‘Red Trousers’ gives

a rare peek inside

the risky world of

Hong Kong stuntmen

The Hong Kong stuntman stands atop a freeway overpass about 35 feet above where a truck will rumble under. The stunt calls for him to land on the speeding truck, roll into a standing position, then leap onto the top of a minivan moving in the opposite direction before jumping to the ground to complete his make-believe getaway.

Since the Hong Kong authorities wouldn't grant a permit for such a public disruption, the stunt must be done at dawn and the performer only has 20 minutes to prepare. He receives $25 and expects to suffer some injuries but believes, like his counterparts, such risks are necessary if he's to rise to the next career level as either a stunt coordinator or director.

'Red Trousers:

Screens: 8:45 p.m. Tuesday at the Hawaii Theatre and 8:30 p.m. Friday at the Palace Theatre in Hilo

The Life of the

Hong Kong Stuntmen'

This is the inside look provided by the documentary "Red Trousers: The Life of the Hong Kong Stuntmen," about the men and women who endure risks and harsh conditions to make it in the competitive business of stunt work.

The 90-minute film -- written, produced and directed by Robin Shou -- is a featured documentary at this year's Hawaii International Film Festival.

"Red Trousers" is interspliced with a short film titled "Lost Time" which demonstrates how stunts are set up and shot.

Shou, who co-starred in "Mortal Kombat" and is a veteran of more than 20 Hong Kong action films, provides, in his directoral debut, an inside look into the art of dangerous action.

"RED TROUSERS" is a term that originated at the Beijing Opera school, where Chinese children were apprenticed as young as 6 to learn martial arts and acrobatic skills. Red trousers -- in addition to being the color of pants worn during training -- symbolized the indentured servitude of children bound by contract to live and train at these schools.

Chinese opera tells stories through a synthesis of stylized acting, singing, mime, acrobatic fighting and dancing, and the "red trousers" were the workhorses of the company.

"The hard training at these schools meant physical success as a performer for many of these children who would, like Jackie Chan, become world famous as stuntmen, stunt doubles and actors," Shou said.

The phenomenon of the traditional "red trousers" training is disappearing, and the Hong Kong schools have nearly all closed, Shou said.

"It takes so much time to get to that level and sacrifice," he said. "It's less dangerous and you can make more money working at McDonald's."

Early red-trousers stuntmen were also influenced by the martial arts films of Hong Kong's Shaw Brothers studios.

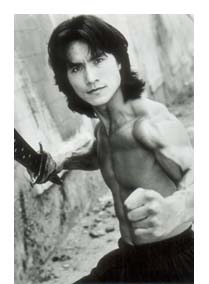

NEW LINE CINEMA

"Red Trousers" director Robin Shou starred as Liu Kang in "Mortal Kombat."

"You could learn a lot from that period of filmmaking -- how to be a stuntman, how to be a stunt coordinator -- from those great filmmakers," he said.

As the popularity of the traditional Chinese opera started to wane in the 1950s, teachers steered students toward movies so they could keep working.

"Red Trousers" is Shou's tribute to this "dying breed" of performers who spent hours each day exercising, including hours of handstands.

"They established the platform, the foundation, with their discipline for the rest of us," Shou said. "They gave everything they had and received very little, but that was their tradition."

SHOU, who has a civil engineering degree from California, was born in Hong Kong but came to the United States at 11. The 6-foot, 165-pound Shou is a four-time winner of the Traditional Forms, Grand Championship and the National Forms Championship in the Wu Shu style.

He made his Hollywood debut playing Liu Kang in the 1997 movie "Mortal Kombat." Shou went to Hong Kong as a tourist where a film producer offered him a small role as a KGB killer. Shou also co-starred with the late comedian Chris Farley in "Beverly Hills Ninja" that same year.

Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan are the names that come to mind when thinking about Hong Kong martial arts films. In a published story, Chan said he had to sign, as a child, a 10-year contract to learn at the Beijing Opera school.

"I think many now know what that training was like for me," Chan said. "Up early, handstands on chairs for hours, 5,000 punches and kicks. I would never train like that again."

The documentary took Shou more than two years to complete, and his interviews with stunt people are unrehearsed.

"People just want to think these people are some kind of kamikaze, but that is very untrue," he said. "They are professionals who take great pride in their work."

There is no union per se for the stunt people, no medical coverage other than workers' compensation.

The film features a stuntman who was required to ride a motorcycle off a 50-foot cliff. When his safety harness failed, the driver slammed into the rocks below, shattering his pelvis and nearly losing an eye.

"He got his $25 a day for two days work and $1,500 in compensation from the production but was unable to work for two years," Shou says. "He wouldn't go home injured like that because he was embarrassed, but he's back at work and says, 'This is who I am.'"

An American production would have more sophisticated safety equipment, but the devices are limited or nonexistent in Hong Kong, Shou says.

"If we have a 30-foot fall, we might have to do it on a stack of cardboard boxes because another production may be using the only airbag," he said. "If you call yourself a stuntman, you just don't complain, because this is what you do."

Click for online

calendars and events.