[ MAUKA MAKAI ]

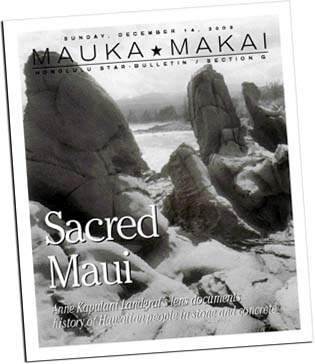

"Hiki'i" is among Anne Kapulani Landgraf's photographs of ancient places that Hawaiians have guarded as endangered, cultural treasures. The photos are compiled into a book, titled "Na Wahi Kapu o Maui."

Photographer Anne Kapulani Landgraf

explores loss of sacred sites,

rights and identity

For Anne Kapulani Landgraf, her camera is a tool to explore and document her culture -- and also to defend it. "I use photography as a weapon," she declares.

The soft-spoken woman with short-cropped black hair possesses a calm, watchful gaze that belies the ferocity of her mission.

Landgraf was 5 when she bought her first camera at a church bazaar for a quarter. Today, she is highly regarded as one of our islands' most exceptional kanaka maoli artists. Her award-winning photographs and mixed-media sculptures honor ancestral connections to ancient landscapes. They also probe the legacy of colonization that destroyed these places and eroded modern Hawaiians' identity as na poe 'aina, the first people of this land.

"Na Wahi Kapu o Maui,"

by Kapulani Landgraf

('Ai Pohaku Press, hardcover,

216 pages, $59.95)

Landgraf's new book, "Na Wahi Kapu o Maui," published this month by 'Ai Pohaku Press and designed by Barbara Pope, opens a rare window to ancient places that Hawaiians have guarded as endangered, cultural treasures.

The book launch coincides with a solo photographic exhibit of silver-emulsion prints featured in the book at Aupuni Artwall at Na Mea Hawai'i and Native Books at Ward Warehouse. The show, which opened last Sunday, runs through Jan. 10.

Inspired to find and visit Hawaii's wahi kapu, or forbidden sacred places, Landgraf has documented prominent geographical, cultural and archaeological features throughout the islands. Her first book, "Na Wahi Pana o Ko'olaupoko," explored the sites of Windward Oahu, where she still lives and works.

"Na Wahi Kapu o Maui" features text written by the photographer and others that relate to these sacred places. Over the course of the seven-year project, supported in part with an OHA grant, Landgraf visited and shot hundreds of sites, arduously trekking into remote areas throughout the islands hauling her large-format, 4-by-5 camera gear.

"I feel really fortunate to have been to these places that no one has been to for so long," she says. "When you have the whole place to yourself, you can see the relationship that our ancestors had with the land, how mountain peaks and underwater ko'a shrines aligned. I was in awe."

The photography in "Na Wahi Kapu o Maui" is accompanied by writings about the sites. "Honokohau," above, captures Ka'anapali's "profoundly deep" valleys. Landgraf, who trekked to sites where no one had been to for generations, says, "When you have the whole place to yourself, you can see the relationship that our ancestors had with the land."

Luckily, Landgraf shares her experience with armchair observers, transporting us with the flip of a page to places that have not been seen by human eyes for generations -- almost all never through the lens: from windswept puu to still-watered marshes pristinely mirroring the sky, to great boulder formations that recall the mystic power of Rapa Nui or Stonehenge.

It is a testament to Landgraf's craft that one can almost feel the heat emanating from the sun-baked pohaku or become vicariously enveloped in a profound silence enlivened only by the trill of a lone passing bird or stray whistling wind -- the kind of experience that those of us living in urban centers, even in Hawaii, rarely get to access these days.

"Keka'a."

LANDGRAF HAS long documented Hawaiian arts and traditional practices for the Native Hawaiian Culture and Arts Program and other Hawaiian arts and educational organizations. Widely exhibited, her work has been recognized with a bevy of prestigious visual art awards in Hawaii and abroad. This fall, Landgraf began teaching Windward Community College's first course in Hawaiian visual arts.

Inspired by the work of cultural historian and treasured icon the late Mary Kawena Puku'i, the '84 Kamehameha Schools graduate majored in anthropology before mastering in fine arts at Vermont College.

Landgraf was initially interested in archaeology but decided not to pursue it after she began documenting the H-3 project. "I saw all that contract archaeology and realized that as long as you record it, you can destroy it," the photographer says. "I think just seeing the site one week and going back the next week and it was gone was horrific."

Landgraf's ethnographic instincts remain, in fact, evident throughout her body of work. During a journalism project at WCC, she conducted oral histories with kupuna in Koolaupoko district, where she lives. Her photographs and interviews were compiled into her first book, "E Na Hulu Kupuna Na Puna'ola Maoli No" ("by the treasured kupuna, the living springs of knowledge"), published by Alu Like Library Project and Kamehameha Schools.

"Pu'u o Pele"

SINCE THE 1970s, Landgraf, along with her former Windward college photography instructor Mark Hamasaki, has also documented community struggles fighting the building of H-3 in Halawa Valley and over Waiahole Ditch water. Her lens offers witness to precious landscapes under siege while honoring surviving traditional practices inextricably bound with nature.

In a recent one-woman exhibit at the Honolulu Academy of Arts, "ku'u ewe, ku'u iwi, ku'u koko" ("my umbilical cord, my bones, my blood"), Landgraf presented edgier material in a venerated venue that has, in times past, exhibited largely non-Hawaiian artists.

She says she wanted the academy's mostly non-Hawaiian audience to confront the legacy of colonization, "to look at the loss of Hawaiian rights." Sorrow and rage seethe from the emulsion of photo collages and mixed-media sculptures juxtaposing historical and original photographs, and layers of personal and traditional symbolism.

In one surreal historical image, a Bishop Museum archaeologist and his wife stand smiling amid thousands of bones excavated from the sand dunes of Mokapu. Both are holding several skulls like prized trophies or spoils of war.

Other works explore the hidden brutality of assimilation that occurs so gradually that it's hardly noticed. As the metaphor goes, if you drop a frog in a pot of hot water, it jumps out immediately, saved by its survival instincts. But, unthinkably, if cold water is heated by slight degrees, the frog is gradually cooked alive.

Other works explore the gradual toll of assimilation. In one photo, the viewer gazes through the keyhole-like opening of a warrior's helmet -- "as if you're looking out," Landgraf explains -- at familiar landmarks like the Moana hotel in Waikiki and Royal Elementary, both built over the sites of destroyed heiau.

Landgraf's emerging works mark her evolution from being a mere observer to an impassioned iconoclast asserting a Hawaiian viewpoint long suppressed. "I was more naive when I first started, to now where, as I get older, I want to go all out and risk being more political, more in your face, not so subtle like the landscapes," she says.

Landgraf hopes her work "helps breaks walls and reveal injustices," she says. "I like the idea of challenging people and making them think."

Click for online

calendars and events.