|

Good times

in the Blue

Hawaiian Airlines: 1925~2004

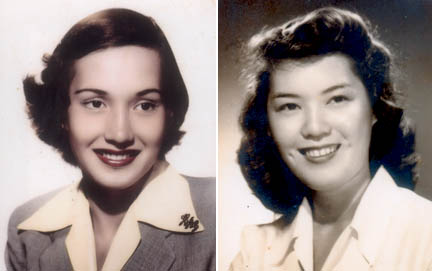

Peaches Riley Smith was fresh out of high school when hired by Inter-Island Airways, Ltd. -- now Hawaiian Airlines -- as one of the company's first "hostesses."

"I was thrilled," said Smith, 76, about her flying days from 1946 to 1948. "It was a coveted and glamorous job. Everybody wanted to be one."

"I was thrilled," said Smith, 76, about her flying days from 1946 to 1948. "It was a coveted and glamorous job. Everybody wanted to be one."

Smith certainly fit the airline's qualifications: The Kaneohe resident was part Hawaiian, measuring between 5 feet 2 inches and 5 feet 6 inches in height, and weighing between 100 and 130 pounds. And attractive.

Smith reveals a secret she's kept hidden for more than half a century.

"I've always been susceptible to motion sickness," she said. "That's bad for an airline hostess."

Perhaps to Smith's credit and stamina, she never got sick before her passengers.

"When I had an early-morning flight, I would eat poi or crackers," she said. "But when someone got sick and I had to rush a carton to them, then I would have to run to the bathroom because I was sick.

"The airline never found out."

Nora Kaaua, 88, of Kahala, flew only for six months but remembers a lot of sick passengers in the early days of flying because they were accustomed to boat, not plane rides.

"You could see it coming," Kaaua said. "They'd swallow their spit, then all hell would break loose. The smell made everyone else sick and we had to clean it up."

|

HAWAIIAN AIRLINES, which celebrates its 75th anniversary on Thursday, was the state's first commercial passenger air carrier. And like its mainland counterparts, there were strict codes of conduct and dress for flight attendants.

Joining Smith and Kaaua were more of the airline's first attendants: Mercy Bacon, 76, Kailua; Carol Mae Vanderford, 75, Alewa Heights; Floraine (Floadie) Van Orden, 76, Waialae-Kahala; and Abigail Funn Chong, of Kailua (no age given).

"The company was so good to us," Chong said. "They would pick us up every morning in a limousine ... because transportation in town was poor."

The women would fly two consecutive days then have two days off.

"We would do three round trips a day, but we'd be at the airport for about 13 hours because you had to wait between flights," Chong said. "We'd start at 6 a.m. and get home at 8 p.m."

The women, except for Kaaua, were hired out of high school, excited about the opportunity for neighbor-island travel and meeting people from all over the world.

"If you were a people person, there was no better work," Smith said. "I loved going to work."

Starting pay was $150 a month with two raises a year and a cost-of-living increase, Chong said.

|

IN 1930, a young nurse and a Boeing Air Transport employee had an idea, proposing that registered nurses would make ideal additions to the flight crew to take care of passengers who got sick. Boeing, then an airline as well as plane manufacturer, hired eight nurses for a three-month trial run. The new attendants, called "stewardesses," became an integral part of the airline industry. For decades, airline stewardesses worked under strict demands, including being unmarried and made to wear form-fitting uniforms, high heels and stockings.

Working for Hawaiian, "we could be married but not pregnant," Chong said.

"It was a time when you couldn't go out in public with your belly showing and you didn't feed your child in public," Bacon said. "So can you see the picture?"

That's why these women, with the exception of Van Orden, flew only three years. Van Orden was at Hawaiian for 11 years, from 1948 to '59.

Smith remembers having to wear 2-inch heels, stockings, a panty girdle and either a summer or winter suit. To maintain the company image, hostesses were prohibited from walking around in public in uniform with their hair in curlers or a ponytail, or while smoking or drinking.

When Chong and another flight attendant got their ears pierced, they wore the earrings backward, hiding them with their long hair.

"We didn't want to get caught by management or we would have been suspended for two days," she said.

|

Another "hostess" who arrived at the airport sans stockings faced immediate suspension.

"In those days, the hose had to have a seam," Van Orden said. "So this girl took a dark pencil and drew a line down the back of her legs."

The women recall being harassed by ramp agents and ground crews, but rarely pilots.

"Pilots were of a high order," Bacon said. "They treated us like a big brother, took care of us."

Unruly passengers were handled by pilots and co-pilots. But passengers' needs were the hostesses' responsibility.

Van Orden remembers one passenger who carried a large fishbowl filled with water, fish, sand and decorations on board. "She put it on the floor next to her seat and it turned over mid-flight," Van Orden said. "All the water washed down under the seats and into the aisle. There were fish flopping around, and the passenger behind her had his shoes filled with sand and water."

Van Orden used paper cups to scoop up fish and water when the pilot yelled back that all the running around was shifting the plane's center of gravity.

