Look at Nuuanu's lush forests to see what all of Hawaii must have been like to the first people who settled here, bringing change that continues to this day. All neighborhoods have a life cycle that begins with birth, aging, decay and sometimes gentrification or industrialization.

Iwilei, which once comprised fishponds, was deemed to have greater purpose as a center for trade, due to its deep harbors. It's no coincidence that Benjamin Dillingham chose to build Oahu Railway & Land's eastern depot at the edge of Iwilei. In a darker take on business transactions, it was also home to brothels frequented by sailors. These days, the industrial area is giving way to a shopper and moviegoer paradise with activity centered around the refurbished Dole Pineapple Cannery.

A younger generation probably cannot imagine Halawa without Aloha Stadium, once a place of housing for low- and moderate-income families. The stadium also displaced an open-air theater, piggery, saimin stand, cane field, watercress patch and stream. Yet, we cannot imagine what life would be like without UH football games, swap meets and concerts at the stadium.

Where one lifestyle is lost, another emerges.

Iwilei | Halawa Housing

BACK TO TOP |

RICHARD WALKER / RWALKER@STARBULLETIN.COM

The Oahu Railway & Land Building at the corner of Iwilei and King streets is an area landmark.

It began with a jail,

railroad and brothelsBut they gave way to the Dole cannery,

which was replaced by shops and theaters

From the beginning, Iwilei has been a kind of marginalized industrial zone, a place where people worked but didn't choose to live.

The region is flat because it consists of filled-in fishponds. When Kamehameha shifted the capital of the islands from Waikiki to Honolulu, he did so because the harbor was deep enough to serve deep-draft European sailing ships. The first wharf was built atop the remains of a sunken vessel at the foot of Nuuanu Street in 1837, and Honolulu began to rapidly organize, including the building and naming of streets. What we now know as Iwilei Road ran between the Kawa and Kuwili fishponds.

It was originally called Prison Road, as a large coral-rock jail was built on the cusp of land jutting between the fishponds. Called "The Reef" because of its coral, the jail had a commanding view from the roof, which became a favorite place to take photographs.

In 1889, Benjamin Dillingham's Oahu Railway & Land opened the eastern depot of its Honolulu-to-Aiea line -- near where the 1927 OR&L building stands today -- along a right of way that stood only two feet above high-tide lines. Businesses in the area quickly began dumping earth and coral rock into the fishponds, and a kind of Wild West boomtown of cheap buildings sprang up in the area.

The business was sex. Other than the prison and railroad, Iwilei was known at the turn of the century for its rows of shoddily constructed brothels.

Writer W. Somerset Maugham vividly described muddy streets full of brightly painted houses and blaring gramophones, where Japanese and American prostitutes would stand in windows and flash their breasts.

Although the territorial government required that prostitutes be registered, medically monitored by inspectors and keep their activities limited to Iwilei, by 1916 the red-light district was officially shut down.

One colorful, evicted prostitute shared a ship ride to Pago Pago with Maugham, and he was so taken with her that he made "Sadie Thompson" the central character in his short story "Rain," eventually made into three films and a Broadway show.

By the 1920s, Iwilei became known for its many businesses, both small and large. The crowning industry there for nearly 75 years was the Dole Pineapple plant, crowned with its famous pineapple water tower.

Today the cannery buildings have been gentrified into tourist and shopping-oriented venues.

BACK TO TOP |

STAR-BULLETIN FILE PHOTOS

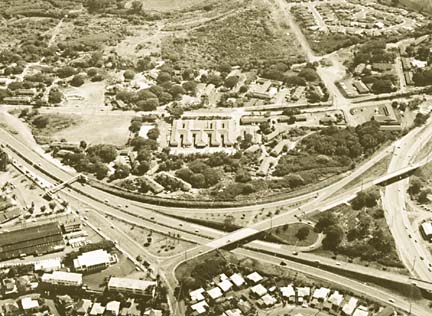

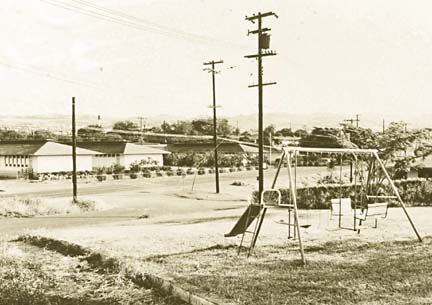

Halawa Housing (center, shown in 1969) was demolished to make way for construction of Aloha Stadium and an interchange connecting the H-1, H-3 and Moanalua freeways.

Stadium replaced

low-income homesA freeway interchange also stands where

the converted military barracks used to be

Patty Burgo remembers exploring the tunnels that stretched from the Navy's Pacific Command Headquarters at Pearl Harbor to Halawa Housing where she lived while growing up in the late '50s and early '60s.

"We used to go in them with flashlights as kids. I think they called them bomb shelters," Burgo said.

The Halawa Housing of Burgo's childhood years is gone now, displaced by Aloha Stadium and the interchange connecting the H-1, H-3 and Moanalua freeways.

Halawa Housing was a collection of former World War II barracks that were converted into family units.

There were four to six families per building, and the units had three or four bedrooms, Burgo said.

"Girls in one room, boys in one room and parents in one room," she said. Burgo lived on Shaw Street.

The interior walls of the units were made of canic, a pressboard of sugar cane fibers.

"Outside was wood but inside was canic. The only thing that was wood inside was the doors," said Selene Souza, who grew up on Nevada Avenue.

Souza believes the canic was responsible for aggravating her asthma.

STAR-BULLETIN FILE PHOTOS

Halawa Housing was demolished to make way for construction of Aloha Stadium and an interchange connecting the H-1, H-3 and Moanalua freeways.

She said she was sick every weekend until her family moved out of the housing when she was in fourth grade.

The Navy built the barracks just prior to World War II. After the war, the Navy retained ownership of the land and buildings but allowed the state's Hawaii Housing Authority to use the buildings for temporary or transitional housing for low- and moderate-income families.

There were about 1,000 families living in Halawa Housing when the city's Honolulu Redevelopment Agency announced plans to build a stadium in Halawa.

However, by the time the wooden structures were to be demolished, less than half of the families qualified for low-income or state housing.

In 1968 the city and state broke ground on two housing projects for the low- and moderate-income families who were going to be displaced. Makalapa Manor and Puuwai Momi were built on 26 acres a few blocks away from Halawa Housing.

Burgo said the stadium also displaced an open-air theater, piggery, saimin stand, cane field, watercress patch and a stream in which she swam.

"I feel sorry for the kids today because they will never know what it's like to hike all over the place from Red Hill to Moanalua Gardens and pick opae from the streams in Halawa Heights," she said.