A forum for Hawaii's

business community to discuss

current events and issues

» Pricing psychology » Protect your computers

BACK TO TOP |

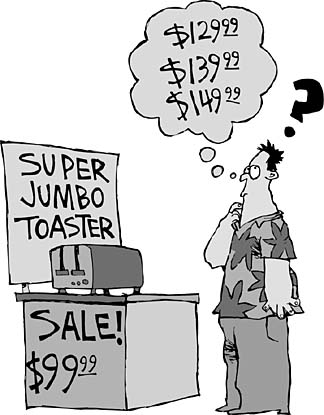

HOW DO WE RECOGNIZE A BARGAIN?

DAVE SWANN / DSWANN@STARBULLETIN.COM Pricing psychology

Despite what most people think, pricing is not just a matter of determining cost and adding some profit margin. There's a psychological component to customers' perceptions of prices that many businesses -- to their detriment -- do not consider. Customers react to a given price, and this is where psychology enters the picture. For example, let's look at one of the most basic customer reactions -- how we know a "good" price when we see it.

It can be said that every product has two prices: the actual price, or the amount of money that we have to give up to purchase the product, and a psychological "reference price," or what our mind tells us the product should cost. So every purchase decision involves a comparison between the actual price and our feeling about the usual price, or reference price. When the actual price is less than what we think the product "ought" to cost, we consider it a bargain.

Psychologists and marketers have assumed that we form these reference prices based on our memory of prices we have paid in the past for similar products. Interestingly, more recent research has shown that we, as consumers, don't really do a very good job of recalling prices we have previously paid. What we do retain in our memory is a certain familiarity -- an ability to recognize that a particular product's price falls within a familiar range. If I ask you to tell me the price you paid last time you bought a loaf of bread, chances are you won't recall the exact price. But if, while in the store, you see a shelf price of $1.59 for a loaf of bread, you probably recognize this as a good price.

It's also possible that we have no idea what a product should cost -- no previous experience with the particular product, and therefore no reference price in mind. We then turn to the advertised prices of similar or competing products to determine whether our product is "too expensive" or a "good buy."

Marketers may "help" us with our reference prices by pointing out to us which prices we should use in our comparison. A sign on the shelf that reads "Was $19.99, now $14.99" intends to establish in our minds that the product "should" sell for $19.99. Infomercials use a similar tactic when they ask "How much would you pay for this wonderful product -- $99; how about $79; or even $59? Now it can be yours for only $29.99."

Tips for business

Marketers can use this knowledge of psychological pricing to improve their marketing strategy:

>> Target your product toward customers who already have a high reference price. If you sell a $250 watch, try to advertise and position this watch so it appeals to those of us who typically pay $500 for a watch. If your watch seems to fit with our idea of what a $500 watch should be, the $250 price will appear to be a bargain.Businesses that fail to understand how we, as consumers, use reference prices to judge the appropriateness of a product's price may fall short of their full profit potential.>> Attempt to get customers to compare your product with an entirely different category of products. Vaseline did this by calling one of its products "Vaseline Lip Therapy" and suggesting it as a competitor to Chapstick, a product priced 14 times higher than regular Vaseline.

>> In the store, place your product next to products with which you would like to be compared. Don't put your gourmet coffee next to the everyday, less expensive coffees -- put it next to the gourmet chocolates and fruit baskets.

>> When introducing a new product, don't use a low introductory price to "get the ball rolling" and then hope to raise the price later. In our minds the low price will become the reference price -- what the product should sell for -- and subsequent price increases may fail.

>> Have you ever noticed how salespeople show us the most expensive house or car first? They're practicing "top-down" selling -- an attempt to make the next house or car seem like a better deal by establishing a high initial price in our mind. A research study found that a $28,000 car seemed less expensive when it was shown as part of a sequence of cars starting at $32,000 and going down to $24,000. The same $28,000 car looked more expensive when shown in a sequence of cars starting at $24,000 going up to $32,000.

>> Remember that having the lowest price is not as important as having the price fall within the reference price range that the customer expects to pay. If a woman expects to pay between $25 and $29 for a blouse, then the exact price of the blouse, as long as it falls within this range, is not as important as other product features such as fabric, fit and style. When it comes to less than $10 increments, many of us do not distinguish between price points -- a so-called "dead zone." If customers do not discriminate between a blouse selling for $28.75 and $29.95, then selling at the lower price can leave plenty of profit on the table.