"What's going on?" he said.

"We're fishing," Van Orden yelled back.

Another passenger flying from Lanai to Maui walked up the ramp and dropped a large, partially wrapped, bloody aku in Chong's arms.

"It was slimy and streaked with blood," she said. "I put it in a small compartment and said nothing. We were taught to be polite."

The women remain close friends and eight years ago created a flight attendant club, Koa'e Kea, or "high-flying white bird," with 80 members meeting twice a year.

"It was a wonderful phase in our lives," says Smith, who has four children. "Then we moved on."

"It was an innocent time," adds Chong, who has 10 children in a blended family. "We were young and naive and excited."

Kaaua laughs. "Oh yes, we were such cherries."

|

hawaiianair.com

Hawaiian Airlines History

1929

On Nov. 11, Inter-Island Airways, Ltd., launched the first scheduled air service in Hawaii.1941

Name changed to Hawaiian Airlines to pave the way for trans-Pacific operations. Wings logo adopted.1943

First stewardess hired.1952

First pressur-ized, air-conditioned cabin service with 44-passenger Convair 340s; the cost was $520,000 each.1966

Introduced Hawaii's first inter-island jet service with 99-passenger DC-9-10s.

1975

130-passenger DC-9-50s added to fleet. The airlines had the first all-female crew to operate a certified U.S. scheduled flight.1985

Widebody L-1011 aircraft added to fleet. Hawaiian launches service between West Coast and Hawaii.1994

Widebody DC-10s replaced the L-1011 fleet.2002

Boeing 767s replaced all DC-10s.

Pilots and attendants form

tight-knit ohana

MIDWAY through a 45-minute flight to Maui from Honolulu, a Hawaiian Airlines flight attendant was walking up the aisle attending to passengers, when, stopping to retrieve an empty water cup, a male passenger slid his hand up her skirt.

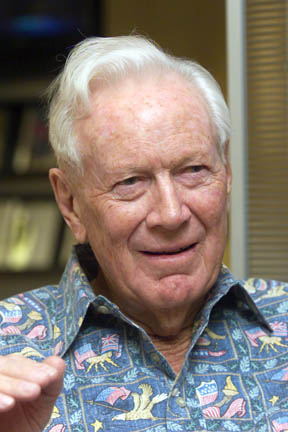

She glared at the man, then rushed for refuge in the cockpit, where Capt. George (Bob) Duncan offered to speak to the man.

"He actually grabbed her," said Duncan, 83, who retired from Hawaiian Airlines in 1981 after 31 years of piloting. "She said she'd take care of it.

"She'd filled up a tray with cups of pineapple juice, then, well, stumbled and it fell over the guy," the Kailua resident said.

When the plane landed, the passenger told Duncan he was filing a complaint to have "that stewardess" fired.

"I said, 'Certainly, sir, you should do that and I'll even provide you with the address of Hawaiian Airlines president Bob Magoon. But you're a married man, aren't you, and of course we'll have to tell your wife all the details.'

"No complaint filed."

It wasn't standard operating procedure for dealing with sexual harassment, but in the airline's early days, those in the air and on the ground thought of themselves -- not as pioneers in the state's aviation history, as they were -- but a tight-knit ohana "that really cared for and protected each other," said Duncan, who began his career with the airline in 1950.

"It sounds melodramatic and self-serving," says Capt. William H. Noyes, who will retire after 37 years in April, "but we like each other."

Another former pilot and later a Hawaiian executive, Robert Maguire, 79, said, "We spent so much time in the air or at the airport that we were always talking and knew about one another's lives." Maguire retired in 1983 after 33 years.

Hawaiian Airlines, which marks its 75th anniversary on Thursday, started as Inter-Island Airways, Ltd., operating out of Honolulu's John Rodgers Airport, now Honolulu International Airport, offering the state's first scheduled interisland flights. Two eight-passenger Sikorsky S-38 amphibian planes began three weekly round trips between Honolulu and Maui and Hilo.

W. Leo Rankin, 84, a 32-year-Hawaiian Air veteran who worked there from 1948 to 1980, remembers his early days of flying DC-3s "down in all the weather" on interisland commutes, with no autopilot.

"We were allowed to fly on an instrument flight plan but used visual flight rules," he said. "Usually when we flew to Maui, we'd fly around the north side of Molokai, dropping down to 2,000 feet to give passengers a good view of the cliffs and coastline.

"We always wanted to give passengers the most comfortable, enjoyable ride possible."

|

DUNCAN, NOYES, Maguire and Rankin have more than 133 years flying experience with Hawaiian. Peeking inside Hawaiian's newest cockpits filled with instruments, dials, screens and levers, the three retirees seemed unimpressed.

"It's an airplane," Duncan said. "It just has a little more of everything we had."

Maguire, who was born in Glendale, Calif., and Duncan, from Honolulu, learned to fly in the military; Rankin and Noyes are civilian-trained. They all love flying for various reasons.

