[ FREIGHTER FANTASY ]

CHARLOTTE PHILLIPS / SPECIAL TO THE STAR-BULLETIN

Trade Bravery headed out of the harbor and toward the Oakland Bridge as it began its voyage across the Pacific Ocean on a hazy Fourth of July.

Adventure

on the high seasBefriending the ship’s

captain and crew is a highlight

of a long-anticipated

freighter voyage

Trade Bravery is finally on the way to China, carrying 1,600 containers filled with unknown cargo. It is also carrying 19 officers and crewmen -- and me. I looked out my portholes at daybreak to see nothing but shimmering sea. It was glorious.

Leaving America was quite dramatic. It was the Fourth of July. The sun was dropping slowly in a hazy sky. We went under the Oakland Bridge and then the Golden Gate Bridge, following the Hanjin Paris, a freighter that was docked in the berth behind us in Long Beach, then Oakland. Sailboats, motor boats and tug boats looked tiny from my perch in the wheelhouse.

Capt. Ronald Karl Eckard Kellner, a gracious man who speaks flawless English with a Sean Connery accent, invited me to the wheelhouse for our departure. A pilot boarded the ship to guide us out of the harbor. After his job was done in a couple of hours, he made an amazing exit: He donned safety gear, headed to the lower deck, dropped a rope ladder over the side and climbed into a boat -- which had appeared out of nowhere, and which then quickly disappeared into the mist -- while we kept going full speed ahead.

The captain showed me our route on his chart. I thought he was joking. Why would we go toward Alaska and past the Aleutian Islands and the Bering Sea and then the Sea of Japan between the Koreas and Japan, and on to the East China Sea and past Taiwan, instead of going straight past Hawaii to Hong Kong?

But flat maps can be deceiving. He reminded me that the Earth is round and that this route is the shortest. I checked the globe in the World Book when I returned to my cabin, and saw that it is indeed the most logical route.

I feel completely at home. Just four days earlier, I had been dealing with problems getting past Long Beach Port security and Hanjin Terminal officials, before finally tackling the intimidating, swaying gangplank, only to learn that the booking agents had told no one on the freighter that I was to be its lone passenger. To get me out of the way, chief officer Steffen Mydlak, who is in charge of the ship in the captain's absence, put me in the owner's cabin on the fifth deck. And that is where I am told I shall remain. It certainly beats the bed, desk and chair on the second deck that I'd been promised in booking passage.

We loaded cargo all that first night in Long Beach, and then set out for Oakland, which we reached in about 17 hours. The shipping agent in Oakland offered the captain and chief engineer Hans-Jurgen Wendt a lift into San Francisco. They let me tag along. We spent a few hours roaming the city before returning to the ship for our 5 p.m. departure.

CHARLOTTE PHILLIPS / SPECIAL TO THE STAR-BULLETIN

The ship's officers regularly had coffee in the captain's cabin. From left, Chief Officer Steffen Mydlak, Capt. Ronald Karl Eckard Kellner and Chief Engineer Hans-Jurgen Wendt.

A little help from friends

Steffen got my balky voltage converter to work. Without converting to the European current of 220 volts, I would not have been able to charge my camera batteries or use any electrical gadgets. He also found an obscure outlet in a cabinet near the desk so I could plug in my surge protector and laptop computer, and gave me a non-slip covering for the desk and a vibration-absorbing mat for the computer. When I said I didn't think I would need the non-slip covering, he said prophetically, "You will."Steffen was my third friend aboard the freighter. My first friend was the kindhearted crewman, Ronald Sogo-An, who spotted me staring apprehensively at the gangplank and offered his help. He took my suitcase up and reported to Steffen that a woman was coming aboard. At that point, my second friend, third officer Julieto Obillos, started wiping the thick, black grease from my hands.

My computer is set up in front of one of my day room's three portholes and I am watching out the porthole to my right as the now-faint sun sets into the ocean.

Tomorrow, we will start setting our watches back one hour every night for nine nights. So we'll be on Hawaii time Monday, but only for 24 hours.

CHARLOTTE PHILLIPS / SPECIAL TO THE STAR-BULLETIN

A crewman lowered a scaffold to wash the large portholes of the owner's cabin on the fifth deck of the Trade Bravery.

Officers' mess

This is a working ship, so the officers and crew tell time by when they go on duty and when they eat. I tell time solely by when we eat. Officers' mess times are 7:30 a.m., noon and 5:30 p.m.In an island touch, we leave our shoes at the door to the officers' mess, just as we do at our cabins, so as not to track grease and soot into the carpeted rooms.

The food is quite good. At breakfast, we order eggs to our liking, or opt for cereal or something from the menu of the day: an omelet, tuna au gratin, beans and ham or potato pancakes, with coffee or tea. There are always three kinds of cheese on the table, plus butter, cream cheese, jams, condiments and two kinds of bread. Once or twice a week, yogurt is an added treat.

