The Ala Wai Canal and Waikiki are shown last week in this photo taken from the Ala Wai Manor condominium.

Ala Wai

flood control

studiedA meeting with state officials

and engineers seeks public input

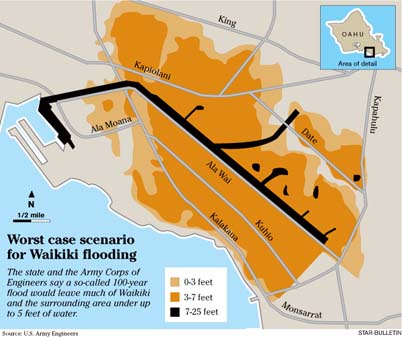

Picture most of Waikiki and much of Moiliili, McCully and Kapahulu 3 to 5 feet underwater.

That's water on the street and running into the ground floor of hundreds of hotels, apartments, condominiums and businesses.

The Ala Wai Golf Course and ballfields, Kaimuki High School, Iolani School and Ala Wai Elementary would be among the places affected if a so-called 100-year storm dumped rain in the Makiki, Palolo and Manoa valleys, according to a U.S. Army Corps of Engineers study.

And it could stay that way for hours, perhaps days, depending on conditions, said Derek Chow, project manager for the Ala Wai Flood Study.

"We anticipate that flooding could be very serious. It would incur severe damage to structures and property and loss in business," Chow said. "I don't think people comprehend the severity of what might happen because it hasn't happened in recent memory."

That's why anyone who lives, works or owns property in the area is encouraged to attend a meeting Tuesday night at the Hawaii Convention Center.

At the meeting, Corps and state Department of Land and Natural Resources officials will explain options for an Ala Wai Watershed flood-control and ecosystem restoration project that could cost $30 million to $60 million and take more than a decade to complete.Measures being considered include:

>> Dredging the Ala Wai Canal deeper and widening the portion makai of the McCully Street bridge.Dredging alone won't prevent significant flooding, Chow said. Neither will walls -- even 18-foot ones as the maximum suggested by early engineering studies.

>> Removing flow obstructions, such as some bridge supports that could be redesigned.

>> Building floodwalls or berms along the Ala Wai Canal and lower reaches of Manoa-Palolo Canal and Makiki Stream.

>> Redirecting some Manoa-Palolo Canal water to a sedimentation basin on the Ala Wai Golf Course, which would also provide flood storage.

>> Building sedimentation/ flood control ponds in the upper reaches of the watershed streams.

>> Removing concrete channels in some stream sections and restoring rock bottoms and natural stream banks.But a combination of dredging and widening the canal, adding some walls or berms, and routing some of the Manoa-Palolo Canal water to storage pools on the Ala Wai Golf Course could work.

Exactly what the solution will look like will be a combination of engineering know-how and what people want.

"We've got a great study team and they've been as thorough as they possibly can," Chow said. "But we are just a few people. We hope people will inform us of things we might not have considered. ... This should be a community plan."

Tuesday's meeting is what's formally called a "scoping" meeting in the federally mandated process for a project that requires an environmental impact study. Community suggestions will be included in a draft EIS expected in late 2005. There will be additional public hearings and opportunities to comment when specifics of the plan are released.

One interesting thing about the flood map is that the area least likely to flood in Waikiki is nearer the mouth of the Ala Wai Canal. That's because when the canal comes out of its bank on the Diamond Head end, it will run through Waikiki to the ocean. The overflow will relieve the pressure on the canal itself, reducing runoff on the marina end.

The Ala Wai area is one of the most densely developed areas in the state, and the canal doesn't have sufficient capacity to carry a 100-year flood event, Chow explained.

"And on the restoration side, really believe we can do some great things that will help to improve the aquatic health in the watershed, combined with community initiatives and other agency actions," Chow said.

The canal can hold a flow of 6,000 to 7,000 cubic feet per second, about the equivalent of a 10-year storm.

