The Dobelle Debacle

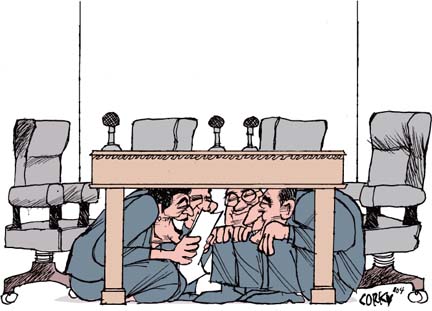

The secrecy surrounding Evan Dobelle's

interrupted tenure as UH president has done

great harm to Hawaii's public university

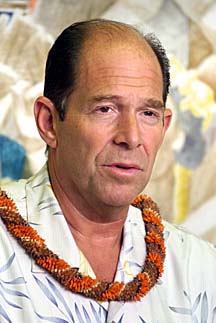

The hiring and surprise firing of University of Hawaii President Evan Dobelle expose the high price and great perils of secret government decision-making in Hawaii.

In a textbook example of a counter-productive public policy, the Dobelle debacle demonstrates that unwarranted secrecy in Hawaii's government does not pay. A key lesson learned is that secrecy breeds a lose-lose policy for citizens -- who are often called upon to foot the bill -- as well as government officials on all sides of a divisive issue and even Gov. Linda Lingle, who has pledged to restore public trust in government.

With the public locked out of knowing why official decisions are being made, secrecy fosters rumors and leaks of information.

University of Hawaii officials have said that depending on the terms of a settlement with fired UH President Evan Dobelle, the cause of his ouster may not be made public.

Unwarranted secrecy works to the advantage of insiders and to the disadvantage of the most disadvantaged segments of society. And, in the Dobelle case, the Board of Regents' decision-making, cloaked in secrecy, has tarnished incalculably the image nationally and globally of Hawaii's only public institution of higher education.

The spiral of secrecy that augured the Dobelle debacle began in early 2001 when the UH Board of Regents met in a series of unannounced, closed-door meetings and agreed to a lucrative contract with Dobelle.

On March 9, 2001, Lily Yao, then-chairwoman of the Board of Regents, signed Dobelle to a contract paying him at least $3 million over seven years and giving him residency in the state-owned mansion near the Manoa campus, use of a state car and a number of other perks.

His first-year salary of $442,000 was more than double that of outgoing President Kenneth Mortimer and four times that of the governor. This multimillion-dollar commitment was agreed to just as the board was raising student tuition and Gov. Ben Cayetano was arguing that the state was too impoverished to increase faculty pay enough to forestall a strike that eventually did occur.

Contesting the secret negotiations that led to such an expenditure of taxpayer monies were graduate student Mamo Kim and the Hawaii chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists (SPJ), who filed a lawsuit in Hawaii's First Circuit Court. They argued that this secrecy violated Hawaii's "Sunshine Law" requiring open meetings of public agencies, except in specific cases permitting closure. This "Sunshine Law" was passed by the Legislature in 1975 in the wake of the Watergate scandal so that opening up closed doors of government would allow in sunshine that acts as a disinfectant to reduce mismanagement and even illegal or unethical decisions.

Unfortunately, graduate student Kim and SPJ lost the case. Circuit Court Judge Virginia Crandall OK'd the board's practice of recessing one closed-door meeting in order to hold another unannounced closed-door meeting without the public and the news media even being aware that the board was meeting or what it was meeting about.

Also unfortunate, the board's secret decision-making on Dobelle's high-priced and lengthy contract sent the wrong signal to the incoming president that money was no object at UH. Dobelle assumed the presidency on July 1, 2001, just 72 days before the spectacular attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon sent Hawaii's struggling tourist-based economy into an even steeper nose dive.

The rest is history -- and a lot of news stories. Dobelle brought in his own management team from the East Coast, paying members up to twice the salaries of the veterans they replaced. He recommended -- and the board agreed -- to pay double his own salary to UH's head football coach June Jones. And Dobelle racked up a tremendous cost overrun in refurbishing his state-owned residence.

Dobelle's public aura of extravagance was magnified by his driving around campus in his pricey Porsche, rather than the state car, and buying a million-dollar-plus home while he was living rent-free in the president's mansion, College Hill. The governor is the only other state official granted the privilege of a state residence -- and hers is now considerably less impressive than the university president's.

The spiral of secrecy continued. In March of this year, the board was reprimanded by another state agency -- the Office of Information Practices -- for the way it conducted secret meetings to evaluate Dobelle's performance.

Then, on June 15, while Dobelle was on the mainland, the board announced that he was fired -- and fired "for cause." Those two little words were a significant way to avoid paying around $2 million to Dobelle for the last four years of his contract, plus fringe benefits. But in trying to stave off a lawsuit by Dobelle, the board refused at the time to disclose to the public its reasons for firing him. The surprise decision -- and the board's secrecy about the "for cause" rationale -- sparked news worldwide.

Now, still refusing to explain its "for cause" decision, the board and Dobelle are holding secret mediation sessions. The board has hired at least three private high-priced attorneys to supplement UH's permanent legal staff to represent it. A mediator, former Attorney General Warren Price, also has been hired.

Mediation is described as a less expensive alternative to a lawsuit. But even if it succeeds, it is costing Hawaii's taxpayers plenty. And secret mediation sessions continue to keep the public in the dark while open court sessions would have been excruciatingly revealing.

The folly of unwarranted secrecy in Hawaii's government operations already has been recognized by some city and county officials. The Honolulu City Council has called for mandatory "Sunshine training" that details open-meeting requirements and philosophy for members of city boards. Mayor Harry Kim provided all his top administrators with open-government orientation when he became chief executive of the Big Island.

The state Office of Information Practices will be conducting training sessions in August for other boards and commissions, but that office needs more resources. It has a fraction of the number of attorneys that the University of Hawaii is funding for its own staff and for mounting legal fees for its mediators.

The Dobelle debacle may provide for decades to come a case study in why more needs to be invested in resources that promote inclusiveness and openness, which are essential for restoring public trust in government.

Beverly Ann Deepe Keever is a University of Hawaii journalism professor. The opinions expressed here are her own.

— ADVERTISEMENTS —

— ADVERTISEMENTS —