When sugar was king, Kahuku, Waialua and Waipahu bustled with jobs and the commerce to support the daily needs of those who worked the fields. Dethroned by tourism, sugar left its inhabitants to search for new trades, but these neighborhoods have not yet surrendered their identities as plantation towns.

Far from Oahu's urban core, Waialua and Kahuku hold to the pith of agrarian life as farmers plant tomatoes, herbs and corn where cane used to grow. Waipahu, caught in the growing corridor of freeways and commercial development, struggles to redefine itself as its aging boundaries melt in the glare of bright new neighborhoods.

Kahuku | Waipahu | Waialua

BACK TO TOP |

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Masa Fukuyama, left, Thomas Nakayama, Isamu Tatsuguchi and Ted Kunimitsu sit in front of the Kahuku Hongwanji Mission temple. These men, whose ages range from the early 70s to the 90s, are affectionately known in the community as local old-timers and have borne witness to decades of transition in Kahuku.

Being in Kahuku

is like being on

another islandOld-timers remember when the roads

were made of coral and plantation life ruled

When you're getting close to Kahuku, you know it.

There are signs, of course, proclaiming the goodness of sweet corn, or of football championships, or garlic shrimp. But there is something else, too. Something you can almost feel. Kahuku, as one colleague put it, is "like being on another island."

Exactly.

There's something about these old plantation towns that just seems like home.

It was the Depression (the first one, the real one), and Tom Nakayama had gone from Laie Mormon school to eighth grade at Kahuku, to McKinley High. But it was 1931, and hard times forced him to leave the University of Hawaii after his freshman year.

"That time," he said, "there was no jobs whatsoever."

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Dietrich Mahlstedt sits on one of the historic pieces of machinery located on the grounds of the old sugar mill in Kahuku.

So he started going back to McKinley, pestering his old counselor for ideas, leads, advice. Finally, the teacher took him back to the North Shore. "The road wasn't paved like this," Nakayama said. "It was all coral road."

They went to the Kahuku plantation office, to meet the section boss, and a stunned Nakayama was offered a job.

The next morning, he got on the train -- they had the train then -- and went past Hauula, all the way to Punaluu. There, in a field, knee deep in water, a swamp, he cut "California grass."

Nakayama said, "I thought, 'By golly, is this the kind of job I'm going to get?'"

But there was nothing else.

Eventually, he was asked how much education he had.

"One year university."

And that was the magic key. He was given a better job. And then another. It kept coming up, every so often: "How much education do you have?" "One year university."

He worked hard. He kept the workers in mind. He had a knack with management. Then he was management, one of the few nonhaole bosses at a time when that was all but unheard of.

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Pineapples and apple bananas greet roadside travelers at one of the many fruit stands along Kamehameha Highway.

"I don't know how I did it," he said.

Then he did.

"A lot of public relations."

He became assistant manager and was offered the spacious assistant manager's house, up on the hill.

But he thought it best to stay at his house, next to the hospital.

"I been there 30, 40, almost 50 years now," he said.

In two months he'll be 91.

Spike Akiyama is 86. He worked for the plantation for almost 40 years, right up until it closed in 1971. Then he went to work at Turtle Bay.

"It's better than working plantation," he said.

"There was a theater over there," he said, pointing. "Over there was one boxing stand.

"Long time ago, used to have a wash house."

When he was a kid, growing up on the plantation, they moved all the time.

"The house get old, ah," he said.

His plantation career was different from his friend's.

"He wen' go high school, 'ass why!" he said. "Us, eighth grade, we work already."

But that, like so many things, is long over now. Akiyama sat on a bench soaking in the joy of a bon dance at the Hongwanji. There were reunions, classes that graduated from Kahuku after the high school was built in the plantation town. All of them seemed to come over, the children of his generation, to remember, and for kisses and handshakes and hugs.

Kahuku always feels like home.

BACK TO TOP |

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

Agnes Ishii, left, is owner of Rocky's Coffee Shop, noted for its fried rice, omelets and waffles.

Waipahu residents strive

to build community after

being divided by a freeway

For many decades sugar thrived in Hawaii, and Waipahu was a hub of the industry and other commercial activity, most of it centered on Waipahu Depot Road.

A line still forms at Rocky's Coffee Shop beginning at 4:30 a.m.

"I guess it is a habit for the ex-plantation workers," said Darrlyn Bunda, executive director of the Waipahu Community Association, who notes that the coffee shop is still famous for its fried rice, omelets and waffles.

Oahu Sugar Co. built its mill on Waipahu Street in 1898 and continued to operate until 1995.

Sugar may be a thing of the past, but Waipahu is "fighting back to be economically and socially revitalized," Bunda says. "We want the town center to come alive. ... We are going to be an exciting little city."

One of the first steps is to connect the surrounding neighborhoods, explained Bunda.

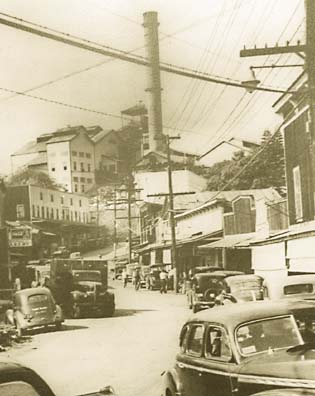

Waipahu's Old Depot Road when sugar was king.

