Hawaii’s

Back yard

Cheryl Chee Tsutsumi

Museum preserves

tsunami storiesFusayo Ito wasn't afraid. She had survived previous tsunamis on the Big Island in 1946, 1952 and 1957, and she was sure no waves, however monstrous, would reach her home in Waiakea, which borders Hilo Bay.

So when the sirens sounded at 8:30 p.m. on May 22, 1960, warning residents that a tsunami would soon hit Hilo, she decided to stay put. Ito's daughter called and begged her to come to her home in Kaiwiki, three miles upland, but the 51-year-old widow told her not to worry; she would be safe.

At 1:04 a.m. a tremendous explosion rocked Hilo, and all the lights in town went out.

Pacific Tsunami Museum

Address: 130 Kamehameha Ave., HiloHours: 9 a.m. to 4 p.m., Mondays to Saturdays

Admission: $7 for adults ($6 for kamaaina), $6 for seniors 60 and older, $2 for children 6 through 17. Free for kids 5 and younger.

Call: 808-935-0926

E-mail: tsunami@tsunami.org

Web site: www.tsunami.org

Ito was overcome by a mighty rush of water, which tossed her about her house like a rag doll. She felt herself falling, then everything went black.

When she regained consciousness, she thought she was still in her house. But, clinging to her screen door, she soon realized she was in the deep waters of Hilo Bay. Knowing that she couldn't swim, Ito was certain she was going to die.

For the next 5 1/2 hours, waves washed Ito in and out of the bay. Miraculously, when dawn came she was rescued by the Coast Guard, but all her possessions were lost, including a satchel containing her life's savings in bonds.

Six months later a bulldozer operator was clearing debris from the disaster when something on the ground caught his eye.

It turned out to be Ito's satchel, dirty and waterlogged but with all of her bonds intact.

Now 95, Ito arrives at the Pacific Tsunami Museum in Hilo every Wednesday morning to share her remarkable story with visitors.

A TSUNAMI IS a series of waves formed by volcanic activity, landslides or earthquakes either under or near the sea. From the source, these waves travel across the ocean at speeds of up to 500 mph. A tsunami's successive wave crests might be hundreds of miles apart, and when they meet shallow waters surrounding a shoreline, they can rise up to 55 feet high. Tsunami translates from Japanese as "harbor wave."

Opened in June 1998, the Pacific Tsunami Museum has a threefold mission: to educate the public about tsunamis; to preserve the social and cultural history of Hawaii; and to serve as a memorial to those who lost their lives in past tsunamis.

The 4,173-square-foot facility features exhibits on the history of tsunamis in the Pacific Basin, the scientific aspects of tsunamis, myths and legends about tsunamis, and public safety measures that go into effect when tsunamis occur. It also safeguards tsunami-related photographs, oral histories, scientific papers, documents and artifacts.

There's also a Keiki Corner where children can read about tsunamis and watch videos designed just for them; the Vault Theatre, which screens videos chronicling survivor stories; and a model of Hilo of a half-century ago, complete with a train running beside Hilo Bay. In this display, video clips introduce viewers to scenes of Hilo, circa 1946, and witnesses to the mighty tsunami that devastated the town on April 1 that year.

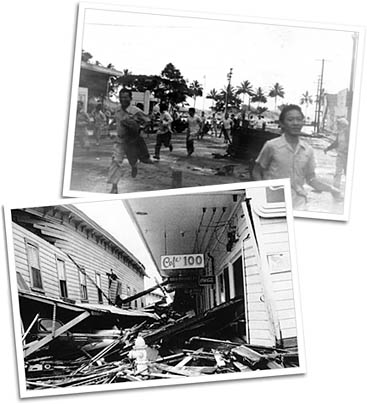

Photographs at the Pacific Tsunami Museum are a reminder of the devastation nature can bring. During the 1946 tsunami in Hilo, George Wong (foreground) was working at his uncle's store, Kwong See Wo, and ran for safety as a wall of water advanced up the street. Albert Yasuhara, left, had been driving his Coca-Cola and missed the first two waves, and ran with the others as the third wave advanced. During the commotion, barber Cecilio Licos, grabbed his new Brownie camera to snap their photo.

