|

First Sunday Mark Coleman |

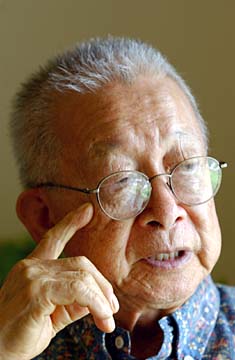

RONEN ZILBERMAN / RZILBERMAN@STARBULLETIN.COM

Since his wife, Lynne, died in 1997, one of the Rev. Mitsuo Aoki's morning rituals has been to touch her photograph on his living room wall and speak to her briefly. "Whatever crosses my mind, I tell her," he says. "Then I tell her, 'Saturday, your turn to talk.'"

Taking the next step

Death has been no stranger to us at the Star-Bulletin recently. A week ago, the 5-year-old daughter of business reporter Allison Schaefers drowned in a shocking accident. A few weeks before that, our longtime three-dot columnist Dave Donnelly died at age 66. And during the past year, veteran copy editor George Steele also died. He was 56.

Were their deaths bad things? Yes, of course, for those of us who mourn their absence. But if you view death as merely a passage to a new stage of life, perhaps the answer is no. That is the view of the Rev. Mitsuo "Mits" Aoki, who in his 89 years has counseled hundreds of terminally ill individuals, both in person and through a 2003 video called "Living Your Dying."

Aoki came to his beliefs as a Buddhist in his early years, growing up in a Japanese camp on a Big Island sugar plantation, then as a minister after converting to Christianity in his mid-20s. After church service in Hawaii and academic training here and on the mainland, Aoki helped create, during the late 1950s, the University of Hawaii Department of Religion, where he taught nearly 40,000 students before retiring about 10 years ago.

In 1979 he co-founded Hospice Hawaii, which helps terminally ill patients live as comfortably as possible during their last months of life. He also established the Foundation for Holistic Healing, which promotes a holistic approach to health and dying.

Once active in Tai Chi, Aoki has slowed down a bit during recent years, but still keeps busy socially at Pohai Nani Retirement Community in Kaneohe, where he has lived since 1993.

In January, Aoki was named a "Living Treasure of Hawaii" by the Honpa Hongwanji Mission of Hawaii.

The continuity of life

Mark Coleman: A friend recently asked me, "If you had one super power, what would it be?" I thought about it for a day or so, then decided it would be to fly.Mitsuo Aoki: I think everyone has the fantasy to do something like that.

MC: I also thought being strong would be nice. And then, also, to never die.

MA: (Disapproving nod). You ever thought of that?

MC: Well, I thought about it briefly in terms of whether that qualified as a super power, and second, if it's something I'd want to do. But of course, you think dying is a continuation of something, right?

MA: Sure, it's a process. Like everything else in this world. Whatever emerges will always die. It's part of the process of life itself.

MC: So it's an energy force that re-emerges somehow?

MA: I think so. It's not a tricky thing. From ancient times -- the mythologies and legends -- you always have something called heaven. Simply, that is a metaphor for the continuity of life.

RONEN ZILBERMAN / RZILBERMAN@STARBULLETIN.COM

"(Death is) amazing. It collaborates with life in such a way that it seeks to push you to the more ultimate next step." --The Rev. Mitsuo Aoki, Co-founder of Hospice Hawaii and longtime counselor to the dying

'Live our dying'

MC: When people who are dying come to you, do they often expect some answers you can't give them?MA: Yeah. See, I've been in this business over 40 years, teaching at the university and all that; I helped create the hospice movement, things like that, so there's lots of expectation when people call me. However, my way is to say, there's so much in life that I don't really understand or know, and yet, because of my life with God, I feel that in some amazing ways, somehow God gets into those spaces where I don't know much, and he manifests to me what that space is about -- the space of cancer or whatever it is. So somehow, because of my life with God, I'm able to talk to a person who's dying, and when they tell me they're afraid of this or that, instead of giving an answer for their fear, I try to urge them to step into the fear and go another mile with it.

MC: When talking to people who are dying, what's the general feeling that usually happens: calmness, honesty or panic?

MA: No, what happens is the difference between my approach and other people's approach, because of course I think of death as the end of life and all that, but alongside that is a more powerful imagery, which is that death is really that great kind of energy that helps an individual to touch the depth of their humanity like nothing else can.

My wife (Lynne) is a classic example. Cancer had metastasized through her whole body, and the doctors said she had a short time to live. She actually went on for seven weeks after she came home. But she told the doctors, "My husband and I are going to go home, and we are going to live our dying." That's the expression I've been popularizing -- "live your dying" -- and she lived her dying for seven weeks. Amazing thing.

Now, in my work, usually by the third week, I help the person let go -- put in the past all the unfinished business. So my wife decided to let go. We took our photographic albums, she went through each one. Anything she saw of somebody and some unfinished business, she finished it, saying "I wish I could have done this" or whatever.

But then she came upon a photograph of her first husband (to whom she had been married for 23 years). She didn't have much energy, but boy, the energy that came out. It was anger that developed into angst, and it lasted for about six minutes. Then there was an amazing silence. I thought, "What the heck's going on?"

Then, she turns to me and she says, "Sweetheart, I experienced an amazing sense of forgiveness; I felt God has forgiven me." Then, to my amazement, she turns to the photograph (of her first husband), calls him by his first name and says, "I want to share with you the forgiveness I have now experienced at my death." We had been married for 27 years, and I had thought she already had let go of any anger she might have had toward her first husband, but she hadn't. It took death to really allow her that extra step, and when she did that, something in life emerged through the anger and emerged as forgiveness.

