ASSOCIATED PRESS

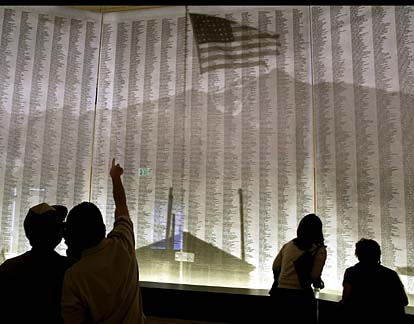

Visitors searched for their names and those of their relatives on a list of internees yesterday during the opening of the Manzanar National Historic Site about 220 miles northeast of Los Angeles. The site was an internment camp during World War II.

Japanese internment

museum opensThe site features photos,

films and documents regarding

life for the detainees

MANZANAR NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE, Calif. >> Like many Japanese Americans interned in the wind-swept Owens Valley during World War II, Towru Nagano remembered the desert sun, swirling dust and glare of searchlights that kept prisoners awake at night in cramped barracks behind barbed wire.

WW II internment

Facts about the World War II internment of Japanese Americans and the Manzanar National Historic Site:>> In 1942, amid fears of sabotage after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government ordered the relocation to detention centers of about 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry living on the West Coast.

>> The detainees were confined at 10 relocation centers in seven states: California, Arizona, Idaho, Utah, Wyoming, Colorado and Arkansas.

>> The Manzanar Interpretative Center, 220 miles northeast of Los Angeles, includes 8,000 square feet of exhibits, two small movie theaters, a bookstore and park offices.

Source: National Park Service.

Mostly, he recalls the realization that his country didn't want him.

"The worst part of camp was the psychological effect of being rejected by the public as an American citizen, as an equal," Nagano said yesterday while visiting his former internment camp under happier circumstances.

Nagano, now 78, was among hundreds of former detainees and their descendants who traveled to the Manzanar National Historic Site for the opening of a National Park Service museum that preserves a bitter memory for many Japanese Americans.

Manzanar, a Spanish word meaning apple orchard, is the best preserved of the camps where thousands of Japanese Americans and citizens of Japan were held during World War II.

The center features photos, films and documents that record the roundup of men, women and children amid racial prejudice and fears of sabotage and espionage following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

The $5.1 million museum is set amid the backdrop of the peaks of the eastern High Sierra about 220 miles northeast of Los Angeles.

The exhibits take visitors through the background behind the government order to detain about 110,000 people. It details life at the detention centers and tells of the gradual release and the official apology signed by President Reagan in 1988.

Yesterday's opening coincided with the 35th annual pilgrimage to the site by Manzanar inmates and their families. Many visitors searched for their names and those of their parents and grandparents on a list of internees that stretches nearly to the 17-foot high ceiling of the museum.

Louis Watanabe found the name of his grandfather, who worked as a stonemason and handyman while detained.

"I think it's important to talk about history so maybe we don't repeat mistakes of the past," Watanabe, 47, said as visitors milled about before a ceremony that sought to blend patriotism and an embrace of Japanese culture. Featured were a Taiko drum group and the presentation of the colors by the Veterans of Foreign Wars from the nearby town of Lone Pine.

The museum, and plans to restore portions of the camp, reflects the National Park Service's effort to appeal to what it calls "heritage tourism," or sites that may evoke painful memories. Other examples include agency projects in Minidoka, Idaho, location of another internment center, or the spot where Flight 93 crashed in Pennsylvania on Sept. 11, 2001.

"We learn as a nation and we grow as a nation from stories that are not always the positive stories. We've got to tell both sides," Fran Mainella, director of the National Park Service, said after the ceremony.

At its peak, Manzanar held more than 10,000 people. About two-thirds of all those interned there from 1942 to 1945 were American citizens by birth.

The camp had many aspects of a city, with schools, churches, temples and even a newspaper. Many younger detainees have fonder memories than their elders.

"We used to sneak under the fence and go out to the hills as far as we could go," said Itsu Iwasaki, 70, of Orange.

Toshiko Tanner of Lakeland, Fla., was 8 when she arrived at Manzanar. Her sister, Sekiko Kawasaki, was 13. Yesterday, they ticked off a list of unpleasant memories, including bad food, lack of privacy, a straw mattress and scorpions that would crawl into their barracks. Neither expressed bitterness.

"Because of that, we can stand anything," said Kawasaki, who lives in Los Angeles.

— ADVERTISEMENTS —

— ADVERTISEMENTS —