COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS

Marie McDonald and Paul Weissich meticulously document native plants used in lei-making in their new book "Na Lei Makamae." The model wears lei of 'Ohai.

Symbolic beauty

The history and meaning

of giving lei are explained

in a new book

In "Hawaiian Antiquities," the 18th century Hawaiian scholar David Malo poetically referred to the umbilical cord not as piko but as lei, likening the cord that transmits life and love to the embryo to the floral offerings that mark every major occasion -- and nourish even the littlest moments -- as a mainstay in daily island life.

Just as the birth cord conveys food, breath, warmth and love of mother and father to the unborn child, so do lei symbolically convey love, honor, pride and accomplishment, says master lei maker Marie McDonald.

Her book, "Na Lei Makamae," co-authored with Paul Weissich, director emeritus of the Honolulu Botanical Gardens, pays tribute to a unique cultural practice and artform that, since earliest times, have cherished the "oneness" of communal bonds and the natural environment which sustains us.

"Na Lei Makamae:

The Cherished Lei"

Marie A. McDonald and Paul R. Weissich

University of Hawai'i Press, hardcover, $49.95

Newly published by University of Hawai'i Press, "Na Lei Makamae" was designed by Momi Cazimero, and features photography by Jean Cote and poems composed expressly for the book by Kumu Hula Pualani Kanaka'ole Kanahele.

"Na Lei's" "birth" will be welcomed with an exhibit of photographs from the book and a mini-festival of cultural offerings tomorrow and Sunday at Ho'omaluhia Botanical Garden and Na Mea and Native Books.

Following in the footsteps of Samuel Kamakau, Abraham Fornander and others, the authors have collected a wealth of written and oral information to reveal the significance of making and wearing lei and their role in Hawaiian ritual and dance.

"Na Lei Makamae" is, simply, a stunning book resulting from 10 years of meticulous research, writing and artistic collaboration by Weissich and McDonald to document the lore and native plants that produce the fragrant art.

In his foreword to the book, the late geographer and cultural historian Abraham Pi'ianaia observed that McDonald "has gathered her ideas the same way as she gathers the flowers that grow around her home in Waimea, and woven a lei for all of us, a lei of tradition and wisdom," in which "each lei, each explanation, each word leads us to deeper understandings not only of na lei makamae but also of who we are as native Hawaiians.

"Na lei makamae, the cherished lei," Pi'ianaia wrote, "the lei that lasts forever."

O ka lei he hi'iaka mea ho'okahi

He kahiko nou mai keia 'aina aloha maiThe lei is a reflection of oneness

From this loving land, an adornment for you.-- Pualani Kanaka'ole Kanahele

AT 77, McDonald, an ethnologist, artist and educator, has done just that. Along with her sister Irmalee Pomroy, also an accomplished lei maker, McDonald is widely credited for reviving interest in the old floral lei. She is also a master in kapa making and ipu pawehe (gourd painting) who, in 1990, was recognized as a "Master of Traditional Arts" by the National Endowment of Arts.

Weissich, who also co-authored "Plants for Tropical Landscapes: A Gardener's Guide," said the collaborative process was a joy, but exhausting as well. Dividing up the research between them, Weissich said he "read 'til my eyeballs were ready to fall out."

At one point, he said McDonald told him, "Weissich, stop reading, we'll die before this is finished, we're getting old!" he laughs. "That's when we got on the stick."

They proceeded to divide up the tasks; Weissich wrote the text, while McDonald created the lei and garments and applied the temporary tattoos worn by photograph subjects. Cote's photographs are remarkable. Without gloss or filter, we see the lei as they were worn centuries past -- a sense strengthened with these being not professional models but Hawaiians, young and old, from all islands, representing every walk of life.

"This was an important point for us, we wanted to show off our Hawaiian people, because they're a beautiful people," McDonald says. "And our culture, our rights are just as endangered these days as the lei material."

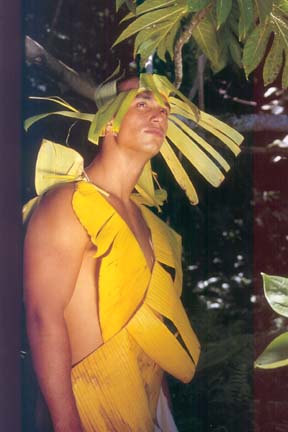

COURTESY OF UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII PRESS

Kawaiolimaikamapuna Hoe of Oahu is adorned with Mai'a, or banana-leaf lei.