"I decided to be a pilot when I was 3," Noyes said. "We were living on an Illinois farm when my parents took me on a trip on a Super Constellation in the dead of winter.

"After I got on the airplane, I took a nap, and when I woke up, we were in Miami where the sun was out. At that moment, airplanes were magic to me; I always felt connected to them."

So connected that when Noyes talks about an aircraft, it's difficult discerning whether he means a person or a flying machine.

"I love establishing a rapport (with the airplane), feeling connected to it, having a oneness," said the husky 6-foot-4 pilot. "(The plane) really does speak to you, through subtle vibrations and sounds and pressures. You have to familiarize yourself with every aircraft. Only then can you make it do your bidding."

A grinning Rankin nudged Duncan after hearing Noyes' comment.

"Well, what I remember is the acceleration down the runway, that thrust," Rankin said. "Talk about exhilaration. I just like being in the air."

Maguire, a modest man with a soft voice, admitted, "I wasn't born to fly like these guys."

"The war happened and everyone was going in and I was looking for a good job. ... I preferred flying to being a ground soldier," he said. "But I stayed with Hawaiian because I liked the company and the people I worked with made it fun to come to work."

Duncan, who started as a mechanic, decided, "I wanted to fly airplanes, not work on them."

Rankin was more pragmatic. "I also was an airplane mechanic, but when I realized pilots were making all the money and I was doing all the work, then I started flying," he said.

Piloting for an ambitious airline in a growing state was filled with challenges.

Rankin was co-piloting a DC-3 when a flight attendant told him a male passenger would not stop smoking, even though it was prohibited. Rankin talked the man into stopping, only for a flight attendant to discover the man smoking in the bathroom. The craft's top gun, Capt. "Bud," unlatched the bathroom door and ordered the passenger to put out the cigarette and return to his seat.

"The guy asks Bud for a glass of water," Rankin says. "Then he pulls out a cigarette, tears the paper off, and dumps the tobacco in the water and drinks it. 'Any law against that?' he says.

"So Capt. Bud looks him right in the eye and says, 'Want more water?' I learned a lot from Bud."

Duncan said all Hawaiian's co-pilots learned what it took to be captain from the pilots they worked under.

Noyes, Hawaiian's employee of the year in 2003, said Maguire, Rankin, Duncan and others not only helped him to improve his flying skills but his rapport with passengers.

"Bob is the ultimate gentleman," Noyes said. "When I would make a mistake, he would correct me and give information in such a matter than it didn't take away my dignity. He never made me feel beat up."

The Mokuleia resident was hired as a first officer in 1968 and earned his stripes as captain 13 years later.

Co-pilots often shared notes on the captains' personalities.

"You'd do as much research as you could to find out their likes and dislikes," Noyes said. "You did hear about Leo the lion, didn't you?"

Rankin laughed.

"Never had trouble with anybody who really wanted to do the job," Rankin said. "But you'd occasionally have a co-pilot who, as soon as you rounded Diamond Head, would pull out his Playboy when he should be looking out the window."

Noyes said a captain's responsibility is "to create a professional yet comfortable working environment." He speaks to customers in the gate area before boarding, describing the route, even flight conditions.

When Maguire, Duncan and Rankin started rambling about practical jokes and pranks crew would play on one another, they insisted the anecdotes were off the record. Noyes remembered Capt. Joe in particular. After pulling a series of jokes on a flight attendant, the woman vowed to repay him.

"So one night after taking off from Kona, she knocks on the cockpit door and hits him in the face with cream pie," Noyes said. "He was laughing so hard he's choking, and she asks, 'Hey Joe, what flavor is it?' When he doesn't answer, she hits him again with the pie."

It wasn't funny to a passenger, who wrote a letter to Magoon complaining about the lack of professionalism and suggesting the woman be fired.

"Joe went to see the boss and successfully lobbied not to fire her," Noyes said.

NONE OF THESE pilots approve of the Federal Aviation Administration rule that forces pilots to retire from commercial airlines the day before turning 60. That'll be in April for Noyes, who plans to continue piloting on corporate jets.

"I'll still have flying, but I won't have guys like this around anymore, or the crews who are like family," he says.

Noyes carries one memory that, for him, symbolizes Hawaiian's ohana spirit. A 50-year employee was terminally ill with cancer and wanted Hawaiian to take him home to Kona.

"Management granted his wish, even though the only available aircraft was a massive 305-seat TransPac DC-10," he said. "We flew him home with 74 friends, co-workers and family. From the cockpit I could hear Hawaiian songs, ukuleles, a big bass fiddle.

"We flew him over Haleakala crater and past the old Upolu Point airport, where he first worked for Hawaiian while in high school. Then we made a victory pass down Kona runway. When we landed, there were 200 friends to meet him and airport fire trucks spraying an arch of water."

Noyes' voice softened.

"Would I stay with Hawaiian if I could? In a heartbeat."

Click for online

calendars and events.