University of Phoenix

lowers entry age to 18

You still won't find dormitories or a football team at the University of Phoenix. But starting this fall the giant, for-profit university system will have something to make it look more like a traditional college: 18- to 21-year olds.

Throughout its 28-year history, the company has catered to working, older adults, eschewing ivy-draped campuses for classes in office parks or over the Internet.

|

But looking with its rivals for a way to match the explosive enrollment growth of recent years -- and unable to ignore predictions that California alone will be short 700,000 higher education slots within a decade -- the University of Phoenix is dipping down.

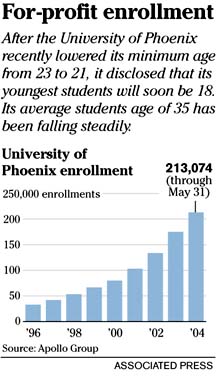

After recently lowering its minimum age from 23 to 21, it disclosed on an investor conference call that its youngest students will soon be 18.

"We have turned away tens of thousands of potential students to this point," Todd Nelson, president and chief executive officer of Phoenix-based Apollo, the university's parent company, said on a conference call last month, during which he also noted the California predictions and the opportunity they present.

The University of Phoenix, which enrolls 213,000 students and has campuses in 30 states, is downplaying the change. It says it has no plans to try to become a full-time college for traditional students, and it won't start recruiting in high schools.

But the announcement, though not entirely unexpected, has prompted questions from analysts who follow the industry.

They wonder about the potential impact on the learning experience in University of Phoenix classrooms and chatrooms.

What if older students choose Phoenix because they like the idea of learning with people their age who have useful life experiences to share?

Will middle-aged students want to collaborate on a research project with a teenager?

And, is the market for nontraditional students maturing?

The company hopes to enroll younger students this fall, but Apollo spokeswoman Terri Bishop said details haven't been finalized.

She said that, in practice, younger students will almost certainly be segregated, since older students generally already have some credits and take different courses.

Still, "in theory, as these students age, then they might mix them," said Jeff Silber, an analyst who follows the company at Harris Nesbitt. "That's definitely a concern."

The move comes against the backdrop of an abrupt reversal to several years of explosive stock price increases across the for-profit education sector.

One culprit has been a string of shareholder lawsuits and federal investigations into bookkeeping practices which -- while not directly affecting Apollo -- have hammered stock prices throughout the industry.

Another problem is what analysts call "the law of high numbers." As enrollment rises, it becomes harder and harder to achieve the same percentage increase every year -- and growth is what investors care about.

Last week, the whole sector fell sharply following disappointing enrollment numbers from just one company, Career Education Corp.

Stocks fell again yesterday when Corinthian College Inc. lowered earnings projections. Corinthian's stock closed down 45 percent, while Apollo's fell $6.30, or 7.5 percent, to close at $77.25 on the Nasdaq Stock Market.

The University of Phoenix was unusual in the industry for having age minimums at all.

Though its average student age of around 35 has been falling steadily in recent years, that's still higher than rivals.

A typical Phoenix student is already in the working world and looking to bolster skills and credentials with an undergraduate or graduate degree.

The company relies mostly on part-time faculty, and about half of its students are in online programs.

At Devry, which accepts students as young as 17, the average age is under 28, and one-third of its 41,000 undergraduate students are under 21.

ITT Educational Services, with 38,000 students nationwide, accepts students as young as 16 in some states. The company won't release its average student age, but says both the number and percentage of students who come straight from high school are growing.

But because Phoenix has always branded itself for older students, its announcement prompted questions about whether Apollo is making this move from a position of strength or weakness.

The company says strength, pointing to its 28 percent enrollment growth in the last quarter, which pushed up revenue nearly 36 percent to $465 million and profits up 47 percent to $109.3 million.

Still, online enrollment growth has slowed, and while Apollo's shares -- trading around $85 -- have fared better than rivals, they're still down from their June peak of $98.01.

Does expanding the student pool "indicate you've kind of gone as far as you can with your previous pool?" said Alexander Paris of Barrington Research.

"That's what the cynic would say. Or is it an issue of, 'We're helpful to 23 and above. Why can't we be helpful to 18 and above?'"

— ADVERTISEMENTS —

— ADVERTISEMENTS —