Bus drivers’ pay

sets tone for public

employee talksUnions feel pressure to

negotiate raises after gains

by police and the Teamsters

The revelation that Oahu bus drivers have higher base salaries than police officers, firefighters, teachers and University of Hawaii instructors has increased the pressure on union leaders representing those and other workers.

"We just feel we're underpaid and overworked," said Kelly Yamamoto Fuentes, a paramedic for the city and county for the last 17 years and a member of unit 10 of the United Public Workers union. "We're not saying that the bus drivers are overpaid. We're saying that we are underpaid."

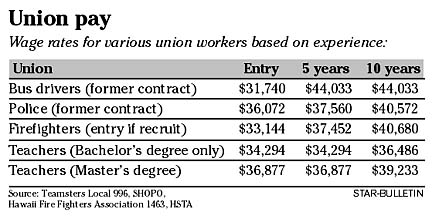

During the 32-day bus strike that ended last week, Oahu Transit Services Inc., the private company that manages TheBus for the city, circulated the numbers that after five years bus drivers, represented by the Teamsters union, make $44,033. At that point their salaries top out, with little ability to make more.

Counting only wages and no pay differentials or overtime, a police officer with five years experience makes $37,500, a firefighter earns $37,400, and a public school teacher $34,294 (with a bachelor's degree) or $36,877 (with a master's degree). UH instructors make between $38,259 and $42,567, depending on factors such as degrees and whether they work at a community college or on the Manoa campus.

"The unintended consequence of publishing the $44,000 figure is it convinced everyone who already felt underpaid that they are underpaid. And I think that will make wage increases a very important issue this next round," said Lawrence Boyd, an economist with the UH's Center for Labor Education and Research.

Boyd said, "The $44,000 has put union leaders in the position of having to push for higher wages."

The comparison, based only on wages, is somewhat misleading because benefits, which vary greatly from union to union, aren't factored in, nor are promotions that are possible in some professions and not in others, steps in pay based on experience, or other pay differentials. Some union leaders dismiss the figures as an apples-to-oranges comparison.

Nonetheless, that $44,000 is out there.

And it is cranking up the heat on union leaders, who are heading into contract negotiations, to get wage increases for members who have endured wage freezes while the state has languished in a decade-long economic slump.

"I love my job, but we've lost 80 paramedics over the last few years out of about 200," said Fuentes. "They're saying being a paramedic doesn't pay enough and are going to more lucrative professions like emergency room nursing. But I think we provide a crucial service."

Bill Puette, a labor history professor at UH, said he understands Fuentes' frustrations.

"There is a sense among public workers that there has been wage erosion and belt tightening and now it looks as though the economy is more stable, and barring any unforeseen disasters, the economy is back on track and should support wage increases," said Puette.

At the same time that public employees are grumbling more about being underpaid, they also are looking for signs that the state can foot the bill.

One such sign came last week when an arbitrator awarded members of the State of Hawaii Organization of Police Officers a 16 percent pay increase over four years.

"There's a positive message in the SHOPO contract that in the eye of the arbitrator, the state is not in a poverty situation, so the employer can afford the pay increase," Boyd said.

And in April an arbitrator awarded Hawaii Fire Fighters Association Local 1463 a 3 percent raise over the life of its two-year contract.

"The state fought us pretty hard throughout the arbitration," said Capt. Robert Lee, HFFA president. "They, of course, kept saying how we deserved more (pay) but that they were bound by the (poor) economic conditions of the state."

Unlike the firefighters, the police have had trouble keeping trained officers from moving to the mainland for higher salaries.

"Police have had a very severe retention problem," Boyd said. "They have been losing well-trained officers to other jurisdictions because of pay, so it's understandable that retention had to be addressed with higher wages."

Meanwhile, the Hawaii State Teachers Association has had retention problems of its own due to low pay, according to Deputy Executive Director Joan Husted.

SHOPO's increase is expected to fuel the teachers' negotiations for higher pay. Negotiations are at an impasse and the teachers are tentatively expected to go back to the table on Jan. 9, said Husted.

HSTA President Roger Takabayashi said, "We're all public servants and we are all underpaid. Teachers are really grossly underpaid here."

While the police got 4 percent a year raises for four years, the bus drivers accepted a wage freeze for the first three years of the five-year contract and increases in the last two years. But three years into the new contracts, the police officer with five years experience would earn $43,939, still slightly less than the highest-paid bus driver.

Nonetheless, public unions hope the SHOPO deal is a sign that their members may win pay concessions or, at least, not lose financial ground when the cost of benefits such as health care premiums are increasing.

"I think we will see a wage increase and a continuation of our step movement," said Randy Perreira, deputy director of the Hawaii Government Employees Association, the state's largest union with about 24,000 members in six bargaining units.

Perreira said he hopes the SHOPO and firefighters contracts "will work in our favor."

But Ted Hong, the state's chief negotiator, said the Lingle administration has repeatedly said that in the post-9/11 world, first responders such as police and firefighters are in class of their own.

"First responders should get a larger increase to reflect their increased responsibilities," said Hong. "Couple that with limited resources and law enforcement really has to take a top priority. And we have said that to every public sector leader since last January and we still maintain that position."

Perreira said HGEA's six units will meet this month to negotiate a contract that has been extended until June 2004.

"We haven't had much opportunity to meet face-to-face with the employers so we're happy about the meetings this month. We would rather a voluntary settlement than an arbitrated one," said Perreira.

Last session, the union won the right from the Legislature to arbitrate. The Legislature can approve or veto an arbitrated contract and the governor has the power to veto it or appropriate money for it.

"HGEA has been very understanding about the state's financial conditions and has been very cooperative," Hong said. "They extended their contract."

Hong acknowledged that projections are better for state revenues and that HGEA will be seeking wage increases. He said if they can't reach an agreement, he expects binding arbitration to begin in January so they can resolve the contract before the legislative session ends in May.

Senate Majority Leader Colleen Hanabusa (D, Nanakuli-Makua) said that with recent increases in state revenue projections, she expects the public unions will ask for wage increases and will win some.

Hanabusa noted that arbitrated contracts, which are decided by a third party looking at the state budget, tend to grant higher pay increases.

"The arbitrated contracts set the tone for everyone," said Hanabusa. "The police got 4 percent (each year) and I'm not sure everyone will get that, but we will see some increases.

"The teachers and the professors have both made it very clear they want wage increases," Hanabusa said.

The University of Hawaii Professional Assembly has been waiting since May to sit down with the state's chief negotiator.

"Salary increases are the only remaining issue," said J.N. Musto, the executive director of the faculty union, which represents 3,400 members in the statewide university and community college system.

Musto said that UH faculty are paid far below faculty at peer schools on the mainland. Unlike other public unions, he said UHPA's members contribute to state revenues by teaching students and attracting tuition.

"The question is not the state's ability to pay, it's the state's willingness to pay," said Musto. "They are not willing to afford a salary increase if they have to raise taxes or cut other expenditures."