MAKAI ]

MAKAI ]

|

‘I felt like an

outsider looking in’

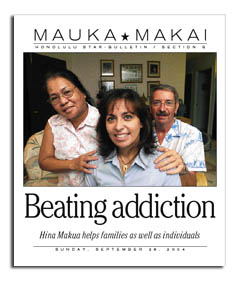

Hina Mauka provides a safe haven

for those struggling with addiction

MARIA Carpenter grew up believing in the accessibility of the traditional American dream, complete with a white picket fence, 2.3 kids and a dog.

Unfortunately, she took an early detour.

She started smoking marijuana when she was 14 and graduated to harder drugs. "It started with a dabbling of curiosity and interest," she said. "It was like cancer. It spread and got to a point where it started becoming an everyday thing."

Hina Mauka assists families, tooFamily members can attend Hina Mauka's Family Education and Counseling program even if an addict in not yet in recovery. Participants focus on communication skills and ways to intervene with the family member or friend.Attendees are provided an opportunity to understand their role in the recovery process, get support and begin to develop a program to ensure their own well-being. Programs are offered at the following locations: » Kaneohe: 7 to 8:30 p.m. Thursdays at 45-845 Pookela St. Call 236-2600. » Waipahu: 10 a.m. to noon Sundays at 94-216 Farrington Highway. Call 671-6900. » Waianae: 7 to 8:30 p.m. Thursdays at Ka Hana O Ke Akua Church, 86-311 Lualualei Homestead Road. Call 671-6900. » Kauai: 6 to 7:30 p.m. Tuesdays at 2970 Haleko Road, No. 103. Call 245-8883. » Maui: 7 to 8:30 p.m. Wednesdays at 270 Hookahi St., No. 301. Call 242-9733.

|

"I have lots of unfulfilled dreams," she said. "Drugs don't lead to anything except a dead-end, one-way street."

But try relaying that message to the next generation of thrill seekers. Many have to learn the hard way. Fortunately, Hina Mauka was established to help those ready to start over. The organization provides a safe and supportive environment for those needing to learn how to deal with addiction and was Carpenter's saving grace.

"I felt a sense of empowerment. I was on the right path," she said of entering the program. She had grown tired of the cycle of addiction and treatment, and expecting an outcome that did not materialize, while refusing to believe she had a problem.

"I was in control and knew everything. I didn't need help finding answers. I was both a control freak and a perfectionist," she said.

Carpenter's parents, George and Alfreda, attended concurrent classes for family members.

"We felt like we were out in the middle of the ocean with no life preservers," said George. The treatment facility at Hina Mauka gave the family techniques to cope, as well as assist.

Too often, well-meaning actions do more harm than good. "We learned about the terms 'rescuing' and 'enabling' as opposed to helping an addict," George said.

"When other people shared their stories, we could relate to various aspects," he said. "It made me feel all giddy inside. We were not alone."

One doctor used an analogy of diabetes, which lifted the family's sense of shame.

"Addiction is a disease. How an individual manages it determines the rest of their life and successes," George said.

COCAINE WAS CARPENTER'S downfall. For more than eight years, she said, "I hung out with yuppies, young urban professionals with good jobs and a good education. They were also weekend coke users.

"We would work hard all week. On the weekends we would go bowling, shoot pool or even play board games. We also had drinks and cocaine."

Recreational use turned to addiction, which worsened whenever she experienced relationship problems. Drugs were used "to hide and mask the pain," she said. "Instead of gambling or exercising, I chose drugs. I don't think I'm all that different from anyone who is trying to deal with the pains of everyday life."

She said she tried to quit drugs cold turkey several times and could stay away for a year or even two, but "if my relationships started to flounder, the cycle would start all over again. If life got too tough, I would run and hide."

|

THERE IS NO typical profile for drug abusers, and on the surface, Carpenter looked every bit the success. She was working as a legal secretary in Houston and attending law school, maintaining a grade-point average of 4.0.

But addiction can affect anyone, she explained. "The disease does not discriminate. Anyone is susceptible. My parents were social drinkers. I don't come from a broken home, and I was not abused."

She never graduated as planned. She lost focus and started bouncing from job to job.

"My priority was getting up in the morning and getting high. I blew all of my money and couldn't pay my rent or bills.

"When an addict hits bottom, they realize they need help," she said. Instead of prostitution, begging or living on the streets, she decided to ask her family for help.

"I'd lost enough to make me realize that if I didn't stop, I was going to lose a lot more."

Although she claimed she was not suicidal, "I was not afraid of dying, I was afraid of living," she said. "I was paranoid and didn't know how I was going to get through the day."

She went to her brother-in-law for help. He was a Houston police officer and went to her home in full uniform. "He understands me better than my sister. And he deals with all sorts of people," said Carpenter.

"He had on the handcuffs, gun -- talk about intimidation," she said. "I was wondering if he would slap the cuffs on me and take me to jail."

Instead, he calmly told her, "We will get you the help you need." There was no judgment, she said.

"She didn't call us," said her mother, Alfreda. "We didn't know what was wrong. I went to get her, paid with my plastic card. For the first time, I felt relieved. I didn't have to worry anymore. I felt like everything was going to be OK. Maria entered the Hina Mauka treatment facility and engaged in a 3 1/2-week program."

During her stay, Carpenter attended meetings and learned about her disease. "They help you get back on your feet, get a job or get back in school," she said.

|

She walked away from the program with more self-knowledge. She claimed that every aspect of her life needed to be changed, including ways of thinking, attitude and friends. She also learned that part of her problem stemmed from lacking a sense of belonging.

"I felt like an outsider looking in," she said. "I was not a social butterfly like my sister. I didn't have many friends and was not invited to parties."

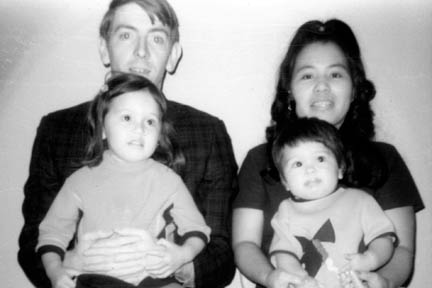

Instead, she was picked on severely by prejudiced classmates as a half Caucasian, half Filipino growing up in Trenton, N.J. "I lived with the pain of how different I was," she said.

"Mom and I come from different cultures," said George. "On the East Coast, they couldn't identify Filipinos with any known group."

Carpenter's school intervened and worked to get her into programs, but once Maria and her younger sister, Donna, graduated from high school, their parents moved to Hawaii without them. It's a decision her parents regret. "We left them fresh out of high school to fend for themselves," George said.

SOBER for nearly two years now, Carpenter, 37, has a different outlook on life. She has started working again, is setting goals and is moving back to Houston this month.

"There is no cure," she said. "I deal with the issues every day. I'm in constant recovery," she said, adding that she is not afraid of seeing her old haunts. "No matter where I live, there is a bar on every corner, and you can find a drug dealer anywhere," she said.

Determination and faith have brought her this far. "As long as I keep doing what I need to do, there is no reason to go back to that neighborhood."

Her suggestion for youths likely to encounter drugs in school: "Don't get caught up in peer pressure. Don't worry about what other people think of you. What matters is how you feel about yourself.

"Kids accepted me doing drugs, but I was really just another person willing to party with them. I've learned that you don't need drugs and alcohol to have fun."

|

Click for online

calendars and events.