COURTESY OF NAJEE LYNNE

Stringing it out

The qualities of a bass

and sitar are combined

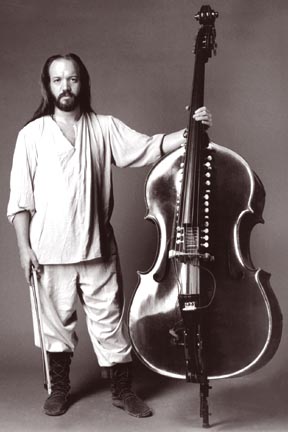

The photo on this page says it all: A serious-looking Mark Deutsch holding the curious instrument of his own creation, dubbed the Bazantar (emphasis on the second syllable).

Patented back in the late 1990s, Deutsch's Bazantar is a 5-string acoustic bass that's fitted with an additional 29 sympathetic strings and 4 drone strings. Considering his background as a classically trained player of the bass -- and later a student of the sitar, taught by the great Ustad Imrat Khan -- that it's no surprise that this intellectually restless musician took it upon himself to make such a unique instrument that combines the best qualities of both.

Mark Deutsch

The 3rd Biennial Hawaii Contrabass FestivalWhere: The Doris Duke Theatre, Honolulu Academy of Arts

When: 7:30 p.m. Tuesday

Tickets: $22 general, $15 students and seniors

Info: www.cbfest.org

Note: Barre Phillips' "My Town, Your Town" will share a bill with improv solo bassist Tetsu Saitoh 7:30 p.m. Wednesday at the Paliku Theatre, Windward Community College. Ticket prices are same as above.

Still, "it's almost like 2 different instruments, depending if I pluck or bow it," he said by phone from Maui earlier this week, where he was guest teaching. "The bowing, some way, makes it sound more melodic -- but plucking it can be extremely melodic as well. But if it's something jazzy or bluesy, I pretty much pluck it to maintain a steady groove or rhythm. But it can also sound pretty ethereal when I use a bow."

(Deutsch and his Bazantar return for a concert Tuesday at the Honolulu Academy of Arts' theater, as part of the weeklong 3rd biennial Hawaii Contrabass Festival. Both made their debut at the previous festival.)

In talking with Deutsch, one can tell how he tries to strike a fine balance between his art and his thought process. Even though he melds his interest in non-linear mathematics, sacred systems and cosmology into his music, it's his intention to make it sound all seamless.

But even though he started playing professionally at age 12, please don't call him a prodigy.

"It didn't mean I was good at that age," he said. "My uncle and my dad were both pros themselves. I thought my uncle was pretty good, and even though my dad had a band, he was not a naturally gifted musician ... he was more a fine artist. But even at age 9, I knew I wanted to be a musician. ... I remember when I first heard music, it was the ultimate magic, so emotionally intense and intellectually disorienting. It was hearing Cat Stevens' 'Wild World' in the 5th grade, 'Knights In White Satin,' the Beatles -- just having no idea what it took to make those sound.

"But it took a lot of work. I admit I built my skills from the bottom up. ... I was taught all my life that, while being gifted can be great, it's will that is the ticket."

DEUTSCH ADMITS that once his Bazantar came under the scrutiny of his fellow players, they weren't all that accepting of it. One who was on his side, however, was Barre Phillips. The expatriate jazz and improv master will also be performing at next week's contrabass festival, playing a theatrical piece -- complete with masks -- entitled "My Town, Your Town."

Corresponding via e-mail during his minitour of his adopted home country of France, Phillips briefly described his work as both "a reflection on my interior sound world and how to bring it out into the light" and "a look at the two distinct sound worlds of the French Provence, where I live, and Japan, where I've often traveled, and their effect on me as a a musician."

It's this quality of pushing the envelope that appeals to Deutsch as well. The San Francisco resident has collaborated with other genre-blurring musicians like himself, plus played with master didjeridu player Stephen Kent, and is planning to play with a Balinese gamelan orchestra.

All this thanks to a dream during his studies with the legendary North Indian classical master.

"When I was studying sitar with Ustad, he claimed it took those with Western ears 20 years to master it. I didn't buy it, however, so to help me, I was listening to Indian music in my sleep, and one night, I was dreaming I was playing bass but hearing the serangi, with its sympathetic strings."

After patenting the design of his Bazantar, Deutsch said over a three-year period and going through a couple of prototypes, he finally, in late 1997, built an instrument stable and resonant enough to satisfy him.

"I finally knew I got it, and I always believed I could do it," he said. "It took a lot of years of spending all my time and money ... but, after a week I knew it was coming in, then after a month, I thought 'man, this keeps getting better than I hoped,' and now it's super sweet, with a better integrated sound."

Deutsch admits that the Bazantar "has kicked me into a completely other place musically," utilizing elements of Indian and Western classical music, jazz -- and organic physics -- into his approach of what he calls "composed improvisation."

In concert, he says he akins his time on stage as "being out there on a tightrope. I don't know beforehand how or what I'm playing. ... It's something that I like to hear in other musicians, being on the edge and also having an excellent organizational ability. That's what I strive for -- giving the audience a moment of creation."

And, by the way, Deutsch is developing both a more marketable and less expensive version of his Bazantar, plus something called a Cellantar, jumping off the basic design of a cello.

Click for online

calendars and events.