Special-ed spending

sees jump since ’94The Felix decree spurs the state

to create a comprehensive system

Over the last decade, spending on special education for Hawaii's public school students has nearly quadrupled as the state forged a new system under federal court order to serve students with disabilities.

A lawsuit filed in 1993 on behalf of student Jennifer Felix has helped transform Hawaii's approach from one with little money and few services for special-needs children to a comprehensive system for identifying and helping them, inside and outside the classroom.

"When I took the case on 11- 1/2 years ago, parents of autistic children had nowhere to go," U.S. District Judge David Ezra said in court on April 8, as he approved a plan to end court oversight of special education next year. "The students were typically put in a corner or expelled from school. That kind of thing doesn't happen anymore."

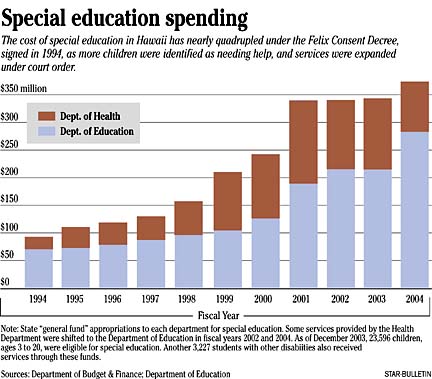

The change has come at substantial cost. Special education accounted for $284 million in general fund appropriations to the state Department of Education this year, a nearly fourfold increase over the $75 million spent in the 1994 fiscal year, according to figures kept by the Department of Budget and Finance. The Health Department's special-education budget has also shot up, to $89 million from $22 million.

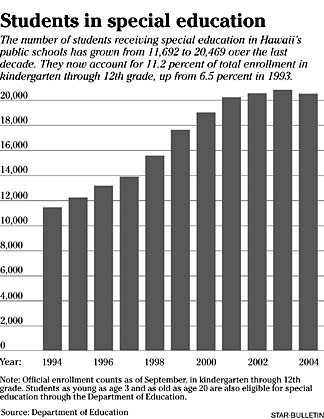

Meanwhile the number of children, aged 3 to 20, receiving special education or services for disabilities has climbed to 26,800 last December, or nearly 15 percent of the student population, from about 13,000 or about 7 percent in 1994.

"I want to acknowledge the tremendous change that has occurred," said Shelby Anne Floyd, a plaintiff's attorney. "We have much more timely identification and program development, and we have a very large increase in funding, which is necessary to provide services required by the law. These are huge gains for the children we represent."

Spending on regular-education students in Hawaii's public schools has increased at a much slower pace than special education. Appropriations for "instructional services" for regular education went up 62 percent over the decade, to $977 million from $601 million in 1994, according to Budget and Finance figures.

Special education now accounts for about 22 percent of the public schools' overall budget for "instructional services," which include salaries and most school-based spending for all children. That's twice the slice of the pie it represented in 1994.

"It makes you wonder whether there should be a lawsuit on behalf of the regular-education kids, too," said Jocelyn Marquez, who worked as a student services coordinator at a public elementary school until December and is now a Realtor-associate with Eric Watanabe Realty Inc.

"If we're putting that much money into special ed, we should be doing that for the regular-ed kids, too," she said. "Perhaps the solution could be that parents help pay for some of the costs. At least that way, you know parents are willing to invest in their own children's needs. We created a black hole when we didn't take care of the Felix kids, and now we're paying for that."

The Felix suit contended that the state was violating federal law by failing to provide appropriate education and mental-health services to children with disabilities. A consent decree signed in 1994 set out benchmarks for improvement by the state.

Spending took a big jump after the state was found in contempt of court in 2000 for failing to meet those obligations, but is leveling off somewhat. In recent years, programs such as school-based mental health and autism services have been transferred from the Health Department to the Department of Education, boosting the public schools' portion of the special-education budget.

"There was significant underfunding when Felix started," said Robert Campbell, director of program support and development in the office of the superintendent. "The reason for that early spike in costs was basically putting together the infrastructure necessary that had not been there early on. We had some catching up to do."

He added: "In terms of costs, we generally follow the national pattern. We're not the only state or district dealing with 'Boy, this is costing a lot!'"

Across the country, schools spend twice as much, on average, on each special-education student as they do on each regular-education student, according to a study funded by the U.S. Department of Education entitled "What Are We Spending on Special Education Services in the United States?" published last year.

The largest category of students in special education in Hawaii are those with learning disabilities, followed by those with emotional disturbances and developmental delays. Some observers say too many children are being classified as learning-disabled, in Hawaii and across the country.

"It's no longer a system of education -- it really should be called a system of education and a system of care," said Sue Parry, an occupational therapist who owns a consulting business called ADD Watch Hawaii. "With special needs, anything goes."

She added: "Some children need therapy, but is that really the job of the school to provide that? What about the kids that don't have any problems? The money's being sacrificed for these other programs."

Ezra said he pushed the state as far as he could to provide for special-needs children, without detracting from funding for the general student population. He called the case the toughest of his career, because everyone has a different idea of what constitutes an appropriate education.

"I have tried to take a measured approach that the state has an obligation to provide a free and appropriate public education, not just to members of the Felix class but to all," he said. "I could not compel the state to provide so much in one year that it would essentially cut off public education for other students."

An array of staff has been put in place across the state, including teachers recruited from the mainland, educational aides, school psychologists, speech pathologists and case workers. Students with severe problems also qualify for assistance outside of school hours to help them develop skills at home.

Jill Park of Kaneohe says her autistic 9-year-old son, Dustin, has made great strides with help from a skills trainer under contract with the Department of Health, but she's worried about his future.

"He's come so far," she said. "He's progressing and he's mainstreamed." She wiped away tears as Ezra approved the plan to end court oversight in June 2005, explaining afterward that she fears that such personalized services will be cut back by the DOE because of the cost.

Plaintiff's attorney Eric Seitz said he hears daily from parents of children who are now thriving despite serious disabilities. In the last school year, the system performed acceptably for 91 percent of youth reviewed, according to a January monitoring report issued to the court.

Seitz said the mental health and other personnel hired as a result of the lawsuit ultimately help all public school children.

"We all benefit from them, not only those who receive services directly," Seitz said. "One reason why we brought this case was that we believed that by addressing the needs of the most needy children in public education, we could improve the system as a whole. I think that's happened."

Hawaii's Comprehensive Student Support System, which is tallied as special-education spending, also serves regular-education students. It can catch behavioral problems early and help prevent costlier intervention and referrals to special education later, Campbell said.

He noted that federal law does not demand that the school system "cure" a student's learning disability. "It requires us to make sure that the student has all the support necessary to benefit from educational opportunities like other students," he said.

"We are always trying to do it more cost-effectively, but the truth is, special education does cost more," he said.

— ADVERTISEMENTS —

— ADVERTISEMENTS —