[ MAUKA MAKAI ]

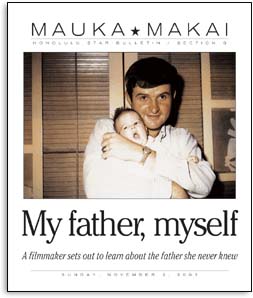

COURTESY OF KAT TRAGOS

Tracy Tragos, holding a portrait of her father, Donald Droz, grew up amid silence about him.

In search

of DadThirty-plus years after

her father's death in Vietnam,

Tracy Tragos finally breaks

her family’s silence

WHEN you look in the mirror, what do you see? Eyes. Nose. Mouth. Hair. Chin. But the eyes -- they're not just "eyes." They're your eyes, and they come with a history: "Blue, like my sister's and everyone else on my father's side." Or, hair: "I have thin, brown straight hair like cousin Kathy, even though the rest of the family has thick, black hair." Chin: "I got this scar when my brother pushed me off my bicycle in the third grade." The way we see ourselves, the way we define ourselves, is based on our history, on who and where we come from and what we've done.

Until a couple of years ago, filmmaker Tracy Tragos felt she had only half that sense of identity. Tragos' father, Navy Lt. Donald Droz, was killed in the Vietnam War in 1969 when she was 4 months old. Her mother, overwhelmed by grief, coped with the loss by packing away all traces of Droz and replacing his presence with silence. Droz's family, wanting Tragos to have "as good and normal a childhood as possible," put on happy faces. But they, too, kept up the silence.

"Be Good, Smile Pretty"

Part of the Hawaii International Film FestivalGolden Maile award nominee for best documentary

Screens: 3 p.m. today and Wednesday at Signature Dole Cannery

Admission: $8 adults; $7 children, military, students and seniors 62 and over; free to individual festival Ohana members ($6 each additional ticket) -- tickets for the film available today and Wednesday at the multiplex's box office

Call: 528-HIFF (4433)

"Talk of my father was tangled up with the war and grief," she said. "I never asked about him, never said I needed to know. So I am also responsible for that silence, despite a deep longing to know about him. I didn't want to cause more grief."

But in 2001, Tragos was surfing the Internet and keyed her father's name in a search engine. Up popped an account of Droz's death by one of the men who was there when he was killed. That was the catalyst for Tragos to begin asking questions about her father, and in 10 days she had borrowed a video camera and had begun interviewing people about who her father was.

The result is "Be Good, Smile Pretty," a moving documentary about Tragos' quest to find out about the man who was her father. The film has been racking up awards, having won the Documentary Feature Jury Prize at the Los Angeles Film Festival, the President's Award for Excellence in Documentary Film from the Vietnam Veterans of America, and the Audience Award for Best Documentary Feature at the Aspen Filmfest. It will be shown for the first time in Hawaii today at Signature Dole Cannery. Tragos will be in Honolulu for the festival.

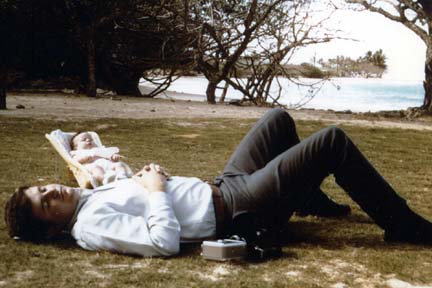

COURTESY OF JUDY DROZ KEYES

Tracy Tragos met her father once, when she was 4 months old, while he was on R&R in Hawaii. He was killed two weeks later.

WHEN TRAGOS took her place behind the camera, she'd only meant to document discussions she was having with her mother. Tragos' mother had begun grief therapy for Droz's death more than 30 years after he was killed, and she was "talking about him in a way she never had before."

Trunks with Droz's belongings and suitcases filled with his letters came out of the garage and the closets. "I never even knew (these things) existed, and the stories! My mother and I were in such a state, I thought, 'Some of what she's saying will get lost, and she'll stop talking again.' So I began filming our conversations," Tragos said.

Eventually, she saw a different potential for her documenting.

"I couldn't describe in words the depth of how this event had shattered our existence. I wanted to tell my story."

To do that, Tragos needed the remembrances of people who knew her father. As it turned out, the "telling" became therapeutic for everyone who had held their silence for so long.

"One part I didn't include in the film was of my mother looking at all her diplomas framed on the wall. She said she felt her whole life was a sham," Tragos said. "Today, she no longer feels like she's living a sham."

The Droz family, Tragos' grandmother, uncle and aunt, whom she also approached with her camera, went through similar changes.