>> Test your prices -- make a change and monitor the results. If you're selling a product for $26, try $28.95. If you find that customers perceive little difference with no drop in sales volume, then you're suddenly $2.95 better off per transaction.

Ted Haggblom is a marketing professor at Hawaii Pacific University. He is president of PriceLogic Corp. and a director of the Pacific Pricing Institute. He can be reached at 544-0831 or thaggblom@hpu.edu.

BACK TO TOP |

Inexpensive components

will protect computers

At the beginning of the year, I wrote a column on New Year's resolutions -- specifically, how to protect your data and secure your PC.

I know this topic has been covered extensively, but despite the repetition, many users still want to believe that bad things won't happen to them.

Don't kid yourself.

Although the likelihood of a terrorist attack in Ko Olina or Kakaako is pretty remote, as Murphy's Law dictates, things that can go wrong will go wrong.

You don't necessarily need Osama to spoil your day. There are plenty of nasty surprises such as flooding, power failures, fire, theft or other tragedies that can befall your home or business.

You don't have to spend a lot of money to ensure that your home business will weather trials and tribulations of biblical proportions. Rather than coaching you on preparing a disaster recovery plan, in the next few columns, I'm going to suggest some inexpensive technology that will ensure that if disaster strikes you can be up and running in short order.

There are some inexpensive ways to protect your PC from what we might term "everyday disasters." Chief among them are voltage abnormalities and loss of electrical power. Just as fatal are power losses (partial or total) caused by tripping over your power plug. (Hey, we've all done this.)

The best insurance policy you can buy is a UPS. I'm not talking about those brown delivery trucks. A UPS, or uninterruptible power supply, is a vital component of any home office. When the power goes out, the UPS switches on automatically, ensuring that your computers and network can run long enough for you to shut down your computer until HECO gets back on line. A home office model, which also acts to shield your computer from dips and surges in the electrical system, costs about $150.

A UPS comes in a variety of configurations, depending on your system's requirements.

UPS capacity generally is measured in battery life. Thus the more equipment (monitor, cable modem, etc.) you need to keep operating during an outage, the larger capacity you'll need. The rule of thumb is to get overcapacity, even if it costs more. The APC Web site (www.apc.com) has a good tool to determine the UPS system you'll need.

You can also purchase a UPS from companies such as Tripplite (www.tripplite.com), SL Waber (www.waber.com) and others.

The more sophisticated UPS models also have software that automatically saves files and shuts down your system. This works great in theory, but sometimes the software will collide with your existing system and cause it to crash. When you install your UPS, make certain that you test it by pulling the plug from the socket to see if it really shuts down the computer. Of course, make sure you save your documents before you do the test.

If you don't want to spend money on a UPS, at the very minimum get a good surge suppressor -- a device that acts as a buffer between your wall outlet and your computer. A surge protector redirects power surges through an alternate path of least resistance and protects your gear from extreme surges in voltage. In effect, it absorbs the voltage spikes and dissipates them before they harm your PC.

Surge suppressors eventually wear out, but the better quality ones have an indicator light that flashes when they have been damaged. If you are subject to frequent storms or brownouts, it's best to replace them every three or four years.

When purchasing a suppressor look for the "UL 1449" mark, which means that it's up to code with Underwriters Laboratories specs. Most suppressors will also list their joules rating, which is a way of telling how much of a surge the suppressor potentially can absorb. In general, the higher the rating, the better. I'd say purchase an absorber with at least a 300-joules rating. This will cost you in the range of $30-$50.

If you want to do more homework on protecting your gear from electrical abnormalities, go to HECO's Web site (www.heco.com), which provides useful tips and offers more ideas on purchasing surge protectors and UPS gear.

In our next column we'll look at how you can make sure your data is backed up properly so that in a worst-case scenario, you'll always have copies of your records.

Kiman Wong, general manager of Internet services at Oceanic Time Warner Cable, is an engineer by training and a full-time computer geek by profession. Questions or comments should be addressed to kiman.wong@oceanic.com

To participate in the Think Inc. discussion, e-mail your comments to business@starbulletin.com; fax them to 529-4750; or mail them to Think Inc., Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 7 Waterfront Plaza, Suite 210, 500 Ala Moana, Honolulu, Hawaii 96813. Anonymous submissions will be discarded.