MAKAI ]

MAKAI ]Remembering the

town that Pele took

Lava crept slowly through Kalapana between April and June 1990, before claiming the sleepy community that fewer than 200 called home. What had been green and inviting became a blackened, alien landscape that was perfect for filming scenes for "Planet of the Apes" in 2001.

At home in New York in 1990, photographer Mary Ann Lynch kept track of the flows through newspaper clippings sent to her, but the news did not surprise or upset her. As her friends in Kalapana said, "Pele cleaned house."

Lynch began documenting the Big Island town in 1971. She was teaching English at the University of Hawaii when her husband Jack applied to participate in the Geography Department Human Ecology Program's Puna Project, sponsored in part by the National Science Foundation, to document isolated Hawaiian communities.

"There was no money, but acceptance meant we were given a place to stay," said Lynch, who had to find her own accommodations anyway because she was very hapai. "I look back now and wonder how I did what I did," she said.

But now she imagines her condition is what endeared her to her subjects at a time when there was rising tension between the kanaka maoli and outsiders as development threatened to overrun a rural way of life.

|

"People took to me, I think, because I was noticeably pregnant, a novelty, and no one felt threatened by me."

The access allowed for intimate photographs and oral histories that captured life in an area that no one could have known would be gone within two decades.

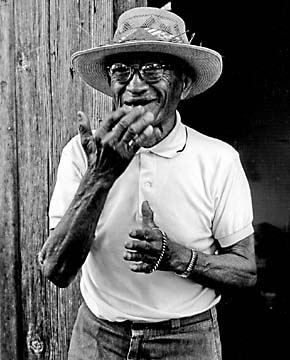

Within that time span, Lynch returned several times to photograph the people and natural beauty of Kalapana. Her photos show people going about their daily tasks: fishing, hunting, making kulolo -- a communal effort -- and playing music. Among the renowned local musicians who grew up in Kalapana were Ledward and Nedward Ka'apana and Dennis Pavao.

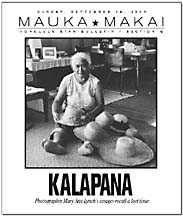

Lynch has returned again, this time as one of the contributors to the 25th anniversary issue of Bamboo Ridge. The anniversary will be celebrated with free readings by contributors to issue No. 84 and a mini exhibition of Lynch's photos, beginning at 7 p.m. tomorrow at the University of Hawaii-Manoa Campus Center Ballroom. Lynch's photograph of master hat weaver Annie Quihano's hands at work forms the cover of the literary journal, and her writing and photos of Kalapana, titled "Kalapana, A Hawaiian Place," fill 16 of its 432 pages.

LYNCH'S INTRODUCTION to the people of Kalapana came with the help of Pahoa High School student interns like Momi Ka'awaloa and Wayne Roberts. "We'd drop in on people because they had no telephones," Lynch said. "I was born and raised in a small place, Greenfield Station in Upstate New York -- we had telephones and all -- but there was something familiar about Kalapana and that backwoods feel that made me feel extremely comfortable from the beginning.

|

"But it was the time of the Kaimu Bay Development Plan, and there was a proposal to build a huge resort at the black-sand beach. My feeling was that it would ruin Kalapana.

"My husband and I arrived in Hawaii in 1968, just nine years after statehood, but the rate of acceleration of change was mind-boggling. We'd joke that were so many pilings in Waikiki that it would tip over and fall into the ocean.

"I knew virtually nothing when I got there, but I knew it was a culture that seemed on the cusp of being overrun by development," Lynch said. "I immediately saw my photos could be used to show life as it is, to say 'Let Kalapana be.' "

When Lynch returned to the lava-covered land, she felt neither sadness nor a sense of loss. She said she simply understood.

"I wished that things could have been left the way they had been, but I also thought that some things get so out of whack that nature or something will step in and restore it."

|

Early flows in 1986 crossed the Chain of Craters Road and claimed 17 homes in the Kalapana Gardens subdivision, stopping development immediately, and lending credence to the Kalapana residents' belief that the volcano goddess will come and take the land if she doesn't like what's going on.

"I'm not Hawaiian. I can't pretend to be Hawaiian. But I know the way Hawaiians are on the land," Lynch said. "No one wants to lose everything, but the Hawaiian way of thinking is very different from the Western way. The Hawaiians understand the cycle. They have total respect for the destructive force of nature, which is also a creative aspect because that's how you get new land. After that happened, the only people willing to build a house there were Hawaiians."

One of the Kalapana residents, Auntie Tootsie Peleiholani, told her at the time, "Kalapana people are like opihi; we cling to the rock."

"Lava is very forgiving," Lynch said. "Ferns came back immediately and the Hawaiians began planting coconuts. They started a tradition -- if you go out there bring a coconut and plant it."

Efforts to rebuild the community continue through the Kalapana Community Association headed by Pi'ilahi Ka'awaloa, who's also spearheading a museum project for the area.

|

A RETROSPECTIVE of Lynch's work brought hundreds to the Lyman Museum last summer, including the children and grandchildren of those she had photographed a quarter-century ago.

"The young ones are the aunties now," Lynch said. "I saw the work impacting three, four generations."

She's hoping to encourage the next generation of documentarians, whether it's through stories capturing island lifestyles and personalities presented in the pages of Bamboo Ridge, or photography. While Lynch is aware of the conceptual photography coming out of the islands, she said, "It's important that we use photography as a vehicle for social change. Kapulani Landgraf's work is a good example. She's really got a social viewpoint, as well as a moral position.

"I think there should be a global awareness of Hawaiian values. 'The life of the land is perpetuated in righteousness,' the state motto, shows that the Hawaiian value system has everything good at its heart and it's a good way to go around in the world: You respect others, you work with others, you revere nature, you live close to nature."

|

In her Bamboo Ridge piece, Lynch wrote, "Kalapana life was hard but social, dependent on mutual support. Many activities related to subsistence -- gardening, hunting, fishing and gathering and preparing food. These often involved more than one person. Being pono (acting right) with one another was necessary."

"This planet will exist," she said. "It's people that are going to kill each other off if we don't start getting along."

To this day, she considers Hawaii to be her second home. While here, she helped to create the Image Foundation, Hawaii Literary Arts Council, the Hawaii Film Board and Greenfield Film Society.

"It's where I came of age as an adult, but also as an individual. I always had my basic values, but that's where they solidified for all time. My friends regard me as a Hawaiian sister or auntie and that's the way the world should be. We are all brothers and sisters under the skin."

|

Click for online

calendars and events.