|

Novel birth control

catches on

Isle women seeking lasting

contraception try the new

Essure nonsurgical implants

A new method of permanent birth control that does not require an incision is being performed on women in Honolulu.

The procedure achieves the same results as a male vasectomy or female tubal ligation in preventing pregnancy permanently. But it is the first alternative that does not involve cutting or penetration of the abdomen, said Dr. Tod Aeby.

A professor of obstetrics-gynecology in the University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine, Aeby runs the OB/GYN residency program at the Kapiolani Medical Center for Women & Children.

He was the first physician to begin using Essure here about six months ago after training in the procedure. He has performed it on about a dozen patients so far and has been teaching or supervising other doctors in its use.

A big advantage, he said, is that it can be done in about 35 minutes in the doctor's office without general anesthesia. Most women return to normal activities within 24 hours, he said.

Tubal ligation procedures, which about 700,000 American women undergo each year, are usually performed in a hospital because they require anesthesia and an abdominal incision, Aeby said.

They involve placing bands or clips around the fallopian tubes, cutting and tying the tubes and applying an electric current to burn the tubes. Recovery can take four to six days.

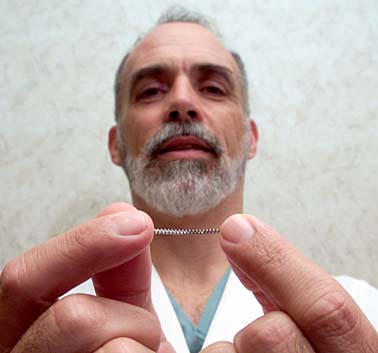

Essure involves a small, flexible device called a micro-insert made of polyester fibers, nickel-titanium and stainless steel materials. It is like a little spring, Aeby said, explaining it is coiled when inserted and pops open when it is in place and released.

The doctor passes a telescopelike instrument called a hysteroscope through the vagina and cervix with a video camera attached to look into the uterus and position the micro-inserts at the opening of the fallopian tubes, where eggs travel from the ovaries to the uterus.

"The wire is small and kind of delicate. We have to be precise," he said.

Once the micro-inserts are in place, tissue grows around them and blocks the fallopian tubes to prevent sperm from reaching and fertilizing an egg.

Since no cutting is involved, Essure does not cause scars. "All other procedures for interrupting the tube require incision, in the belly button usually," Aeby said.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved Essure in November 2002 after two clinical trials showed 99.8 percent effectiveness after two years.

It is believed to work throughout a woman's reproductive life, but no birth control method is 100 percent effective, Aeby pointed out. Also, Essure has not been used long enough to determine its failure rate, he said.

Another type of contraception must be used for about three months until an examination confirms that the tubes are blocked.

The Essure procedure is considered irreversible and should be performed only for women who are "very, very certain" they do not want more children, Aeby said.

All tubal procedures have risks, he said, noting about 30 percent to 50 percent of pregnancies after tubal ligation are ectopic -- occurring outside of the uterus, usually in a fallopian tube.

If a pregnant patient has had tubal surgery, physicians try to make sure the pregnancy is in the right place, he said.

About 12,000 women have had the Essure device inserted so far, and no ectopic pregnancies have been reported, Aeby said. "But it's a new device, so we don't have experience to say what the rate would be. We have to assume it's like any other tubal procedure."

Most of his Essure patients have been in their late 30s or early 40s, he said. "They made families and didn't want to worry about contraception anymore."

About 40 percent of women under age 25 who have their tubes tied regret it later, and doctors are reluctant to do permanent procedures on women that young, Aeby said.

"We try to counsel them as best we can. We tell them, '40 percent of women just as sure as you are right now regret it later on.'"

He said he tries to guide young women toward an intrauterine device as an alternative because it "works very well" for birth control and can easily be removed if they want to become pregnant.

Essure cannot be used for women who were recently pregnant, who are allergic to nickel or metal or if there is concern about infection of the cervix or uterus, Aeby said.

Complications can occur with Essure, as with any surgical procedure, he said.

But nearly all of the 700 women who participated in clinical trials rated long-term comfort and satisfaction with the device "good" to "excellent," according to the studies.

www.essure.com