Lunch, the heaviest meal of the day, starts with homemade soup, which varies daily. So far, we've had noodle, asparagus, mushroom and lentil. At lunch and dinner, we have a choice of cold cuts with rye and French breads, or hot meals, which may be kebabs, chili, grilled pork chops with onions, Irish stew or German sausages. Vegetables include carrots, broccoli, cauliflower and Brussels sprouts, with lots of potatoes and onions. The ever-present bowl of salad consists of lettuce, cucumber and green pepper. We have occasional oranges, bananas, apples and grapefruit. No desserts are served except for the Sunday noon ice cream and the Thursday noon pudding.

No one except its staff is allowed in the kitchen, which is nestled between the officers' mess and the crew's mess. But I managed to meet the cook, Cipriano Eugenio, 54, just outside the kitchen door and compliment him on his cooking. The mess man, Ronel Montero, serves our food. He is 32, but looks 19. I am very fond of him. He does more than is required and always wears a beaming smile. On my first full day aboard, he knocked on my door at 10 a.m. to remind me it was tea time, and that tea time also occurs daily at 3 p.m. I told him I would skip tea. Minutes later, he brought two bottles of drinking water and put them in my fridge. The next day, when he brought me a platter of fruit, I gave him a box of macadamia nut candy, to his delight.

I descend 80 stairs each time I go to the poop deck to the officers' mess, which is easy, but then I have to go back up. I have opted out of the teas, not because I mind the stairs, but because I don't need to eat every two or three hours. I also go down to the poop deck and through the heavy outer doors when I take a stroll on deck. That lowest deck also is home to the ship's main office.

I have all my meals with the German officers: the captain, 54, the chief officer, 36, and the chief engineer, 50. They are brilliant, personable, good-humored -- and mischievous. I'm never sure when they're teasing. After dinner, the captain and I often remain at the table, discussing travel, politics and current events.

The Romanian electrician, Stelian Constantinescu, 47, is supposed to eat with us, but he speaks little English and little German, so he usually eats early, either because of his work schedule or to avoid dealing with us.

Everyone else on the ship is Filipino: the four junior officers, the crew, the cook and the mess man.

Although I try not to be a pest, I'm full of questions at mealtime, such as "What's in the containers?" I can't help but wonder what mysterious cargo may be locked inside the stacks of 40-feet-by-9-feet containers.

The officers' essential response: "We don't know and don't want to know. We aren't responsible for anything in sealed containers so not knowing saves us a lot of trouble."

Shippers must certify that there is nothing illegal or hazardous in their containers, and the shipping lines take their word for it.

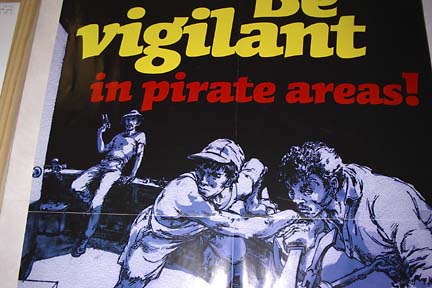

CHARLOTTE PHILLIPS / SPECIAL TO THE STAR-BULLETIN

A warning poster hangs in a hallway of the ship. Although pirates in the Pacific mainly attack in the Malacca Straits in the South China Sea, all ships must be vigilant. The Trade Bravery's intercom system would alert the crew in case of attack.

Scared safe

Today I survived my safety training, conducted in English/Tagalog by second officer Ernesto Mapa, 44. Hans-Jurgen, the chief engineer, told me with a straight face that I would have to go down the rope, just as if we were in a real emergency. It's a good thing he was kidding because it was hard enough just to stay upright on the windy, slippery deck.A warning of seven deafening short alarms plus one long alarm would indicate it's time to put on "stout" clothing and footwear, grab a life vest and head to the muster station.

I'm the only person on the fifth deck so if a fire blocks the hallways or stairways, I am to open my cabin's emergency porthole, attach the knotted rope, throw it out and head out the window to the muster station, four decks below. I can't even see the deck from my emergency porthole, just the side of the ship and the churning ocean.

If short and long signals alternate continuously, it means "abandon ship." Everyone must don stout clothing from head to toe, grab extra blankets, water and life vests, and head to the lifeboat, which is hanging nose down, above the water.

In case of a pirate attack, a "silent" alarm will sound only through our intercoms, signaling us to gather in the crew's mess room.

"Since you're in the owner's cabin," the captain told me, "we'll just send the pirates directly to your cabin so you can deal with them."

