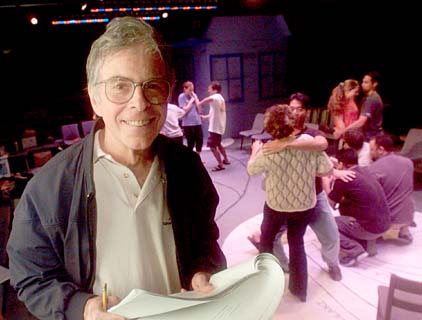

F.L. MORRIS / FLMORRIS@STARBULLETIN.COM

Dennis Carroll, playwright of "Massie/Kahahawai," pauses during rehearsal in the Kumu Kahua Theatre.

A play on the Massie case

will finally see light after being

shelved for more than 30 years

The recent brouhaha over a television movie about the life and times of Nancy and Ronald Reagan didn't surprise University of Hawaii-Manoa drama professor Dennis Carroll. He had a similar experience about 30 years ago when he was about to start casting for what would have been the world premiere production of "Massie/Kahahawai" in 1973.

On stage

"Massie/Kahahawai" presented by Kumu Kahua:Where: Kumu Kahua Theatre, 46 Merchant St.

When: Opens today, with performances running 8 p.m. Thursdays to Saturdays, and 2 p.m. Sundays through Feb. 8

Tickets: $13 today only (with discounts for seniors, students and the unemployed); $16 for all other performances (discounts for seniors, students and groups of 10 or more)

Call: 536-4441

"We were warned not to go ahead because (Thomas) Massie was still alive, and he was opposed to all dramatized accounts," Carroll explained as he recalled the events that caused an innovative play, about Hawaii's most notorious and controversial criminal case of the 20th century, to be shelved for over 30 years.

In 1931, Thalia Massie accused five local men of raping her, an accusation that would spark a racial controversy at the trial of the century and, ultimately, the kidnapping and murder of one of the five young men.

It was Peter Van Slingerland, author of a 1966 book about the Massie case, who warned Carroll that Thomas Massie, Thalia's husband at the time of the incident, might take legal action.

"We consulted some lawyers and were told that students and other people involved with the production could be liable to legal action. ... Whatever representation was made of (Massie and the historical characters) might present them in a bad light, and (the actors) would be open to prosecution of some sort.

"Some people thought (canceling the production) was a cowardly thing to do, but students might have been vulnerable and I didn't feel I could countenance that. ... So, very reluctantly, we put it on the shelf."

Now, with all the principals in the interrelated rape and murder cases long dead, Kumu Kahua is presenting "Massie/ Kahahawai" as a complete staged production for the first time, directed by Harry Wong.

"MASSIE/KAHAHAWAI" is not the usual type of history-based play, in which a playwright imagines what the real individuals might have said or thought. Such works are inherently open to criticism as being the playwright's take, pro or con, on some famous person, event or issue. Unlike "Blood and Orchids," a fictionalized account of the Massie and Kahahawai cases that appeared as a television miniseries in the 1980s, Carroll's script relies entirely on court records, newspaper articles and other published sources.

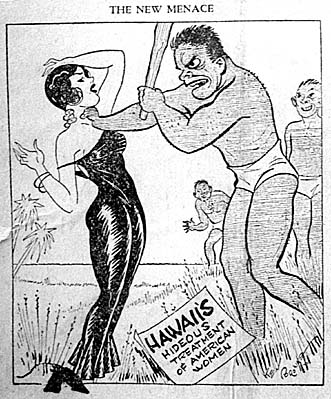

STAR-BULLETIN FILE

On Feb. 1, 1932, this cartoon made the front page of Brevities, a New York publication calling itself "America's First Tabloid Weekly," in response to the Massie story.

"The major sources are the Pinkerton report, trial testimony and some of the secondary books that were then available (in 1973), biographies and so forth," Carroll said. "There's a lot of material on the public record, and I wanted to keep to that."

What the public record shows is a very dark moment in local history:

On the night of Sept. 12, 1931, Thalia Massie, the young wife of naval officer Thomas Massie, left a party at the Ala Wai Inn and walked down what was then known as John Ena Road toward Ala Moana. She was found badly beaten about two hours later and told police that she had been raped by a carload of five or six Hawaiians.

The police were already looking for five "local boys" who had been involved in a minor traffic incident on the other side of Honolulu. One of the "boys" had punched the female passenger in the other car, and she had reported the incident to the police. The driver was the first of the five to be arrested, and he was brought before Massie (who had apparently already overheard police radio broadcasts describing the car; the police brought the other men to her later but never asked her to pick them out of a lineup).

The case against the five was weak. Three of them had criminal records, and two had done prison time for attempted rape, but thorough physical examinations of the men and the clothes they'd been wearing showed no signs that any of them had had sex on the night in question. Nor did an examination of Massie and her clothes substantiate her rape claim. More damning to the prosecution's case was the fact that it was unlikely that the five men could have kidnapped Massie, raped her six times as she said they had, and then been able to get to the other side of Honolulu in time to have had the altercation with the Hawaiian woman.

Amid defense theories that Lt. Massie had beaten Thalia after finding her with another Navy officer, and allegations that police had put Massie's purse in the suspects' car, the jury failed to reach a verdict, and the judge declared a mistrial. The defendants were released on bail.

THE STORY MADE headlines from here to Washington, D.C. The mainland press saw the incident as a threat to whites. One paper said, "Yellow men's lust for white women had unbroken bounds."

One of the young defendants was kidnapped by some Navy men six days after his release and was beaten unconscious.

Less than a month later, on Jan. 8, 1932, another defendant, Joseph Kahahawai, was kidnapped by Lt. Massie, Thalia's mother Grace Fortescue and two sailors. Police detectives later stopped a car being driven by Fortescue. Massie and one of the sailors were with her. Kahahawai's body was in the back of the car.

The grand jury initially declined to indict, but the judge refused to accept their report. So Massie, his mother-in-law and the two sailors -- defended by legendary attorney Clarence Darrow -- were eventually charged with second-degree murder. They were convicted of manslaughter and the jury recommended leniency. The sentence was 10 years, but Gov. Lawrence Judd was facing tremendous political and economic pressure from the Navy and certain members of Congress. The Navy threatened to bring on what amounted to a crippling boycott of local businesses if it deemed the islands unsafe for white women. Various politicians were suggesting that martial law be instituted and Hawaii be ruled by a presidential commission.

Judd commuted the sentences to one hour in sheriff's custody.

Massie, Thalia, Fortescue and the sailors left Hawaii before the four surviving defendants could be brought to trial a second time, and charges against the four men were dropped.

A couple of key questions will probably never be resolved. Who beat Thalia Massie? And who shot Kahahawai?

One of the sailors said years later that he pulled the trigger.

"(The statement) appears in an appendix in Van Slingerland's book, but we weren't allowed to use it ... and we felt it really wasn't all that necessary to use," Carroll said, explaining that he approached the story as "trial as ritual" in a style he described as "a cross between Brecht and Artaud."

He added that the outcome of the Kahahawai murder trial wasn't quite a total miscarriage of justice.

"There's been a lot of material released from archives of various kinds in recent years that indicate that there were attempts made right after the case to try to get (President Hoover) to give (Kahahawai's killers) a pardon ... and the pardon did not happen."

Click for online

calendars and events.