The Laupahoehoe Exhibit also recalls that town's tragedy, in which 24 children and teachers were swept out to sea on the Big Island's northeastern coast. A related Amazing Rescues Exhibit recounts three dramatic rescues, one of which revolves around 15-year-old Kazu Murakami.

April 1, 1946, was a special day for Murakami because he was wearing a brand-new pair of shoes and his very first watch in celebration of his older brother's return from a mainland internment camp. When he got to school, Murakami ran to the top of the hill closest to the ocean to get a better view of the incoming tsunami.

A high, powerful wave dragged him into the Pacific, where he kept himself afloat with a chunk of debris. Later that day, an airplane dropped the boy a rubber raft, and he spent a harrowing night at sea, wondering how he would get back to shore.

The next morning, Kazu was excited to see a Navy ship, but his heart sank when it passed him. But, luckily, someone had spotted him, and the vessel turned around to retrieve him. A young sailor named David Cook saw the exhausted lad had passed out, and pulled him to safety.

Three years ago, pictures of Murakami's rescue were donated to the Pacific Tsunami Museum by a man in Texas who had been aboard the Navy ship. Three months after this gift was received, a couple from Los Angeles walked into the museum. They saw the photos and identified themselves as Kazu Murakami's son and daughter-in-law.

Coincidentally, just eight days later, David Cook visited the museum. "I had to come here," he said, "because in 1946 I was aboard a Navy ship that rescued a young boy."

When the museum's director, Donna Saiki, showed him the pictures of that rescue, Cook exclaimed, "That's me! That's the boy!"

Last August, 57 years after the event, museum officials arranged a surprise reunion for Cook and Murakami.

Exhibits show how a history of tsunamis helped to reshape Hilo Town to have an open waterfront and large public parks.

SUCH MOMENTS inspire Saiki, a retired principal of Hilo High School, to maintain an active role at the museum. As the museum's most dedicated volunteer, she puts in a 40-hour week supervising operations, handling administrative duties and serving as the guide for school and tour groups.

"Hilo is a natural location for the museum," says Saiki. "To realize that tsunamis have indeed shaped Hilo, you have to compare the open park space we now enjoy with pictures of old Hilo when all the business and industrial resources were on the waterfront."

She points to records and newspaper accounts dating to the early 1900s that speak about the need to clear the town's waterfront of dilapidated housing enclaves and commercial buildings.

It's understandable why the majority of Hilo's businesses were concentrated there; the railroad ran by the bay, making it easy for merchants to easily unload wares brought to Hilo by train. "Mother Nature, in the form of the 1946 and 1960 tsunamis, accomplished what would have been a hard sell for an urban renewal plan," says Saiki. "Our county leaders also should be credited for their foresight after the 1960 tsunami, when they planned for the relocation of every business and resident from the affected Hilo and Waiakea areas.

"State land was opened for new housing and industrial areas, which enabled us to have beautiful Liliuokalani Park and Wailoa State Park for athletic activities and family outings."

These tranquil scenes belie the fact that a tsunami could strike again at any time. According to Saiki, there were 13 tsunamis in the state in the last century, and in the infant stages of this century, there have been three nondestructive tsunamis. Two of them occurred last September and November.

"There is currently a false sense of complacency in Hawaii," Saiki says. "People don't regard tsunamis as real threats because the last fatal one occurred more than 40 years ago. Three generations of local residents have never experienced a tsunami, and there are many newcomers in the islands who don't even know what a tsunami is."

To this day, tsunami warnings bring hordes to the beach to watch or to ride the waves.

That is why education is a priority of the Pacific Tsunami Museum. "At the museum we are able to impart not only information about the science of tsunamis, but the human-interest stories that go with it," says Saiki. "Our mission is to share as much information with as many people as we can so that no one will ever again die as a result of a tsunami."

See the Columnists section for some past articles.

Cheryl Chee Tsutsumi is a Honolulu-based free-lance writer and Society of American Travel Writers award winner.