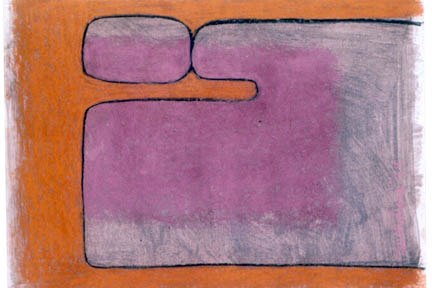

Harry Tsuchidana's "Sprouting" is a Casein painting from 1971.

Creative expression flows

constantly for Salt Lake

artist

Ask artist Harry Tsuchidana a question and you'll get an answer. It will be interesting, most likely anecdotal and engaging. But if you're looking for a straight answer, you're out of luck. Maybe one out of a hundred will be like that. Tsuchidana responds to questions in the same way he experiences life: in a stream of consciousness.

"Inner Scapes"An abstract painting and sculpture exhibitionWhere: Hawaii State Art Museum, 250 Hotel St. (the old Armed Forces YMCA) When: Through Feb. 27 Hours: 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays to Saturdays through Feb. 27; closed holidays Admission: Free Call: 586-0900

|

Like Superman, Tsuchidana's mind travels faster than a speeding bullet, across his 72 years, from his childhood in Waipahu to his early adulthood on the East Coast, and back to today, where several of his pastels are on display at the Hawaii State Art Museum in an exhibition titled "Inner Scapes." His works stand alongside those of 38 other local abstract artists, including Satoru Abe, Isami Doi, Tadashi Sato and Reuben Tam, who are among Tsuchidana's contemporaries and friends.

TSUCHIDANA'S CROWD is a lofty one in the local art world, credited with bringing the abstract movement to Hawaii in the 1960s. Tsuchidana arrived in New York in 1956. He met Abe on his first day at the Whitney Museum of American Art, and soon he built friendships with Tetsuo Ochikubo and Jerry Okimoto.

"Satoru lived in the same building as me on the fifth floor," he says. "I was on the fourth floor, and Isami Doi was on the third floor.

"I met my wife, Violet, through Isami. My wife's sister used to go with their son," Tsuchidana recalls. "Isami's wife taught me in grade school. She failed me twice."

When Tsuchidana married Violet, Sato was his best man. Tsuchidana still welcomes some of the New York gang to his home to drink and socialize.

"They were almost like the brothers I never had," he says.

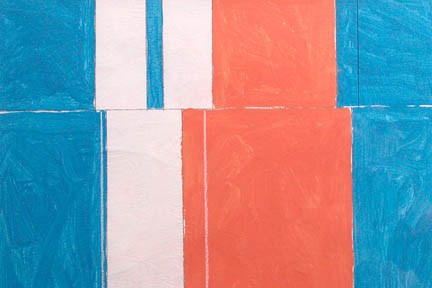

"View from the Train" is a tempera triptych piece that Harry Tsuchidana created in 1976. Tsuchidana also works in acrylic, watercolor and pastels, draws in pen and pencil, and does photography.

Asthma prevented the young Tsuchidana from playing outside much, so he traced comics instead, fostering his lifelong love of art. A pivotal moment in his early artistic journey came when he was 12.

"I had a dog named Dime. He and I would go everywhere so I could draw and watercolor," Tsuchidana says. "One day, we went down to the end of Waipahu Depot Road. That road ends at Pearl Harbor. I saw a barge and I started painting. After a while, I looked around for Dime and I saw a tree. And I put that tree into my painting. I realized at that moment that artists can move mountains."

After graduating from Kaimuki High School in 1952, Tsuchidana joined the Marines.

"That changed my life. I learned discipline and pride. The military teaches the lessons of life. And you know, once a Marine, always a Marine," he says.

Tsuchidana's "Form and Light," above, from 1988, is a pastel and charcoal with wash on paper.

"He taught me everything I know in art," Tsuchidana says. "He told me to study Cézanne. If you study him, you're studying all the artists, he said.

"Once, I went to a lecture given by (painter) Karl Knaths. He gave the worst lecture -- he mumbled and he fumbled. But the butler made me promise to go find him. He said he was a 'nice man.' So I found Karl's house and knocked on his door. He asked me what I thought of (American abstract painter) Stuart Davis' work. I told him it reminded me of riding in a taxi at Times Square. With that, we became good friends.

"Just talking to Karl and looking at his work, that was enough.

"On the way to Karl's house, I met (abstract expressionist painter) Hans Hofmann in a barber shop," Tsuchidana continues. "He was cutting his hair.

"I introduced myself. When I was leaving, he asked me what I was going to do for the summer. I didn't have plans, so he found me a job helping a cook in Provincetown.

"From Hans Hofmann I learned to be helpful to others."

Tsuchidana later moved to New York, and he married Violet in 1958. In 1960, the Tsuchidanas returned to Hawaii for six years, then moved to Los Angeles for another six. By then they had a 6-year-old son. They came back to Hawaii for good in 1972. Tsuchidana taught art at Kaimuki Adult Education and the Academy Art Center, and has since retired from teaching.

The piece is part of Tsuchidana's "Stage" series, which the artist began in 1979. Tsuchidana says these paintings "have changed the way I look at things." Examining a block of color in relation to the stripe of color next to it, looking at the contrast and balance of the colors, offers a new way to look at life. "You can look to the left, the right, the side, etc. It's an equation of balance, of equal weight," he says.

"It's like a boxer hitting the punching bag or a singer exercising his voice. It's practice," he says. "I do this everyday so I'm 'on.' Bumpei (the late Hawaii sculptor Bumpei Akaji) used to say I'm overproductive, but that's how you grow."

He grabs a bunch of papers from the top of one stack and flips through them. They're drawings of female anatomy. "I've done thousands of these," he says, laughing. "They charge me up in the morning."

In the studio, Tsuchidana's lighthearted stream-of-consciousness relationship with the world disappears. In its place is a quiet, focused, serious energy that has specific intention. Right now, his intent is on abstract paintings forming "The Stage" series. Some half-dozen works of the day, of wide and narrow vertical stripes of various colors, are drying on the floor propped up along the workroom walls.

Yet for all the focused energy, Tsuchidana says he has a fickle personality. To keep boredom at bay and the creative juices flowing, he accesses numerous "wells" of artistic expression: tempera painting, watercolors, pastels, pencil-and-pen drawing, nudes, abstracts and photography. "When one well is going dry, I tap another one," he says.

At the heart of Tsuchidana's artistic evolution is Violet, a retired teacher who keeps her husband's stream-of-consciousness life in order and his artistic integrity the top priority.

"Vi is called 'count your blessings.' She's my rock. Without her I'd be homeless in New York right now," Tsuchidana says.

"(Local art critic) Joan Rose once wrote that artists don't have to believe in what they create or like what they create, they just have to do it," Tsuchidana continues. "That helped me break down the wall.

"When I have a show, there's no pressure for me to try to sell my works, because Vi says don't worry about it, just have a good show. So I don't have to (pander) -- that would kill me. I have the freedom to go as far as I possibly can."

"Visions, Visage" by Russell Sunabe is among the works on display.

Harry and Violet Tsuchidana married in New York in 1958, when the abstract movement was in full swing in the city. Harry and Vi celebrated with best man Tadashi Sato and friend Satoru Abe, local artists who were also credited with bringing abstract painting to Hawaii.

Click for online

calendars and events.