"Initially it was very difficult for them," she said. "But I was so overcome with the need to do this that they said, 'I will do this for you.' They were very courageous and they trusted me.

"Now, it's so wonderful. My uncle probably saw the film more than 40 times. I think it's something that allows him to learn about his brother and gives him permission to get answers to the questions he never thought he could ask."

Droz also interviewed her father's war buddies, who found great relief and solace in being able to speak about Vietnam. "For some of these veterans, no one wanted to hear about their experiences, and they had a need to talk about it," she said.

TRAGOS' STORY caught the interest of "60 Minutes" when a producer read a newspaper article about her documentary. That led to the show's crew following Tragos and her mother back to Vietnam, where they traveled to the site where Droz was killed. (The piece aired last week on CBS.)

"One thing that surprised me is how important it is in Vietnamese culture to live with the memory of one's ancestors," she said. "There was such an understanding of what I was doing from the get-go. People (in America) thought it was too traumatic, but the Vietnamese understood immediately."

Droz died along the Mekong Delta. Tragos said the place was "so unlike what she had imagined it to be."

"It was not picturesque, even though the country itself is beautiful. It smelled bad, and the mud went up to my knees. My first feeling was that this was an awful place for my father to die.

"But then, up on the bank where it was dry, stood a small, very fragile 3-foot shrine. A woman in the hamlet there erected it in 1975 for the men who died too young there. Thirty men died. It was an amazing thing to find, to know the memory of all who were killed had been honored.

"When I left for Vietnam, I had felt the trip was a one-time thing. But now, I have a sense that this is an important place to visit," Tragos said.

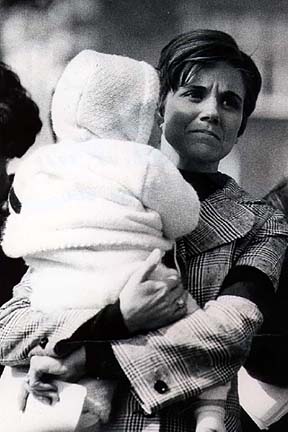

COURTESY OF JUDY DROZ KEYES

Navy Lt. Don Droz and his men were traveling the Mekong Delta when they were attacked by Viet Cong and Droz was killed.

TWO YEARS after Tragos began filming her mother's tearful memories of the man they both lost so long ago, she said, "To know where you come from, to know what makes up half of you -- it's such an empowering, strengthening thing."

The film documents important moments along the journey of this discovery. There's Tragos and her mother listening to a tape recording of her father talking. It was the first time Tragos had ever heard his voice. Then there's the Navy buddy who talks about how Droz convinced him to take Droz's place on a dangerous mission so Droz could stay alive to see his then-unborn daughter. There's home footage of that one and only father-daughter meeting, taken two weeks before Droz was killed.

"It was so important to hear his voice, to have a sense of him. To know he existed. To know he wanted to be my father," Tragos said. "Hearing how he negotiated to live to see me -- I can think about that now and draw on the strength of that love.

"It's important to me, as a woman in my 30s who's thinking about starting a family, to have a sense of my own history. I'm tremendously grateful to know where I came from."

So what does it mean to be Don Droz's daughter?

"It's still something that I have to reconstruct, but for the first time, I have a reconstruction," Tragos said. "I can ask myself, What would my father do? What would he say in this situation? Because I have a sense of who he was.

"I like myself better as his daughter. The things I used to see as flaws -- like the way I sunburn easily -- I appreciate now because I see them as part of my father.

"He was what I always hoped for. I always imagined someone funny who would elbow me in a movie or when something was funny, because I lived in a serious house where there wasn't a lot of laughter. Now, it's great to have permission to laugh. Because of my mother's grief, I never gave myself permission to be that way," she said.

COURTESY OF JUDY DROZ KEYES

Judy Droz, Don Droz's widow, holds 6-month-old Tracy at an anti-war protest in October 1969, six months after her husband's death.

TRAGOS' SUCCESS in finding out about her father has motivated her to try to help other children of men killed in the Vietnam War through outreach work. She also hopes her film will serve as inspiration for other families.

"In 2002, I visited the Wall (the Vietnam veterans' memorial in Washington, D.C.), and for the first time, I talked with other people who lost fathers in the war," she said. "There are other children who still don't have permission to talk about their fathers. Grief is difficult, and people can wall it off because they can't deal with it. Particularly with the Vietnam War, there is more reason for silence. There is a stigma, and such strong judgment, that there's a lot of hurt.

"So I'm hoping my film encourages other journeys."

Click for online

calendars and events.