Court scales back

oversight of special education

U.S. District Judge David Ezra approved a plan yesterday to end court oversight of special education in Hawaii's public schools, more than a decade after disabled student Jennifer Felix sued the state for failing to give her an adequate education.

"The law does not allow me to maintain jurisdiction until the state gets it perfect," Ezra said, agreeing to reduce court oversight under the Felix Consent Decree in anticipation of dismissing the class-action case in June 2005.

He said the state is in "substantial compliance" with federal law, which requires a free and appropriate public education for all children, and described Hawaii's special-education system as now better than the national average.

"We have met the obligation to our students to build a system of care that delivers quality services in a timely manner," said schools Superintendent Patricia Hamamoto.

She added that she is committed to sustaining that effort.

The state will post quarterly performance reports on the Internet with school-specific data, and plaintiff attorneys may raise concerns with the court for the next 15 months, under the agreement approved by Ezra.

The jobs of the Felix special master and court monitor now end, along with the state's obligation to pay for plaintiff attorneys' fees and costs.

"This court is not abandoning this case, nor am I abandoning the children," Ezra said, adding that he insisted on extending court oversight through next year's legislative session to ensure that adequate funding and services continue.

Felix, who contracted a viral infection as an infant and suffers from seizures and brain damage, was 20 when the suit was filed in her name in 1993. She is currently in the hospital, and her mother, Frankie Servetti-Coleman, was unavailable for comment, according to their attorney, Eric Seitz.

Servetti-Coleman sued the state on Felix's behalf, saying it was violating federal law by failing to provide appropriate educational and mental health services.

The Felix Consent Decree was approved the following year, setting out benchmarks for improvement by the state.

In May 2000, Ezra found the state in contempt of court for failing to meet those obligations, but services have ramped up since then.

"We have made enormous progress," Seitz said. "We now have a system dramatically different than the system we had even five or six years ago."

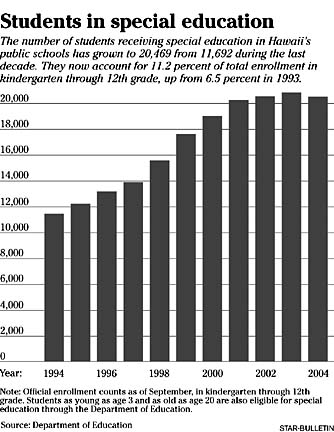

The number of students in kindergarten through grade 12 in special education has grown to 20,469 as of September, up from 11,692 in September 1993, according to the Department of Education. They account for about 11 percent of total enrollment, up from 6.5 percent in 1993.

The department is also responsible for special-needs children as young as 3 and as old as 20. An early intervention program run by the Department of Health works with children from birth to age 3.

Some parents who attended the court session said they were concerned that services for their special-needs children might suffer without the hammer of the court hanging over the state.

"People in remote areas are worried that as soon as the court monitor pulls out, they're gong to be left out to dry," said Susan Boyd, who lives in Kau on the Big Island and has a 16-year-old son with an emotional and behavioral disorder.

— ADVERTISEMENTS —

— ADVERTISEMENTS —