DIANA LEONE / DLEONE@STARBULLETIN.COM

The Hawaiian green sea turtle, or honu, has been recovering steadily during the 25 years it has been protected by the Endangered Species Act.

Comeback

The Hawaiian green sea turtle

rebounds from precariously low

population levels thanks in

large part to a Hawaii researcher

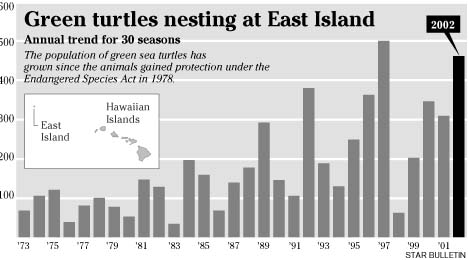

The first year Hawaii's green sea turtle expert counted the animals in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands, he found 67 nesting females at East Island, French Frigate Shoals.

Three decades later, on the same island, George Balazs' research team counted 467 nesting females in a season -- a nearly 600 percent increase.

Using additional data from the main Hawaiian Islands and mathematical modeling, Balazs estimates that Hawaii now has as many as 35,000 mature green sea turtles and perhaps 250,000 juveniles age 6 or under.

What a difference 25 years under the protection of the Endangered Species Act can make.

How to help a turtle

If you spot what appears to be a sick, injured or dead sea turtle stranded on land, call:On Oahu: 983-5730.

On Maui: 984-8110.

On the Hilo Coast: 974-6208.

On the Kona Coast: 881-4200 or 327-4961.

On Kauai: 274-3521.Or, if a turtle has been killed or harmed, you can call the National Marine Fisheries Service at 541-2727 in Honolulu or toll-free at 800-853-1964.

"You ask anybody that's a water person, that lives around the water -- there's a definite increase in turtles," says Robert Morris, the sole veterinarian contracted by the National Marine Fisheries Service to treat sick and injured turtles statewide.

The honu's recovery is significant enough that if the trend continues, the Fisheries Service and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service might ultimately remove the Hawaiian green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) from its threatened-species list.

That step, if taken, would involve public hearings, scientific reviews and time, says Balazs, leader of the Fisheries Service's Marine Turtle Research Project in Hawaii.

And during such deliberations, the turtles would have Balazs going to bat for their welfare -- just as he has for 30 years.

Balazs was a self-described "junior scientist" in 1973 when he first questioned whether people in Hawaii were harvesting honu at a rate faster than the animals could replace themselves.

DIANA LEONE / DLEONE@STARBULLETIN.COM

Jonathan Robinson, above right, a student in the University of Hawaii-Hilo's Marine Option Program, helps researcher George Balazs check the health and growth rate of a green sea turtle at Punaluu Black Sands Beach on the Big Island.

His first few years of data collected in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands -- where honu that later live in the main Hawaiian Islands go to mate and lay their eggs -- confirmed his suspicion.

At the rate people were eating turtle steaks, the risk was growing that not enough of the animals would survive to perpetuate the species.

Balazs' original work helped get the honu listed in 1978 as a threatened species, which means the potential of up to a $25,000 fine and a year in prison for anyone convicted of harming or killing one.

The man universally considered Hawaii's honu expert seems to be the only person surprised at the impact of his work.

"He's a one-man show. He's driven and dedicated to honu. That's his life," says Morris. "His days off, what's George doing? He's out doing turtle work someplace. Not only the Hawaiian turtles, but in Japan and all over the world."

A Canadian couple that has been diving with sea turtles during summers on Maui since 1988 and promotes turtle conservation on their "Turtle Trax" Web site (www.turtles.org) has this to say about Balazs:

"Without George, there would likely be no honu. He's contributed enormously to knowledge of all marine turtles, not just the honu.

"There can only ever be one pioneer researcher -- the first to unlock a door. Jane Goodall was the chimpanzee pioneer researcher," Ursula Keuper-Bennett and Peter Bennett said by e-mail from their winter home near Toronto. "And for honu? That's George."

DIANA LEONE / DLEONE@STARBULLETIN.COM

Tourists at Punaluu Black Sands Beach snap photos of a turtle being returned to the ocean after its examination.

Checkup roundup

It's mid-November, and Balazs is on his way to Punaluu Black Sands Beach Park for his semiannual "checkup" of the honu that live there.As many turtles as possible will be caught, measured for growth and examined for health problems.

