Tsunami detectors

work as advertisedScientists acclaim the ocean-floor

sensors for helping to avoid

needless evacuation

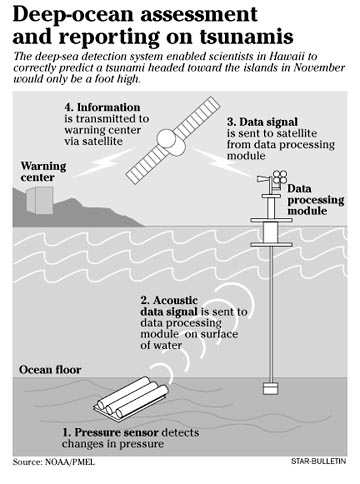

A deep-sea detection system enabled scientists to determine that a tsunami headed toward Hawaii in November was not dangerous and averted a warning that could have disrupted thousands.

A 7.5-magnitude earthquake off the Aleutian Islands at 8:43 p.m. Hawaii time Nov. 16 generated a tsunami that could have struck Nawiliwili, Kauai, at 1:35 a.m. the next day, said Brian Yanagi, state Civil Defense earthquake and tsunami program manager.

If the warning centers in Hawaii and Alaska had deemed it dangerous, he said, Civil Defense would have sounded sirens and called for a statewide evacuation in late-night or early-morning hours.

However, Chip McCreery, director of the Pacific Tsunami Warning Center at Ewa Beach, said data from a pressure sensor on the ocean bottom off the Aleutians, coupled with tidal information, showed the tsunami was not a threat.

The Alaska warning center issued a tsunami warning for its region because of the size of the earthquake, then canceled it, he said. Hawaii was under an advisory.

"We were watching the situation very carefully here," McCreery said. "The thing very exciting for us was, when the buoy data came in, basically it confirmed the way we were leaning already based on coastal data."

"It all worked the way it was supposed to work," said Eddie Bernard, director of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Pacific Marine and Environmental Laboratory in Seattle.

Bernard, former director of the warning center at Ewa Beach, worked many years on development of the Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis system.

The National Data Buoy Center is operating the system of six surface buoys with bottom pressure recorders that send real-time data to satellites on water level changes.

Tsunami scientists call the instruments "tsunometers," similar to seismometers monitoring earthquakes, Bernard said.

Three are in the Gulf of Alaska, one of the most dangerous spawning areas for tsunamis in Hawaii. Two are off the Oregon coast. Another buoy is south of the equator off Chile, another hazardous tsunami path toward Hawaii. Chile has purchased a seventh buoy to add off its coast.

Bernard said it was exciting to see the detection system "making a difference" as he had envisioned.

He estimated the total cost of developing and installing the detection buoys at about $10 million. By contrast, he figured the data saved Hawaii $60 million to $70 million in lost productivity if an evacuation had been called after the November quake.

McCreery said the system is expected to have 20 sensors when completed in 2011.

Besides reducing warnings for nondestructive tsunamis, the system, it is hoped, will help identify shorelines most at risk from tsunamis and provide information on which waves might be the largest and the times of their arrival, he said.

A forecast model developed in Bernard's lab predicted what the reading would be on the gauge in Hilo Harbor after the November tsunami, and when it arrived in the middle of the night, "it matched very well," McCreery said.

The wave was about 1 foot from the crest to the trough of the wave, he said. "The nice thing is, it (the prediction) matched the cycles of sea level going up and down for several cycles of wave. That's a very good thing.

"If we could guarantee we'd have that kind of information and it would be accurate, it would be extremely useful to know."

For example, in 1960, when a tsunami spawned by a big earthquake in Chile killed 61 people in Hilo, the first two waves were quite small, he noted. People went back to the coastline in the middle of the night after a long evacuation, thinking it was safe, he said.

But, he said: "The third wave was quite large. With this kind of modeling, our hope is we'd be able to tell them a third wave would be large and when it would arrive."

Although the centers receive data from ocean floor instruments within minutes after it is recorded, "the tsunami has to propagate from the source to the gauges," McCreery said.

"We want to put more of these out so for any particular earthquake we don't have to wait too long for a tsunami to propagate to the nearest gauge."

Yanagi said there are too many gaps between the buoys in the Aleutians for adequate coverage. He said 20 to 30 buoys are needed "to have a robust system."

Better coverage also is needed off Japan and the Kamchatka Peninsula, where tsunamis destructive to Hawaii have begun, he said.

But Yanagi said "tremendous strides" have been made in quickly detecting an earthquake and measuring the size, intensity, depth and rupture zone.

While research has paid off in reducing unnecessary alarms and evacuations, Hawaii residents must be aware they live in a hazardous area for tsunamis and earthquakes, Bernard emphasized.

"When it's appropriate, we will evacuate people," he said.

— ADVERTISEMENTS —

— ADVERTISEMENTS —