Graduates

grapple

with loansThe U.S. government says

the default rate for isle students

ranks 22nd in the nation

It's hard to refuse money, even the kind that needs to be paid back. And so Rowena Castanaga, a senior at the University of Hawaii, never has.

With every semester's financial aid award letter, the elementary education major accepted up to $3,000 in student loans -- a fact she's now regretting in her sixth year at the institution.

"I'm happy to finish soon. I grad this semester," she said yesterday as she studied for a test with friends at UH-Manoa Hamilton Library.

Once graduated, the temptation for Castanaga to take out more loans is gone, she said. But it also means facing for the first time the debt she's accumulated over the course of her bachelor's degree.

Nearly 6,000 college graduates in Hawaii, who join the work force after anywhere from two (associate's degree) to eight (doctorate) or more years in school, begin to tackle their student loans each year.

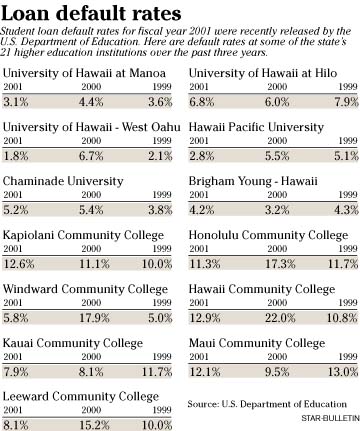

And in 2001, about 6 percent, or more than 300 borrowers, defaulted on their loans, according to recently released statistics. That's slightly higher than the national average, but low interest rates and pressure on financial aid offices to educate students on loan repayment dropped the rate almost 2 percentage points from the year before.

Hawaii's default rate is the 22nd highest in the nation, according to new U.S. Department of Education statistics. Wisconsin recorded the nation's lowest default rate, at 3 percent, while Alaska had the highest, at 9.2 percent.

"It takes a lot of work" to remind students of their loans once they graduate, said Sheryl Lundberg-Sprague, financial aid director at Hawaii Community College. "It's a battle I fight on a daily basis."

The Big Island institution, which has one of the highest default rates in the state at 12.9 percent, has students who default on as little as $3,000.

Those in danger of sliding into default can apply for deferments or other programs that spread out payments into more manageable chunks, Lundberg-Sprague said.

On average, Hawaii's community colleges recorded higher default rates than the state's four-year institutions -- a statistic that Lundberg-Sprague attributes to lower salaries for those with associate's degrees than those with bachelor's degrees.

"It's very difficult, even after they've received their (two-year) degrees, to find employment with sufficient income," she said. "Students should definitely only borrow what they absolutely need."

But many students don't heed her advice, accepting loans for nonessentials or using them in place of a part-time job, she said.

That's because "they think it's free money," said Jared Dolan, a senior at Hawaii Pacific University. They forget that "it's going to become non-free money."

Dolan, who receives about $5,000 in loans a semester, said even he didn't realize the enormity of his debt until he met with a loan officer at his institution. He said he'll apply for more loans when he enters law school next year.

Undergraduates listed as dependents can take out a maximum of $23,000 in federally subsidized loans over the course of their degree. Independent students can take out $46,000, half of which is subsidized, Lundberg-Sprague said.

Graduate students are able to borrow $8,500 a year in subsidized loans and $10,000 annually in unsubsidized loans.

Walter Fleming, associate vice president for student support services at HPU, said Hawaii students don't borrow as much as students in other parts of the nation, so they are better able to repay their loans.

Tuition at most of Hawaii's higher education institutions is lower than elsewhere in the nation, he said.

About 3 percent of students who graduated from HPU in 2001 went into default, compared with about 5.5 percent the year before. UH-Manoa had a 2001 default rate of 3.1 percent and a rate of 4.4 percent the year before.