CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

In fourth-grade teacher Jamie Nip's language-arts class at Honowai Elementary, students Andre Anae, bottom, Aaron Penitusi and Katrinah Luis enjoy class with the other children.

Beating the odds

Test scores rise steadily

at a Waipahu schoolHonowai principal and teachers

share credit for students' success

The numbers look almost too good to be true. At Honowai Elementary School, which serves mostly low-income students in Waipahu, test scores keep going up.

"I was shocked," admits Principal Curtis Young, a genial man with a broad smile, pointing to the charts on his office wall that display his students' progress over the past several years. "We didn't expect to see such dramatic improvement."

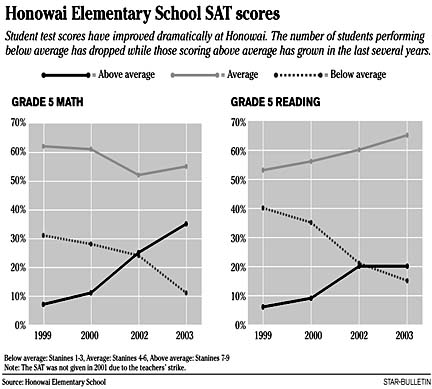

The path is not uniformly even, but the trend is unmistakable. Take third-graders, for example. In 1997, 60 percent scored below average on the reading SAT. This year, just 18 percent did so.

Or consider math. In 1999, the first time that fifth-graders took the SAT, just 7 percent scored above average. This year, 35 percent hit that mark.

At a time when test scores are the focus of a national education debate and schools could face penalties for failing to measure up, Honowai may hold some lessons. This fall, just 39 percent of Hawaii's public schools met federal criteria for adequate academic progress, and Honowai placed among them for the first time.

Studies have shown a close correlation between poverty and low academic achievement. An intense focus on what happens in the classroom is starting to lift students out of that rut at this Leeward school, where 70 percent of students are poor enough to qualify for subsidized lunches.

On the rigorous Hawaii State Assessment, students at Honowai showed a big jump this year over last year, when the test was first given. In reading, 41 percent met or exceeded standards, up from 31 percent last year. In math, it was 20 percent, up from 12 percent in 2002.

The staff at the school, perched on a bluff overlooking Pearl Harbor, credits several factors -- foremost their principal -- for the trend. Asked how to replicate Honowai's results, fifth-grade teacher Leonard Villanueva had a three-word formula: "Clone Mr. Young."

No doubt, Young is remarkable: He was selected as a 2003 National Distinguished Principal by the National Association of Elementary School Principals and the U.S. Department of Education. But the Chinese-Hawaiian educator, who came to Honowai in 1995 after stints as principal at Waianae High and Maili Elementary, points to many strategies at work, with one underlying theme.

"My fundamental belief is if you're going to make a difference with kids, that difference must be made at the level of interaction between the student and the teacher," he said. "Training for teachers, support for teachers, the time for teaching and the resources."

And Young puts his money where his mouth is. The principal draws up the school's budget, but lets his teachers vote on it. They tend to go along with him.

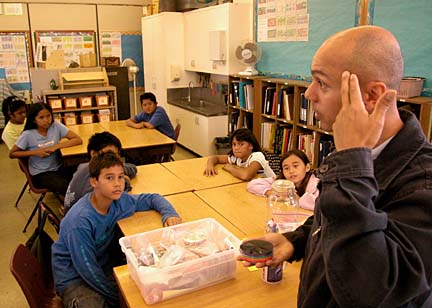

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

Honowai Elementary fifth-grade teacher Leonard Villanueva talks about fractions in his math class. Villanueva won a $25,000 Milken Family Foundation National Educator Award last year for his innovative approach and ability to inspire.

While most public school teachers are lucky to get a few hundred dollars each to spend on their classrooms, Young gives each teacher $2,000 a year. It used to be $3,000, but he had to cut back because funds got short.

"That blew me away," said fifth-grade teacher April Noren, who moved here from Philadelphia and is in her second year at Honowai. "I've never heard of a teacher getting so much for supplies. For my room!"

But that's just part of it. Young funnels money into training for teachers and part-time tutors to give students extra attention. He looks for opportunities to earn free computers, such as through book purchases, rather than spending cash, and applies for grants to supplement the budget.