Slop chest time

The slop chest offerings have changed a lot from the days of the old Howard Pease freighter adventure books I used to read. Then, there was no booze for sale. Now, it's mostly booze: Rum, of course. After all, these are sailors. But also beer, vodka, wine, soft drinks and a few necessities, such as toothpaste.I was going to order working gloves to use on the gangplank and other greasy areas, but the captain left a pair outside my door. So I ordered a case of drinking water (12 1.5-liter bottles) and two boxes of orange juice, about 1.3 liters each. I also ordered a 5-liter box of wine to share with the officers at dinnertime, partly because no cold beverage is served with lunch or dinner, but mostly because everyone has gone to such lengths to make me feel at home.

As we sipped our wine from wine glasses the mess man provided, the captain said, "This is so very civilized." Everyone agreed. I even got a smile and "cheers" from the quiet Romanian.

I finally accepted the officers' invitation to join them in their rec room on the fourth deck, which is also where their cabins and individual offices are located. They gather each night at 8 to play darts (Hans-Jurgen is the champ but sometimes the captain and Steffen eke out a win), have a drink, chat, tell tall tales and play music or watch movies. It is warmer than on my deck. I told them that was likely because of all the hot air swirling around their deck.

The next afternoon, I was sprucing up the bamboo centerpiece in the rec room when the captain saw me and insisted I join them for tea. He said we would pass through the first of the Aleutians that evening and I could join Steffen in the wheelhouse. But the dark and the fog were working against us so we saw nothing. I hung out for a while, and Steffen showed me some of the instruments, including the radar, which indicated three other ships in our vicinity, none close enough to see. International laws require that all ships have red lights mounted on the port (left) side and green lights on the starboard (right) side, with white lights at the front and back, to avoid collisions.

CHARLOTTE PHILLIPS / SPECIAL TO THE STAR-BULLETIN

The author paused at the stern during a daily stroll of the freighter, which is 680 feet long.

Bow-to-stern tour

During my second week aboard, Steffen took me on a bow-to-stern tour. The ship's size -- 680 feet -- is astounding. It was a cold, windy day and we went up and down many flights of stairs to see this surprisingly clean ship from all angles. Some of the crewmen were out, cleaning mussels they had gathered off the ship. We watched as the ship's bow plowed effortlessly through the clear, sparkling water, shoving billows of white spume out to the sides.A few days later, Hans-Jurgen took me into the depths of the ship. Monitors in the control room let him and the second and third engineers keep an eye on every machine. The complexity of the equipment is staggering. We had to wear earmuffs to enter the area containing the seven-cylinder, 19,810-kilowatt diesel engine. There are also three 1360-kilowatt auxiliary engines and one of 1020-kilowatt power. He said our speed varies from 19 to 22 knots, with one knot equivalent to one nautical mph, or 1.15 statute mph. The thick fuel must be heated to a liquid before it can be used, and its quality has to be regularly tested in the ship's lab.

Hans-Jurgen showed me where 20 tons of sea water is made into fresh water daily. I had a sip. It was as good as any water I've ever tasted. He said water conversion is halted when the ship is approaching land, and whenever the water is dirty and murky. I also saw the sewage-treatment equipment, which uses bacteria for purification.

I was struck by the neatness all around me, with everything labeled and stored in perfect order. Still, I could have gotten lost in the maze of machinery, pipes, massive ropes, wires, and cubbyholes, so I followed Hans-Jurgen closely.

He showed me the food freezers and refrigerators, each kept at a different temperature. All temperatures are stated in Celsius. Converting to Fahrenheit is cumbersome: You have to multiply the Celsius figure by 9, divide the result by 5 and add 32. He made a chart and hung it in the laundry room for me because you have to choose specific temperatures for both the washer and the dryer. The mess man Ronel changes my bedding each week but not the towels, so I just throw them in with my laundry.

Later, Hans-Jurgen stored about 200 songs from his collection into my computer, and set up a DVD movie, "Mercury Rising," which he reprogrammed to run in English, although it was fun to hear Bruce Willis "speaking" German at first.

The captain has told me I am welcome in the wheelhouse at any time. It's one level above me, at the top of the ship. It's a magnified version of an airplane cockpit, with doors that lead out both sides onto open bridges. Steffen and the second and third officers stand four-hour watches in the wheelhouse, while the captain goes in and out at will. There is a steering wheel, but except for entering and leaving a harbor and emergencies, the ship is on automatic pilot. There is a mind-boggling array of charts, meters, instruments, lights and sounds. I checked out the global positioning system, so whenever I want to know our latitude and longitude, I can find out at a glance.

When I was up there yesterday at 7 a.m., having coffee with the captain and Steffen, we saw frenzied splashing. I was excited because they had seen dolphins and flying fish on their last voyage, but the captain said today's splashers were likely a large school of tuna. Then we saw thousands of large seabirds, either gulls or terns, in front of and on both sides of the ship. After a few minutes, they vanished as rapidly as they had appeared. We were about 110 miles from the closest land, which would be one of Aleutian Islands. Steffen said we would pass Attu at about 7 p.m. so I returned to the wheelhouse but the fog was thick and we saw nothing.

