Paka‘a’s spirits lifted

by wind for his boat

Paka‘a -- The Sail

Paka'a stood on the beach watching the distant canoes searching for flying fish. The boy knew what exciting sport that was. Twice fishermen had taken him along. He knew how the fish gleamed as they flew over the blue waves, like dancing moonbeams. He knew the excitement of throwing the net over the fish, of diving in to gather up the net and hauling the fish into the canoes. Someday soon the boy meant to go with the fishermen in his uncle's boat.

Yes, the catching was fun, but the long paddle home with a heavy load -- that was hard work. The fleet was close now. As the boy watched he thought there ought to be a way to help the tired paddlers. The canoes were coming before the wind, which helped a little. Why couldn't the wind push with its full strength and bring them home? Then no one would need to paddle.

With a final effort the canoes reached the beach and men began taking out the fish. The head fisherman went to make a thanks offering to Kuula, god of fishing. The other fish were divided: a large share for the chief and a share for every man who had paddled or fished.

"Here's Paka'a!" one man shouted. "Here's the boy who is going to be a fisherman!"

"That is true," said another. "I don't believe there is another boy on Kaua'i who likes fishing as much as Paka'a. Here's a fish for you, boy."

"And here's another." Several men handed fish to Paka'a as they started home with good back loads.

The boy gathered up his fish and went slowly to the house where he lived with his mother and uncle. He cleaned the fish, wrapped them in ki leaves and cooked them over coals. But he was not thinking much about his work for his mind was still busy with the problem of how the wind might push the canoes more strongly.

"Someday soon I mean to go with the fishermen," he thought again. "One boy alone will have a hard time keeping up with the other canoes, for there are as many as eight paddlers in some. I need a way for the wind to help me."

DARKNESS FOUND the boy still busy with these thoughts. The night was warm and he took his mat out on the sand but the wind blew it. The mat seemed ready to fly away. Paka'a rolled on to the blowing edge to hold it down. "This is the way!" he thought and fell asleep.

He was awake at dawn. "This is the way!" That thought was ringing in his head. Sitting up he could see the ocean, huge and dark. But in his mind he saw it gleaming in the sun. He saw the fishermen come in, paddling wearily. And he saw himself in a small canoe steering, not paddling at all, while a mat fastened upright caught the full force of the wind. The canoe was carried by the wind even as a kite is borne along. That was it -- the way he had been searching for! The boy lay down again to plan.

In the morning he went to the hala grove. There was old Hinano gathering hala leaves. She was just the person he wanted to see. She was the best plaiter of lauhala in the village. "Aloha, Hinano!" the boy said! "I came to help you."

"Aloha E Paka'a!" she answered. "Your mother may well be proud of a son who will help an old woman. I need much lauhala today for I must make mats for young people who are building a home of their own. I am glad of help. Take these leaves that are dry but not too old. Don't cut your hands on the edges."

"I shall be careful," the boy replied. He worked fast and the two soon had big piles of leaves. "I'll carry them to your house," Paka'a offered. "I want to see how you make mats."

Old Hinano laughed. "Are you going to be a mat-maker?" she asked.

"I like to see how work is done," he answered. "Perhaps I can help a little."

So Hinano set him to scraping off the prickly edges of the leaves with a sharp shell. "They cut my hands," she told him. He watched her flatten each leaf and roll it over her hand and then strip it. Then he watched her plait the narrow strips of leaf over and under, over and under.

The sun was high when the boy left the old woman and returned to the hala grove. This grove belonged to the district and anyone could use lauhala from it. Paka'a pulled off many leaves and took home a large bundle.

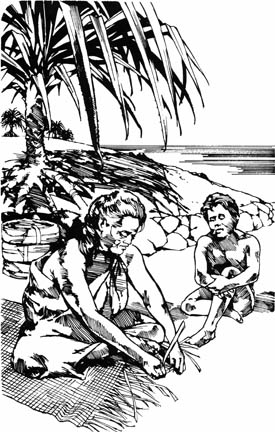

For several days he practiced mat-making. He flattened the leaves and cut them into narrow strips, then plaited. At last he had made a mat that suited him. It was triangular in shape and it was firm and sturdy. He cut and smoothed two poles to hold his mat. He helped a neighbor weed the kalo patch and, as payment, asked for olona cord.

Now if only his plan would work! He must try it. "O Mother," he said, "if I am to be a good fisherman I must learn to manage a canoe. Ask my uncle to let me use his small one. He goes to the lehua forest for birds and does not need the canoe."

His mother objected at first. "You are too young, my son. Wait till you are a strong swimmer." But at last the boy persuaded both mother and uncle.

His uncle helped him carry the small canoe to the water. "What have you there?" he asked when he noticed mat and poles. "If you want to sleep, stay at home. One who sleeps at sea will wake to find himself among the waves."

"I promise not to sleep, my uncle," Paka'a replied. But he had chosen the part of the day when most people would be sleeping. He did not want them to see what he was doing with the canoe -- not yet.

The wind was soft and the sea quiet. Paka'a had paddled before, but never alone. He paddled far out. Managing a canoe alone he felt already a man. Now! The time had come! The boy set up the poles and spread the mat, then turned the canoe toward shore. The gentle, steady wind blew him along. He had nothing to do but steer. His plan was working!

A few days later he joined the fishing fleet. The canoes were going for flying fish. They paddled into the wind. The boy's arms and back ached and he found himself with the slower paddlers in the rear. But he soon forgot the ache of his back and the shame of his slow paddling. Here were the fish! Sparkling, leaping in the sun! Nets were thrown over them and they were dumped into the canoes. It was exciting sport.

At last the canoes started for the distant shore, heavy with fish, even Paka'a's small one. "Want to race?" some men called as they paddled past the boy.

Paka'a let his boat drift for a moment while he put up his poles and mat. "Yes," he called. "I'll race!"

"What is your mat for?" one man joked over his shoulder. "Is the little boy going to have a rest?"

"Yes," Paka'a called back, "the little boy will rest now!" He turned his canoe toward home. A merry wind filled his sail and sent the boat flying through the waves. Paka'a sat in the stern steering, just as he had imagined himself. His small canoe went flying past the big one with eight paddlers. From the corner of his eye the boy saw the men stop and stare at him, then bend to their paddles. But all their work could not send their canoe flying as Paka'a's flew before the wind. The race was his!

Men rushed into the waves to carry canoe and boy up on the sand. A crowd gathered. They examined the mat sail and masts. They told latecomers how the canoe had raced through the waves.

Paka'a made an offering to Kuula, then took home many fish. He carried a few to each family who lived near his home. He carried some to old Hinano and to the maker of olona cord. His uncle cooked the rest and invited friends to feast. "This is a great day!" he said solemnly. "In the years to come every canoe from Kaua'i to Hawai'i will have its sail. Canoes will skim the sea like birds and all men will remember Paka'a."

Next week: The Backbone of a Chief

Click for online

calendars and events.