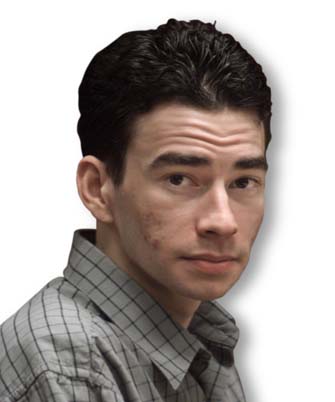

The Aki process

Jurors reveal how they reached

a "compromise" manslaughter ruling

In a small, windowless room, 12 strangers decided in May that Christopher Aki committed reckless manslaughter in the bludgeoning death of his girlfriend's 11-year-old half-sister.

The jury of seven men and five women had listened to a month of witness statements, taken turns holding a bloodied rock and stared at the police photos of Kahealani Indreginal's battered body.

Several jurors told the Star-Bulletin last week that during deliberations, they played and replayed the police videotape of the first of three confessions Aki made. They examined hair samples and debated holes in the police investigation.

And they argued to find common ground, particularly with the few who believed in Aki's innocence.

Just before lunch on the fifth day, the jury voted unanimously that Aki, 22, was guilty of manslaughter, a lesser charge than second-degree murder. Their decision brought a storm of questions, criticisms and editorial page commentaries asking: Why did they go with reckless manslaughter, a charge the prosecutor had told them was typically applied to fatal drunken-driving accidents? Under Hawaii law, murder is "knowingly or intentionally" killing another.

Four jurors separately talked to the Star-Bulletin about their deliberations on the condition that their names would not be used so they could avoid further media or family attention. Four others declined comment, and the remaining jurors could not be reached.

The jurors had taken a pledge among themselves before they left the courthouse May 12 never to speak about their deliberations. But on July 2, Circuit Judge Virginia Crandall sentenced Aki to 20 years, motivating some to talk.

To the relief of several jurors, Crandall rejected Aki's request that he be sentenced to eight years as a youthful offender.

"I feel that with the sentencing, a huge weight has been lifted from my shoulders," one female juror said.

"I couldn't sleep during the trial," said the woman, who will be identified as "Juror A" for this article. "We, as a jury, had a man's life in our hands. But he had the life of that little girl's in his. And we didn't see the pretty pictures of Kahea that were in the newspaper. We saw the other ones."

As jurors, they sat next to one another for a month, always sitting in assigned chairs, taking breaks in the hallway when the judge asked and eating state-paid lunches in the secluded jury lounge.

During the trial, they could not talk to each other about what they heard, let alone say anything to family or friends. They could not look at news accounts. Without work and control over their lives, one juror said they "lived in limbo."

At the end of the trial, the jury was read 47 pages of instructions about how to weigh the evidence.

Once seated in the deliberation room, they were allowed to talk to one another about the case for the first time. They were together every minute unless someone left for the bathroom, and then all deliberations stopped.

A routine, preliminary vote taken the first day shocked some with how split they were: About one-third were adamant about Aki's guilt, another third was just as sure of his innocence because of "reasonable doubt," and the rest were undecided.

"You think that 12 people sit there and hear and see the same thing and come to the same conclusion. They don't," said Juror B.

"I was really frustrated with the whole process," she said. "For me, it was clear and easy: He's guilty, let's vote and go home. But that's not the system.

"There are rules you have to follow. Everyone has to be given their say and the vote has to be unanimous, and some hold out (against a guilty verdict), and then what can you do?"

She added, "It's frustrating to have so many points of view, and not everyone seemed equipped to do this job."

Juror B said: "The system doesn't work. He was guilty, but we couldn't get a unanimous guilty verdict. The result was a compromise."

But other jurors said they argued there was reasonable doubt because the police investigation had holes and Aki told too many different stories.

"There were too many loose ends," said Juror C. "Maybe he did kill her, but the evidence didn't prove it. And after Aki told too many different stories, I couldn't believe anything."

City Prosecutor Peter Carlisle wanted the jurors to believe that Aki had driven the girl away from her family and their Halawa housing complex to Keaiwa Heiau State Park. In a crystal methamphetamine-induced rage, Aki beat her and discarded her body in the bushes, Carlisle said. In a videotaped police confession, Aki said he beat her with a pipe that police never found.

Deputy Public Defender Todd Eddins wanted the jurors paralyzed by reasonable doubt. The defense offered other theories, including one about an uncle who allegedly molested her. The defense said that Aki drove Indreginal to the park to confront the uncle. Once there, Eddins alleged that the uncle became enraged, disappeared down a trail with the girl, stabbed her and dropped a large rock on her several times.

The rock, with Indreginal's blood and tissue on it, was found by an investigator from the Public Defender's Office days after her body was removed.

The defense said the initial police confession was false because Aki was afraid of telling the truth. The defense said the uncle held a gun to Aki's head and threatened to kill him and his family if he told.

Juror C didn't believe Aki's confession or the story about the uncle. He, like others, dismissed the story about the rock, saying it was so big it would have crushed her.

But Juror C was critical of the police investigation, saying "it fell short. HPD just stopped looking. I was surprised. They didn't follow up on things."

He also said it hurt the prosecution's case that "the murder weapon, the pipe, was never found. There was no smoking gun."

Juror C said: "Aki took her there (to the park), and whatever happened after, we don't know. But, he also didn't call for help. He left her there to die.

"The killer is still out there. None of us will ever know what happened up there. But Chris knows."

Juror D also criticized the investigation.

"We had to go with the evidence the prosecution came up with, and it wasn't a slam dunk," he said. "The police fell down. They didn't do their job. They relied on the confession."

He added that if the prosecution hadn't offered the option of manslaughter, "The decision would have been harder. It would have been murder or nothing."

Jurors A and B disagreed, saying the police did the best they could.

"The police work wasn't shoddy," said Juror B. "There wasn't much to be found. The body was decomposed. The weapon wasn't found. I think the police did what they could with what they found."

Aki "was just lucky that nobody saw him and they never found the weapon," she said.

She said she believed Aki's first confession to the police.

"I cried watching it and felt sorry for him. I don't think he meant to do it. I think he was on drugs and everything just got out of hand.

"I think he acted alone and the confession is the story (of what happened). The story on the witness stand was a story made up after the fact to get him off the hook."

Juror A agreed, saying "the evidence supported the first confession." She added that in the taped confession Aki "just seemed so sincere. I don't think he planned it. He couldn't quite believe that he'd done it and he surprised himself."

Juror B said the process of reaching a verdict is like putting together a jigsaw puzzle.

"How many pieces do you need to see that the puzzle is a horse? People have different thresholds. Some people need a few pieces, some need lots," she said.

Star-Bulletin reporter Debra Barayuga contributed to this report.

— ADVERTISEMENTS —

— ADVERTISEMENTS —