|

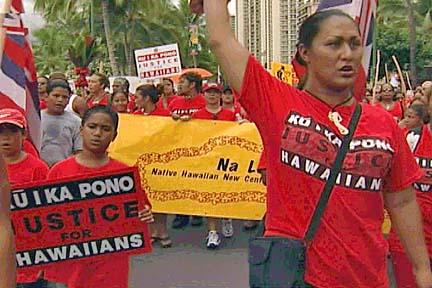

Hawaiian march

floods Waikiki

More than 10,000 take

to the streets in a peaceful

appeal to protect land

and entitlements

Wearing a red "Justice for Hawaiians" T-shirt and struggling to march while carrying a towering pole from which waved a Hawaiian flag, Puuwai Robins of Waianae kept pace with other family members as she marched down Kalakaua Avenue yesterday morning.

"I'm here to stand up for my blood and my culture, and to stand against whatever they do to us that is wrong," said Robins, 10.

Yesterday, Robins and thousands of native Hawaiians, many dressed in red T-shirts emblazoned with the words KU I KA PONO ("justice for Hawaiians"), turned Waikiki's main boulevard into a vast red river to stand up for Hawaiian rights at a time when many feel their rights, lands and entitlements are under attack.

March organizers' and police estimates of participants in the annual parade ranged from 10,000 to 18,000. Afterward, marchers joined a political rally at the Waikiki Shell where activists gave rousing speeches, some groups sought signatures for political petitions and others just enjoyed the Hawaiian food, music and a proud sense of unity despite many differing personal notions of what it is to be Hawaiian.

"This is unity for Hawaiian justice and a gathering of diverse minds," said Lyle Kaloi, a marcher who brought his 3-year-old daughter, Hazel, with him on the parade route.

People held banners or waved protest signs, Hawaiian flags and ti leaves. Some banners said "Stop stealing our lands" and "Protect alii land trusts," referring to the City Council debate over repealing the 1991 law forcing lease-to-fee conversions of property now owned by the alii trusts. Other signs alluded to military issues, such as "Stop Stryker." Some fought for sovereignty, and a few said "Yankee go home" and "The natives are restless."

|

There were groups representing the alii societies and trusts, Hawaiian schools, civic societies, sovereignty activists, Hawaiian cultural organizations, environmental groups and families proud to be Hawaiian.

Bill Souza, wearing the elegant red-and-gold cape of the Royal Order of Kamehameha I, stood with others in their capes, greeting marchers. Speaking of leasehold conversion of alii land, he said, "As a royal society created by Kamehameha I, we have an obligation to protect the land, to keep the trust in perpetuity."

Iokepa Salazar, 28, from Nuuanu, stepped out of the march route long enough to say: "Hawaiian entitlements are at issue, so this is a solidarity march. It's pretty much about justice for Hawaiians."

Some tourists were baffled at the march, and one Japanese tourist persisted in having his picture taken with different members of martial arts groups who carried spears and were dressed in malo that showed off their muscles and cultural tattoos. About 30 or 40 members of martial arts groups kept the parade moving and conducted crowd control.

"This is much mellower than a protest in New York City," said visitor Jovial Kemp, who grew up in New York and lives in Los Angeles. "I had no idea there were people who didn't want to be part of the United States. But if these hotels that make it look like Miami Beach are what Americans brought, then I don't blame them."

The social and political issues drawing out thousands ranged from those concerned about passing the Akaka bill and the repeal of the City Council's leasehold conversion law known as Chapter 38 to those concerned about military expansion and preserving Hawaiian culture, the bones of ancestors and sacred places such as Mauna Kea.

"We're here to support the movement," said Charles Kaaiai, 53, of Kailua, who marched with his wife and two children, ages 9 and 11. "There are many issues. There's leasehold conversion, Stryker, Mauna Kea and the native Hawaiian charter schools. It's been too long since we've been protesting -- since 1893 and the overthrow."

With obvious pride, Kawika Haae, 31, of Kapolei, who was among the early waves of marchers, stood on the balcony of the Aston Waikiki surveying the final waves of the marching red tide passing below him to the end of the route.

"This is about giving power back to the Hawaiian people," said Haae. "I am concerned about Hawaiian homelands. Some people spend their entire lives waiting to be issued a lot."

Haae, who has been waiting 12 years, said, "I would hate to die waiting."

|

Vicky Holt Takamine, a kumu hula and president of the Ilioulaokalani Coalition, which organized the march in conjunction with many other groups, said after the march: "The streets were packed. It went well."

Takamine said: "The whole point is to bring our people together and to share in a common struggle to protect our lands and our rights. We are also encouraging people to register and get out and vote."

At the grounds around the Waikiki Shell, information booths were set up, representing a variety of political issues with volunteers urging people to sign petitions. At the Repeal Chapter 38 group, Nona Akana hoped to "get hundreds and hundreds of signatures."

Another booth hoped to get signatures for a moratorium on military expansion.

And at the Kau Inoa table, longtime activist Charlie Rose encouraged people to fill out registration forms "because if we're forming a native Hawaiian government, we need plenty of people to be part of the process."

Also at the Waikiki Shell, there was music, chant and dance interspersed with political speeches.

Lilikala Kame'eleihiwa, a professor at the University of Hawaii's Center for Hawaiian Studies, spoke in a booming voice over a microphone. She told the crowds: "We're going to march a lot more. It's going to get a lot worse before it gets better."

Referring to the city lease-to-fee conversion, she said, "It's time for the City Council to stop stealing our land."

She urged people to show up at Council hearings, saying, "If we have 6,000 people at City Council, I think they won't steal our land."

She asked the crowd, "Do we want our land?"

The crowd roared back, "Yes!"

She asked, "Do we want our justice?"

"Yes!" the crowd yelled back as many fists punched skyward.

"Then we will have to fight for it."