Arriving at 10 a.m., Balazs is greeted by professors, staff and 20 students in the University of Hawaii-Hilo's Marine Option Program.

They have a canopy set up on the beach, with a sturdy table in its shade, for Balazs to perform his exam of as many turtles as four-person teams of students can bring to him over the next four hours.

The Punaluu study site has been ongoing for more than 20 years. At 19 other locations around the main Hawaiian Islands, Balazs and his staff of 4 1/2 workers team with a variety of volunteers.

"It's people that make programs like this work," Balazs says.

Within a few minutes, one of the turtle-catching teams is back with the first patient of the day riding in the inner tube, belly up to the sun. After that, every 15 minutes, a crew pops out of the ocean with another turtle.

"They're definitely stronger than you think," says Ashley Herd, a marine science and art student at UH-Hilo. The turtles captured this day measure up to 2 feet wide. "If they want to get away from you, they're gone."

Using a measuring tape and calipers, Balazs measures the dimensions of each animal. The information will be entered into the massive database that has provided Balazs and others raw material for hundreds of scientific papers over the years.

The turtles seem to bear the indignities of the exam with a quiet patience. Their least favorite part appears to be the mouth exam. Several turtles respond by spitting out seaweed.

Balazs wipes up the smelly mess with disposable diapers brought for that purpose and continues.

When the checkup is complete, the turtle gets a blotch of temporary white paint on its shell to keep it from being captured again that day.

The atmosphere on the beach is part science lab, part carnival. Tourists and locals line up behind the plastic caution tapes around the work area to take pictures.

When a field trip of kindergarten and first-grade students arrives, things really get lively. But it all contributes to Balazs' goal of getting more people to know honu. Because as far as he's concerned, to know them is to love them.

"Maybe someday you'll grow up and be a biologist, and you'll use the data we are collecting here today," Balazs tells the students from the Big Island's Pahala Elementary.

For adults, there are handouts with "frequently asked questions" about what the group is doing to the turtles.

While Balazs and a crew work on one turtle, there are always two "on deck" to be examined. The steady supply contrasts sharply with the 1970s to the '90s, Balazs says, when "we'd be tickled pink if we were able to catch even two, three or four turtles" in a day or night of work.

The missing years

After hatching, sea turtles swim away from land. They don't return to near-shore waters until they've grown from palm size to dinner plate size.Balazs' research on turtle growth rates in the wild has shown him that a young turtle lives at sea for about six years.

"What they do during the years they are on the high seas is the last great mystery," Balazs says, and the area he'd recommend to anyone starting turtle research today.

He also found that it takes 20 or more years for a honu to reach sexual maturity in the wild. Though they probably don't live to be 100, they do live a long time. How long may only be known when currently tagged turtles are recaptured.

Advances in technology allow satellite tracking of turtles at sea that was impossible a decade ago. The battery-powered transmitters are attached to a turtle's shell using a surfboard repair kit and last several months.

Between 1996 and 2000, Balazs and Fisheries Service colleague Jeffrey Polovina have tracked 40 Hawaiian honu, more than 20 loggerheads and four olive ridley sea turtles.

A young captive-raised honu made history earlier this year, transmitting its location during a nine-month, 3,000-mile swim around the Hawaiian Islands.

Such information could eventually lead to guidelines for longline fishing boats that would help them avoid ocean areas where juvenile turtles congregate, Balazs says.

Balazs is tracking 27 loggerhead turtles off Japan, three loggerheads off Taiwan, three green turtles off Hawaii and eight loggerheads off California.

At East Island -- the starting point of his turtle research career -- Balazs mounted a "Turtle Cam" last year that scans the 12-acre island from atop a 65-foot pole, providing him with photos and video of turtle behavior dawn to dusk.

Balazs and company also head a network that responds to sea turtle strandings (alive or dead) on all the main islands and study the fibropapilloma tumor disease that has become the turtles' worst enemy now that hunting has been banned.

Despite all his professional time spent focused on turtles, Balazs would be excused for trying try to get away from them during downtime. But honu occupy his leisure time, too. His destination on a recent vacation was a tour of temples honoring turtles on a small fishing island between mainland China and Taiwan. One of his hobbies is photographing, with permission, people's honu tattoos.

One day, he noticed a woman posing a baby on a blanket near a basking sea turtle at Laniakea on Oahu's North Shore, then taking a photograph. The woman told Balazs that she'd been taking monthly portraits of her child with a honu as background.

Balazs was charmed.

"I love to watch how people interact with them."