See, that's the role of death. I've worked with over 900 dying people over the past 44 years and I can tell you, with half of them there is a minimal time in which they learn to forgive so easily. They learn to express love. Their sons and daughters say they never heard dad talk about love, but now he's talking about love. Not on a deep level always, but anyway, they're going across that threshold, and you can only say it was the context of death that allowed them to go through that experience. So that's what I'm trying to say about death. It's amazing. It collaborates with life in such a way that it seeks to push you to the more ultimate next step.

Near-death experiences

MC: Those are situations where the person is aware they're dying. What about situations where it's a surprise, like someone who dies in a car crash?MA: That's a different story. That's very difficult. All you can do is console the family. The person was killed, they're gone.

MC: But what do you think it means for that person? For example, when you had your car crash (in 1960), you had an out-of-body or near-death experience.

MA: Right. I think for a great many people, from what we know now, this near-death experience is a natural phenomenon. It happens all over the world.

MC: And when you don't get called back for whatever reason, you go on?

MA: That's right.

MC: What do you think happens then?

MA: Well, I've read about at least a hundred books on this subject, because this is my work, and the dominant feature of these near-death experiences is that nearly every person meets a person they call a "Being of Light." It's so brilliant, they cannot make out the features of the face. All they see is the light. But what they experience is awesome love, which emanates from that energy. And many of those who come back to life, instead of going away, that love permeates them so much that in their mind they say, "Gee, if I can only manifest that kind of love when I go back," and when they say "I want to go back," that's when they come back.

RONEN ZILBERMAN / RZILBERMAN@STARBULLETIN.COM

The Rev. Mitsuo Aoki, who served on former Gov. Ben Cayetano's blue-ribbon committee on physician-assisted dying, says the "death with dignity" bill should be passed.

The image of death

MC: There's a great quote I came across recently by writer Peter Barton: "There's nothing more humbling than an awareness of death. Death is the opponent that every single one of us will lose to. It's not a pretty fact, but once you get it through your head, you begin to live more honestly."MA: But that image of death is still very faulty.

MC: Why, because you think he's saying that after death, that's it?

MA: Well, you just read it: "... that every single one of us will lose to."

MC: Well, maybe it's definitional, because when you die, that chapter of life really ends. Yet you say, overall, that life continues. Is there an element of faith regarding what you're talking about?

MA: Yeah, there is. But you see, the image of death is still based on this (that life ends at the time of death). So for the medical profession, up to today, they do all kinds of technical things for a patient, but when the person dies, they consider it a failure on their part. Failure, mind you. It's a very strong feeling among many doctors. There's a point that death is almost an enemy that's going to mow you down. And the image we have, you know, it's of the man with a scythe.

MC: The Grim Reaper.

MA: Exactly.

MC: And he's not very attractive or happy looking.

MA: That's right. So the work I'm doing, basically, is to change the paradigm. It's a very difficult thing to do.

MC: What about agnostics? The scientific method prevents an agnostic from committing to the idea of afterlife or anything you can't prove physically. What do you think about that?

MA: Well, that's a freedom. (Laughter)

Life after death

MC: If you think there is life after death, so to speak, do you think that we return to this material world? And if so, in what form? Like, do we come back as cockroaches, if we were bad?MA: Well, those things (bad behaviors) are a part of the fabric of the process of life itself.

MC: Do you think you lose all memory of this stage of life?

MA: Again, I don't try to explain. Essentially, the metaphor is nature. A famous poet, I forget his name, said, "I become part of the sunrise and the sunsets and the air that blows through the Pacific." You become part of life, in terms of nature. Natural.

MC: Do you feel like we're surrounded all the time by the beings that went before us?

MA: Yes. I think so. There's something called the energy of life. The word is "spirit." And that spirit is not just within you. It's the spirit that permeates all of creation. There is a form of energy that is inexhaustible, eternal.

The politics of death

MC: Do you think there should be laws against suicide?MA: No.

MC: What about physician-assisted death?

MA: I served on the blue-ribbon committee concerning that issue and we were all agreed, essentially, with a few dissents, that we should pass that bill. It has lots of safeguards within it.

MC: What is the death-with-dignity movement about?

MA: It's really about trying to help a dying person die with the most human elements possible.

MC: Is Hawaii a good state in terms of how people who are dying are handled?

MA: Yes. One of the things I'm grateful for is, since four years ago, every incoming freshman at the University of Hawaii medical school takes a year doing hospice work, which is fabulous.

MC: Do you think that federal drug laws are interfering with pain control?

MA: The terrible thing with (President) Bush in this last pronouncement about drugs, he weighs too much emphasis on the pharmacologists and less on the so-called people, so people still have to go to Canada to get the good rates on pills and drugs.

MC: Is there a problem here with access to pain control?

MA: No. What we see happening is, the hospice has been working very effectively for the last 30 years now, and in those short 30 years this whole philosophy of caring has permeated into the medical community. What is now emerging is what they call palliative care (treatments that alleviate pain without curing the disease). You can be massaged, meditation, all that. It's a very different approach.

MC: Is that expensive?

MA: No. The joy is that it's the least expensive for the customers as well as for the hospital.

MC: Do you think the medical marijuana issue is relevant here as well?

MA: Yes. Anything that can help relieve the suffering of people should be looked at with sympathy and concern.

See the Columnists section for some past articles.

Mark Coleman's conversations with people who have had an impact on our community appear on the first Sunday of every month. If you have a comment or suggestion, please send it to mcoleman@starbulletin.com.