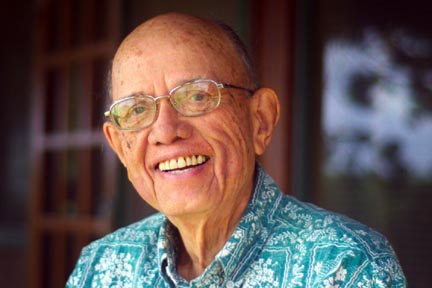

RICHARD WALKER / RWALKER@STARBULLETIN.COM

Ka'upena Wong is among five musicians who will be honored Sunday with Hawai'i Academy of Recording Arts 2004 Lifetime Achievement Awards.

Life’s passion

Ka'upena Wong will be honored

Sunday for lifelong commitment to

making music and promoting an

evolving Hawaiian culture

There are many people in Hawaii who actively seek out public honors and awards, but Ka'upena Wong isn't one of them. When Wong learned that the board of governors of the Hawai'i Academy of Recording Arts had picked him as one of this year's five recipients of HARA's Lifetime Achievement Award, his first response was to decline.

"I was flattered (but) I was totally surprised. I was really taken aback. I wanted to withdraw my name," Wong said earlier this week as we talked about the ceremony coming up on Sunday, when HARA honors Wong, Kawai Cockett, Bill Kaiwa, Peter Moon and Marlene Sai during a nontelevised luncheon show in the Maui Ballroom at the Sheraton Waikiki.

The proceedings will include musical performances -- maybe by the honorees, maybe by their students and protégés, and maybe some of both. Last year's event included a performance by award recipient Buddy Fo and performances by "Uncle Bobby" Moderow, of Moanalua (honoring his former mentor, Raymond Kane), and steel guitarists Alan Akaka, Greg Sardinha and Casey Olsen (honoring steel guitar legend Jerry Byrd).

To be honored

Hawai'i Academy of Recording Arts 2004 Lifetime Achievement Awards:Where: Sheraton Waikiki Hotel Maui Ballroom

When: 11:30 a.m. Sunday

Tickets: $55 includes lunch

Call: 235-9424

Video clips honoring this year's five recipients will be screened and then recycled when HARA presents the 2004 Na Hoku Hanohano Awards in May.

HARA's Lifetime Achievement Award is the ultimate prize bestowed by members of Hawaii's local record industry, and is the successor to the Sydney Grayson Award for lifetime achievement when the Hoku Awards were created in 1978. HARA changed the name of the prize in 1987, which also marked the first year that more than one person was honored. Multiple awards have been the rule ever since, as if to make up for lost time. As of 2002, HARA hands out five awards each year for lifetime achievement in the local record industry.

WONG'S MODESTY is endearing but his award is well earned. He has been recognized as the most renowned male chanter of his generation, and gained his command of the language through 12 years of study with Mary Kawena Puku'i, an authority on Hawaiian culture and language who co-wrote the Hawaiian Dictionary with Samuel H. Elbert. Wong also studied hula and the Hawaiian musical instruments that are associated with the dance.

Three landmark performances as a chanter are representative of his accomplishments: the 1964 Newport Folk Festival, the dedication of the Kamehameha statue in Washington, D.C., and the launching of the Hokule'a. He has also contributed to the preservation and perpetuation of Hawaiian culture as a teacher, recording artist and Hoku Award-winning liner notes writer.

"You get a gig, you do the gig and then you say 'so long,'" is how he describes his career as a performer, teacher and writer, explaining that his studies were a quest for knowledge rather than fame.

"I studied (these things) to fulfill my own self in terms of our Hawaiian heritage ... and if I moved on by sharing it with others, that wasn't really a major thought, but if it happened, I was pleased to do it. I needed to ask questions of my sources so that I could be more enriched by what I felt was a wonderful culture that all of us can aspire to and enjoy."

Although many speak of the recent past as a time when Hawaiian language and culture were suppressed in favor of fluent English and "haole culture," Wong said he feels that hindrances to learning might also have been credited to a lack of interest.

"I feel -- to use a polite word -- 'challenged' when I hear comments about 'this was pushed aside' or 'that was pushed aside.' I think that if you were interested (in learning), you'd really find out that it wasn't being pushed aside. It was there, it was just a matter for us to tap into it and move on from there. Enrich yourself and move on."

"This is not to say that in the history that was before (my time) that there wasn't this squelching of aspects of Hawaiian culture, but I never felt that it was being oppressed. There were always people like some of my teachers, and they were there. And also there were others who said, 'This is part of my Hawaii, too' -- I hate to use the term 'non-Hawaiians' -- who felt very strong about the original aboriginal heritage ... and wanted to enrich themselves by studying it. I'm very grateful to them, too."

RICHARD WALKER / RWALKER@STARBULLETIN.COM

WONG SAYS THAT at 74 he is continuing to read, search, study and "think about" Hawaiian music.

"It's a major cultural power in our islands, and it will always be with us. I don't feel threatened with it being lost. There is this in-depth rhythm of Hawaiian music, hapa-haole, chant (and) the Hawaiian music of the Charles E. King type that's a part of our lives.

"It's just part of our island makeup ... not only the rhythm of the music that permeates these islands, but where individuals and groups take it and re-create it or deliver it as they have heard it."

He mentions the Brothers Cazimero, Makaha Sons and Na Palapalai as examples of younger musicians who "are interested in Hawaiian music ... and have taken the time to enrich themselves and to become informed so that when they do a delivery of a song, it's really quite lovely.

"I am just thrilled with some of the music I'm hearing from some of these groups ... and then also I'm delighted by the 'Na Mele' series from public television. For an old buck like me, (these groups) make a connection to the past and (people) like Lena Machado, George Kainapau (and) Johnny Almeida."

Unlike some modern observers and scholarly types who dismiss hapa-haole music for representing a form of cultural colonialism or bastardization of Hawaiian culture, Wong says such music is, in fact, another part of "our ethos, our musical selves."

"It gave pleasure to people in the '20s and the '30s. It gave pleasure to (people of) my vintage in the '30s and '40s, and we can't deny it. It's there and it's part of our ethos, and it's truly a native music. ... It's very much a part of our lifestyle and our own musical profile. I can't see us not having it.

"I'd still like to see (young Hawaiian acts) tap into the music of Sonny Cunha and Johnny Almeida, but it will come, because what I'm hearing now (shows me) that Hawaiian music is alive and well, and I just take my lau hala hat off to them (because) they've taken a position of wanting to preserve and to perform."

Wong says there is a bit of ego involved in performing, and makes it clear that he's speaking of himself as well as others when he says so. The important thing is that groups are "moving on beyond their ego to come up with some very creative and enjoyable music and presentation.

"The music is changing but there is an element, a continuity, that prevails, and I think it's that continuity that these new groups and these young groups have absorbed and then presented in their own way. The music is changing, but we shouldn't feel that we are losing the music ... and being a non-native speaker should not inhibit anyone from trying to pursue the art of Hawaiian music."

Click for online

calendars and events.