Friday canceled

Although time seems irrelevant out here, now that we have crossed the international date line, the captain says we will skip Friday entirely. By international agreement, when it is 12:01 a.m. just east of the imaginary line, which runs north and south along the 180th meridian, it is 12:01 a.m. the next day just west of the line. We will soon pass North Korea and South Korea, but they will be shrouded in heavy fog.On our 12th day out, the sea turned rough. Taking a shower was more difficult than usual. I ended up just sitting on the floor rather than continue to brace myself while kicking at the shower curtain that keeps sticking to my back in the little triangular stall.

The choppy sea forced me to use the hand railings in the halls and attach my swivel chair to the desk with its strap and hook. I also used the 18 keys positioned in the various locks to keep cabinets, closets and drawers closed. When the pitching and rolling made it impossible to use the computer or read, I went to bed and rolled around all night. But the non-slip mat kept everything on the desk in place. By the next day, the ocean's smooth glassiness had returned and we were skimming across the water, leaving flashes of turquoise and white froth swirling behind.

The portholes have gauzy white curtains, but also heavy panels with Velcro fasteners that can be used to block out the light. The one in the bedroom is helpful at this point of the voyage, when it gets light at 3 a.m.

The booking agent told me the weather would be hot, but I have been freezing and wishing for warm clothing. I don the knit cap and sweatshirt I bought in San Francisco for deck strolls. Today, I saw a Japanese fishing boat and a few soaring seagulls. Later, we passed some of the Japanese islands and I was able to get a shot of the sun dipping behind one, leaving a golden glow.

CHARLOTTE PHILLIPS / SPECIAL TO THE STAR-BULLETIN Third engineer Danilo Gonzales and a crewman cleaned the fuel purifiers in a section of the huge engine room.

Learning secrets

The sign saying "one hour retard" has been removed and the backward setting of watches has ended, but I thought we had another day of time-changing so I strolled down to breakfast at 7:30, only to learn it was 8:30 and breakfast was over. Ronel said he and the captain had phoned me and banged on my cabin door, but with the bedroom door closed, no sound could filter in above the engine's drone.The ship continues to reveal its secrets. The captain invited Hans-Jurgen and me for sunset drinks by the pool last night, while Steffen was on duty. Yes, there is a pool. Sort of. Out a heavy, locked door just before the door to the captain's cabin is his open-deck area with benches, a table and chairs, which are stacked and lashed down when not in use. The small pool is empty, but when the captain so orders, sea water is harnessed and fed through a filter to fill the pool so officers can take a swim, after which the water is returned to the sea. But it has been too cold to use the pool.

The next day, the captain said I could sit on the deck while he and the officers were busy elsewhere. I tried to read but was so hypnotized by the sea that I got little reading done. Each day I am awestruck anew as I marvel that I am on this freighter that is seemingly alone in the boundless and mysterious ocean.

I am used to the ship's constant hum, vibrations and rattling, but the thing most memorable is not a sound but a feeling, especially when lying in the bunk, even on the fifth deck, far from the engine. It's the feeling of a pronounced and constant throbbing, as if from the beating of the ship's heart.

Safety drill

We dropped anchor far from shore early today to kill time because the Hong Kong Harbor is not ready for our arrival, and the officers decided it was a perfect time for the semiannual safety drill. The alarm sounded and we grabbed our life jackets and headed to the muster deck.Part of the crew entered the enclosed lifeboat, which can hold 36 people, while the rest stayed behind to hoist it back into place after it circled the ship a couple of times. Steffen orchestrated the exercise, which was carried out to perfection. Pulling the lifeboat back up was a hassle, but had there been reason to abandon ship, we all would have been safely in the lifeboat and away from the ship within about 15 minutes.

In preparation for Hong Kong authorities, we have filled out forms to declare tobacco products, wine, spirits, cameras, laptops and jewelry. And the captain had us all take our temperatures so he could log them for officials. The requirement was for everyone to register below 37 C (98.6 F), and we all did. The officers showed me photos from previous trips, when they and the Chinese pilot were wearing surgical masks to enter Chinese harbors. I have masks a friend got for me in Honolulu, but the SARS situation has eased so I won't need them.

The captain invited me to the wheelhouse for tomorrow's 12:30 a.m. boarding by the pilot who will take us into Hong Kong waters. We have crossed the Pacific Ocean. I am happy to be off the coast of China, but I feel melancholy because my voyage is nearly half over.

Charlotte Phillips is fulfilling a lifelong desire to travel via freighter. Her earlier Freighter Fantasy stories can be found on our Web site at starbulletin.com/2003/06/22/travel/story1.html and starbulletin.com/2003/07/20/travel/story1.html.