"The vast majority of the funds are directed toward the classroom, not on trips, not on machines, not on furniture, but on what will make a difference for the kids," Young said.

The collaborative atmosphere, in turn, makes teachers want to give more. About six years ago, the staff decided to tack 15 minutes onto each school day because they thought it would help the students. That adds up to an extra nine days of class time for students every year.

Although the union contract dictates the amount of instructional time per teacher per week, it allows for some flexibility in scheduling. To make up for the longer school day at Honowai, teachers are on a rotating schedule. Every eighth day, they step aside from their classroom duties, and resource teachers, who handle such subjects as art, music and physical education, take their places.

Teachers use the time away from their classrooms to learn new techniques, collaborate with other teachers, or as compensation days away from school. They compare notes on how students are doing, coordinate curriculum to eliminate duplication and learn from each other.

"The collaboration is the key," said language-arts teacher Danice Mineshima, who was at school on a recent "comp day" along with Villanueva, Noren and other fifth-grade teachers, although they could have been at the beach or the mall. Coming to school even on comp days is common at Honowai.

As a high-poverty school, Honowai tapped into federal funds to adopt America's Choice, a school reform model devised by the National Center on Education and the Economy, in 1998. The program sets high standards and clear benchmarks that kids and teachers are expected to meet. It requires regular assessment of students' abilities and offers specific teaching strategies.

When Hawaii's Department of Education introduced its own standards and test a few years later, Honowai was ahead of the ballgame, Young said.

"The younger kids internalized America's Choice standards and are moving up in the school, and that is what has accounted in part for the steady growth in scores," Young said. "The kids were used to taking that kind of test."

Honowai has a diverse, transient student population of mostly Filipinos and part-Hawaiians, along with Samoans, Marshallese and others. As new students enter the school, they must be brought up to speed. The staff puts in long hours to help them along.

"It's a lot of work," said Villanueva, who teaches fifth-grade math. "It's hard work. A successful program like this doesn't come easy."

Villanueva won a $25,000 Milken Family Foundation National Educator Award last year for his innovative, hands-on approach and ability to inspire students. He has misgivings about using the results of a standardized test to rank schools, as required by the federal No Child Left Behind Act, with no reference to where students started.

"High-stakes testing, that's something we can do without," Villanueva said. "But we are always assessing our students, so we know how to plan our lessons. We have to see where the kids are. That kind of assessment is crucial."

The intense focus on test results under the federal law has caused some concern at Honowai.

"There is a super-emphasis on test scores," said Judy Soares, a sixth-grade teacher. "That's all we talk about at staff meetings."

She feels for students who get pulled out of other activities to get extra help on reading and math.

"You see the sense of that, but on the other hand, these are children that need those other subjects," she said. "We're pulling them out of PE or art or music, and making them do reading and math. I can imagine what they're thinking: 'I hate this stuff already, and I have to do it all day?'"

Young said the school is committed to physical education and the arts, and students still get those subjects during their regular school day. Those who are struggling with reading and math may get taken aside for individual tutoring on some resource days.

Villanueva said students don't miss any content areas, but may not get the depth they once did. He used to incorporate a piano and songs into his math lessons, because music reinforces math and reaches some children more readily than numbers. But he doesn't have the luxury of time for that these days.

"That's what you miss," he said. "It would be nice not to worry about test needs."

The staff is focused on getting students ready for testing in the spring. If Honowai meets federal benchmarks a second time, it will be taken off the list of under-performing schools, where it has been for five years. But the goals will be raised the following year, as part of the national requirement to make 100 percent of students proficient in reading and math by 2014.

"There's no light at the end of the tunnel because the benchmarks go up," Villanueva said.

Despite the pressure, Honowai's staff shows remarkable cohesion. Teacher turnover, which tends to hold back student achievement, is not a problem here.

"The only way we lose teachers is when they retire," Mineshima said. "And they're still coming back," she added, waving toward a retired colleague who came back to work part-time.

Teachers say their principal's style and the school's collegial atmosphere make them want to stay.

"You could come in dead tired," Noren said, "but as long as you know that you're being appreciated, you'll do it."