Isle Asian kids lead

in reading and mathA report finds Filipinos and

Hawaiians trail other ethnic groups

A breakdown of public school test scores by ethnicity, released for the first time to comply with federal law, shows that Asian students in Hawaii scored highest on both math and reading at all grade levels tested.

Caucasians came next, placing consistently above the statewide average on the 2003 Hawaii State Assessment, while Hawaiians and Filipinos trailed the average. Test results show the same pattern in both subjects in grades 3, 5, 8 and 10.

The data were reported recently to the federal government as part of the No Child Left Behind Act, which mandates that states track the performance of all schools and various demographic groups at each school. The results largely reflect the socioeconomic status of the different ethnic groups, since poverty and immigrant status tend to depress scores, analysts say.

"There has long been interest in how different ethnic groups perform on achievement tests, and that interest is one that is widespread -- it's not just Hawaii, it's national," said Michael Heim, director of the planning and evaluation branch for the Department of Education.

"But ... there are other variables that go along with ethnicity that are highly correlated, such as socioeconomic status," he said. "Ethnicity is often a proxy for many other factors -- such as child nutrition, poverty, educational level of the mother and father -- that are more causal in terms of students' achievement."

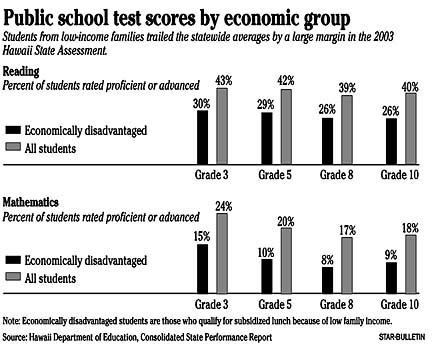

Indeed, the test results show wide disparities by economic status, with low-income students scoring well below their peers. Just 10 percent of low-income fifth-graders, for example, were rated proficient or advanced in math, compared with 20 percent for the state as a whole.

On the reading test, 29 percent of economically disadvantaged fifth-graders ranked proficient or better, compared with 42 percent of the fifth-graders taken as a whole.

The gaps among ethnic groups are also substantial. In math, roughly twice as many Asian students were ranked proficient or better than the statewide percentage. In reading, about 50 percent more Asians got proficient or advanced scores than the statewide ratio. Asians were defined as Japanese, Chinese, Korean and Indo-Chinese.

Caucasians also scored relatively high, with roughly a third more of them earning proficient or advanced scores in math and reading than the state as a whole. That group includes students identifying themselves as Portuguese.

The largest ethnic category, which lumped together Hawaiians, Filipinos, Samoans and "other," scored below the statewide averages. In reading, for example, 34 percent of the Hawaiian/Filipino category was ranked proficient or better in fifth grade, compared with 42 percent of all students. In math, the relative numbers were 13 percent to 20 percent.

The scores of three other ethnic groups -- Hispanic/Latino, Black/African American, and American Indian/Alaska Native -- were also included in the "Consolidated State Performance Report" sent to the federal government last month. But each group represented such a small portion of those tested -- less than 3 percent -- that their results are more variable and considered less reliable, so they are not included here.

The No Child Left Behind Act calls for every student to be proficient in reading and math by 2014.

Although the law requires that states report scores by ethnic breakdown, it holds them accountable for the performance of each school, according to Elaine Takenaka, educational administrative services director for the state DOE. So rather than targeting ethnic groups for assistance, the department is zeroing in on schools that have failed to make academic targets.

"I'm focused more on total school performance, and right now we're working very hard to address how to provide the appropriate kinds of technical assistance to schools," Takenaka said. "If we can provide the kind of support that teachers need and really focus on classroom instruction, I think we can make a difference."

Many schools whose scores fall short are in low-income areas. Nine of the 10 regular public schools along the coast from Nanakuli to Waianae, for example, must now "plan for restructuring" under the federal law because of consistently low test scores. That means they must make changes, possibly even replacing staff or handing school operations to another entity.

The state is sending teams of experts to such schools to help identify problems and address them.

"We are working with the schools, and a select number are being audited," Takenaka said. "We know we have to address the needs of all children, and maybe that's why with No Child Left Behind we're looking at disaggregated groups, so that we truly don't miss any child in the schools."

Kamehameha Schools is also reaching out to public charter schools that have large percentages of Hawaiian students, offering technical help, resources and funds.