By comparison, a 100-year storm would bring a flow of 21,000 to 22,000 cubic feet per second.

Though such a flood hasn't happened since the Ala Wai Canal was built in 1925, it's only a matter of time, Chow says. The buildings and roads added over the years only increase the magnitude of flooding.

The term "100-year storm" refers to the fact that, on average, an event of such intensity happens once every 100 years.

However Pao-Shin Chu, the Hawaii state climatologist, noted that 100-year floods can actually happen less often or more often in any given 100-year period.

"On the Big Island in the last 20 years, we already have had three 100-year events," Chu said.

A November 1965 storm that overflowed the Ala Wai Canal banks and flooded Ala Wai Boulevard was classified as a 25-year storm, Chow said.

Though the price tag for new flood control sounds high, the benefits are worth it, he said.

Just the cost of structural damage from a 100-year flood in the Ala Wai watershed was estimated at $130 million in 2001. That doesn't count property damage, lost revenues from business closures or cleanup costs, Chow noted.

"It's a disaster waiting to happen," said Rick Egged, president of the Waikiki Improvement Association. "There's no question that a flood in Waikiki would be tens of millions of dollars of damages -- damages to businesses, building damage and lost revenue. You shut down Waikiki for a day and the lost revenue is huge."

The study phase of the flood-control work is costing $1.5 million, with 65 percent paid by the Corps of Engineers and 35 percent by the state Department of Land and Natural Resources. The same split would hold for project costs, if approved by Congress, Chow said.

Waikiki businesses are for flood control, but sensitive to how it might look.

Hotels operators want to "make sure appropriate flood-mitigation activities are undertaken as result of this study, but certainly want that to be done in context of a major resort area," said Murray Towill, Hawaii Hotel & Lodging Association president. "We don't want it to have adverse effect on residents or visitors."

Egged said he was happy that the Army Corps and DLNR are looking at the project. "However, it's an extremely sensitive project when you're looking at flood control in the middle of the city," he said. "The community needs to ensure that mitigation efforts put in place are assets to the community," not ugly concrete spillways or high walls, Egged says.

Karen Ah Mai, Ala Wai Watershed Association executive director, said the Army Corps project "has taken us out of the realm of stream cleanups and small restorations to the realm of larger-scale ecosystem restoration."

Association members have always known that restoring concrete channels to natural stream beds would provide better habitat for native animals like the oopu (gobi fish) and opae (shrimp). But doing so was beyond the nonprofit group's reach.

"Now the panorama has been opened and we can now look at these things with hope for the future," she said.

BACK TO TOP |

Meeting details

Some details about the Ala Wai Flood Control Environmental Impact Statement scoping meeting:>> 6:30 p.m. Tuesday , at the Hawaii Convention Center, 1801 Kalakaua Ave., Room 320. Parking will be validated.

>> Written comments may be mailed to Derek Chow, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Civil and Public Works Branch, Building 230, Ft. Shafter, HI 96858.

For more information online about the project, see alawaiwatershed.org

Ala Wai Facts

>> The Ala Wai Canal was built in 1925 to drain the formerly swampy Waikiki.>> A $7.4 million maintenance dredging in 2002-03 removed 186,000 cubic yards of sediment from the canal. Work being considered by the Corps would deepen and widen the canal.

>> The Ala Wai Watershed (Manoa, Makiki and Palolo valleys) is 16 square miles and is home to more than 161,000 people.

>> The Ala Wai 100-year flood plain contains 1,746 buildings.

>> A 25-year storm in November 1965 caused the Ala Wai Canal to overflow its banks, flooding Ala Wai and Kapiolani boulevards and Kapahulu Avenue. The Waikiki rain gauge recorded 2.47 inches on Nov. 11; 1.15 inches on Nov. 12; 2.04 inches on Nov. 13; 0.9 inch on Nov. 14; and 4.13 inches on Nov. 15.

Sources: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, state climatologist, Star-Bulletin files