove his point, Ameron President Wade Wakayama likes to show photos of the quarry pit filled with water after heavy rains last winter. More rain at a landfill means increased maintenance costs to keep pollutants from escaping in runoff.

Meanwhile, the owners of the Nanakuli site, Leeward Land LLC, informed Tam's committee on Oct. 22 that they would be happy to have a landfill on their site. But they want to run it themselves and have the city pay to dump garbage there.

"They would object to the condemnation" if the city chose the site and wanted to run the landfill, Tam said. "I'm quite sure they would embroil us in a lawsuit."

Leeward Land LLC spokesman Greg Apa said his company has been doing preliminary site work on the land for a year and intends to develop it as a municipal landfill whether or not the city contracts to use its services.

However it's done, "we gotta make a decision," Tam said. "The last Council meeting of whole year is Dec. 1 and we promised the Land Use Commission that we will have a site identified."