"We are trying to build communities, not draw invisible lines," she said.

Construction of the H-1 freeway caused the town center to be divided, but the association plans to connect Village Park using the old Cane Haul Road and the Waikele neighborhood by opening the old Manager's Drive. The renovations will provide people a place to ride their bicycles or jog, she added.

Beautifying the community involved planting trees along the median of Farrington Highway. More importantly, the association seeks to restore Pouhala Marsh, formerly designated as a dump site, as a natural resource. Part of the group's "weed and seed" effort will involve the removal of mangroves around the marsh.

"We are surrounded by water but we can't even see it," Bunda said. "The roots are so thick that we have some homeless people living there."

A planned walkway along Kapakahi Stream, which runs through Waipahu Gardens, will provide a direct connection between Hawaii's Plantation Village and the Festival Marketplace -- a planned market at the former Big-Way site that will open in late 2004 or early 2005 and house at least 34 vendors offering fresh produce and seafood, Pacific regional food products and local arts, crafts and memorabilia, said Bunda. Smaller kiosks will be made available as low-cost incubator spaces for emerging entrepreneurs, she said. A business and training center, located in the marketplace, will serve the entire community.

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

Darrlyn Bunda, left, and Waipahu resident Goro Arakawa stand on Waipahu Depot Road. The town is "fighting back to be economically and socially revitalized," said Bunda, executive director of the Waipahu Community Association.

Leeward Junior Jaycees and the Hawaii Women's Business Center will provide business, financial and legal training, she added.

Bunda said she hopes the cultural flavor of the marketplace and its proximity to the Plantation Village and Waikele outlets will attract tourists and not just community members.

The Festival Market is expected to bring a revitalization of business activity in the town's core, creating at least 39 jobs and the start-up of at least 25 small businesses by 2009. The changes are also meant to reduce the unemployment rate among low- and moderate-income residents.

Bunda said it is hoped that Waipahu will regain its place as an attractive place to do business, with social benefits unheard of during plantation times.

Bunda said she envisions Waipahu as a place where "business prospers in ways that support the community goals and where its residents are trained and able to compete and prosper in a global economy."

BACK TO TOP |

CINDY ELLEN RUSSELL / CRUSSELL@STARBULLETIN.COM

Edith Ramiscal, president of the Farmer's Coop, and her mother, Luming, both work their tables of herbs, produce and canned goods at the Waialua Farmers Market.

One asset that has remained

constant in Waialua is

the people who live thereWaialua Sugar folded long ago,

but residents still love to live there

Drive down the winding, ironwood-lined Kaukonahua Road into Waialua, and you'll understand why some never leave and those who do eventually return.

It's the feeling of serenity that comes over you as you drink in the peaceful countryside and experience the slow-paced lifestyle of this once-thriving sugar plantation town, residents say.

With the Waianae Mountains as a backdrop and uncrowded beaches a few minutes' drive from the center of town, they ask: What more could you ask for? they say.

"It's just a really relaxing place," said retired schoolteacher Edith Ramiscal, who was born and raised in Waialua, left and now is back to stay. "You know you're in the country."

Very little has changed since Waialua Sugar Co. -- then the town's biggest employer -- harvested its last batch of sugar cane and shut down in 1996. The only remnants of this town's agricultural heritage is the smokestack still standing at the old sugar mill in the center of town and a large wooden sign proclaiming Waialua as the home of the world's best sugar.

There are still no traffic lights.

Community activities center around the elementary and high schools, the district park and Waialua Library, voted the best small rural library in America and the best Friends group in 1997 by the Public Library Association.

On weekends, a farmers' market at the old sugar mill site is an excuse for residents to socialize and pick up homemade delicacies and cucumber, corn and other vegetables they can't get from their own yards or their neighbors'.

The occasional cockfight also is a good place to find cheap local grinds.

At night it's so quiet that you can hear the surf in the distance or the high school band practicing. Occasionally, bikers will roar into town to make a pit stop at the only available watering hole, the Sugar Bar.

But look closer, and there are surfboard shapers, auto and boat repair shops, cabinet and soap makers, even a smokehouse, taking over the warehouses previously occupied by the Waialua Sugar Co.

The fields of sugar cane that once blanketed the hillsides toward Kaena Point and Waimea Bay have made way for corn fields, banana orchards and flower farms.

Farmers, many of whom used to work for the sugar company, are leasing former sugar cane lands to grow tomatoes, asparagus and other crops for the weekend farmers' market or for sale at supermarkets across the island.

One asset that has remained constant is the people who live in Waialua and take pride in knowing and helping one another, said longtime resident John Hirota.

"We all know each other, our roots, where we came from, the hardships we grew up with and how our parents and grandparents sacrificed," he said.

Ramiscal said, "A lot of people are related to each other because it's so small."

"So cannot talk stink," added Walter Yamada.