ANSEL ADAMS / LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

Japanese-American internees watch and play baseball in 1943 at the Manzanar War Relocation Center, located in eastern California, north of Lone Pine.

Internees want

baseball site restoredJapanese Americans from

the Manzanar camp say the

diamond was a key part of life

LOS ANGELES >> Locked away from the world by the U.S. government, the prisoners of the Manzanar internment camp passed the hours with the most American of games.

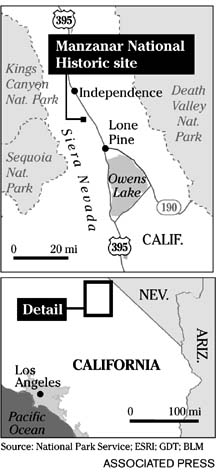

The 10,000 Japanese Americans taken to the Owens Valley camp had no privacy and lived in cramped barracks in a single square mile fenced in by barbed wire.

The firebreaks between buildings provided enough room for baseball diamonds.

"That was the major sport," said Jack Kunitomi, 88, a member of an older team called the Has Beens during his first summer of internment. "Before the evacuation, there were leagues all over California. It was very important for the young people. What else could they do, besides work?"

The National Park Service is restoring the main auditorium built by the internees, to be unveiled in April 2004 as an interpretive center with exhibits and theaters. But a rebuilt baseball diamond won't be part of the celebration -- a decision that some former internees say overlooks one of the mainstays of life in the camp.

Kunitomi's team played softball for lack of baseball equipment. He was allowed to leave in the winter, first to pick sugar beets in Idaho, then to serve as a U.S. Army translator. Over the next three years, players ordered equipment and formed more than 80 baseball teams that played each other and even teams from high schools near the camp.

Kunitomi, now a retired teacher living in Monterey Park, said a restored diamond would help children visiting Manzanar understand the boredom of life in the camp, as well as internee determination to keep active.

It would also underscore how much they continued to embrace the United States and its traditions, even as the country locked them away for fear they would aid Japan in World War II.

"It was very important to the young people because they needed something to boost their morale," said Kunitomi's sister, Sue Kunitomi Embrey, 80, of Los Angeles. "There was nothing else. There were no telephones or cars. There were no movies you could go to, except later. They had weekly movies. Whenever they had a game, we went."

Embrey now leads the Manzanar Committee, a group that pushed for preserving the camp, and organizes an annual trip to the site.

Tucked between the Sierra Nevada and Death Valley, Manzanar was one of 10 camps nationwide where 120,000 Japanese Americans were detained during the war because they were considered security risks.

The most vocal advocate of restoring the main diamond at the camp was never an internee, and isn't Japanese American. Author and playwright Steve Kluger, who has written about baseball in novels including "Last Days of Summer," said he had been a gay rights activist for years when he began pushing for the diamond.

"If you're a discriminated-against minority you've got to fight for each other," he said. "You've got to be able to lend your efforts to whoever, whether it's your group or not."

Kluger hopes that someday Japanese-American teams will again play local high schools at Manzanar, and has helped raise $23,000 to rebuild the diamond.

But Manzanar site superintendent Frank Hays said the Park Service can't take money from everyone who wants a historic monument changed. He agrees that baseball was an essential part of life at the camp, but said a memorial is no place for games. Remnants of the original diamond remain, he said, including the pieces of clay used to hold the bases in place, and shouldn't be disturbed.

"When you can actually see the real history, that's what's so attractive about historic sites," Hays said. "You go to see pieces of the real thing, the real remnants, the real history, rather than some re-creation."

He has asked Kluger to work with the Park Service's process for deciding what to restore, which includes years of public comment and evaluating what projects to focus on first.

The agency's priorities now include reconstructing one of the camp's eight guard towers and restoring a mess hall. Hays said officials also hope to eventually restore part of one of the 36 blocks of barracks, and preserve apple, pear and peach orchards near the site.

The park has a staff of nine, but no federal money has been allocated for new restorations. Manzanar recently formed a group to seek money from private donors.

Both sides agree the other means well and are devoted to the site, but that hasn't prevented each from pushing hard for their version of the diamond.

Kluger went this week to Washington, D.C., where he said he found two members of the House of Representatives willing to override the Park Service and build the diamond. He said it's too early to name them.

"Right now it's the shell of the park," Kluger said. "It has conscience, it has good intentions. What it doesn't have is heart. ... Heart is something you put in when you don't have to. Going the extra mile for something you don't have to do."