IN HER FIRST book, "Ka Lei" (Topgallant Press, 1978), regarded as a source book on the history and methods of lei-making, McDonald drew on oral histories that she gathered from lei makers during the 1950s and '60s. Since sharing their knowledge and techniques with her, many have passed away, while the book remains in print after a quarter century.

Lei played an integral role in everyday Hawaiian culture, and McDonald illustrates this in "Ka Lei" through her own childhood memories. As a child, young Marie and her sisters and brothers and cousins would often be sent early in the morning to gather pohuehue vines that grow at the beach.

"Then, with vines in hand, we slowly enter the cold morning waters. Our fathers call softly, 'pa'ipa'i' and with lei of pohuehue, we slap and agitate the water sending all the fish into the net that was set out the night before. 'Pa'ipa'i' the fathers call again and the waters we slap become rough and choppy as we shoo the fish into the net. What a marvelous way to greet a new day!"

Countless generations have honored life passages large and small with blossoms strung in endless ways -- "not to mark just the joyous and happy moments, but also those filled with sadness and grief, nostalgia, accomplishment and pride," McDonald says.

Local families make and give lei to warmly greet 'ohana or friends visiting or departing, or to celebrate a birthday, graduation, or wedding. Lei of hala are also made when someone passed away. And as lei are made and given for many different reasons, Pi'ianaia wrote, "They are also made and given simply for the sake of giving. ... "There did not have to be a reason beyond the act itself.

"These customs and practices were merely in accord with the way we had been raised and taught. They were part and parcel of our everyday life, as they had been for countless generations past."

During the long period of isolation following the early Polynesian voyages until first contact with the West, Hawaiian culture evolved in new directions and its arts and sciences underwent a cultural revolution. Lei making flourished as nowhere else in the sheer variety and intricacy.

"A lei represents, in a sense, the mores of Hawaiian society," Weissich explains. "It is an essential part of daily family and community life."

Not just decorative, lei were an integral component of Hawaiian culture, ritual and dance. Broad banana lei cooled the laboring bodies of farmers tending crops. Dancers drew inspiration adorned with maile, the sacred kinolau (body form) of the patron goddess of hula Laka. Lei maile was also a peace offering on the field of battle.

According to the concept of kinolau, "A leaf, a flower, a stream did not represent a deity," Weissich explains, "but was at any moment one of the physical manifestations of that deity," commanding deep reverence and respect.

The ali'i, the ruling class, and the kahuna, the learned class of experts, wore the permanent lei of feather, human hair and ivory as symbols of power and authority.

All gathering was respectful, a spiritual ritual, and the traditional lei maker was an esteemed artist attuned to the natural world and the gods whose kinolau formed each lei. Varied materials gathered from the wild reflected nature's splendor in lei of feathers (lei hulu manu), shells (lei pupu), seeds (lei hua), as well as flowers and vines.

But today, much of the native Hawaiian flora is threatened, and many species are endangered, says Weissich. He says that one of the driving factors behind the making of "Na Lei Makamae" was to promote appreciation and conservation of native plants.

THE INTRODUCTION of new plants and animals to Hawaii upset the ecological balance and has caused the near extinction of the mamo, 'o'o, 'i'iwi, 'apapane, 'o'u and many other native species.

The authors stress that rare, endangered native plants used in lei shown in the book were harvested from cultivated sources. The book urges those who gather lei material from the wild to grow their own plants so as not to further ravage dwindling natural resources. Advancing this concept, tomorrow's ho'ike will include a sale of native plants used in lei making.

McDonald practices what she preaches. On the 10-acre organic farm that her daughter and son-in-law now manage, McDonald tends and harvests materials for her lei and kapa, including wauke (mulberry) and dye plants.

Aptly enough, McDonald's life began with a lei -- in her name Leilehua, bestowed by her Hawaiian great grandmother. "So there must be truth to what the tutu ladies say: 'Be careful what you name your child -- she will live up to it,' " she says.

"My mother showed us how to make lei, how to kui (string), simpler methods, then how to wili (wrap/wind)," McDonald says.

McDonald worked for 23 years as an arts educator with the Honolulu Parks Department. In the 1950s, she organized lei exhibition that became a life turning point. "I was mesmerized by lei that came from other islands," she says. "I had never seen such patterns and materials used before -- it was such a revelation!"

Inspired, she began to research the artform and studied with various practitioners, including Alice Namakelua and Mary Kailiano Bell. Namakelua taught her the humu papa method, to sew with needle and thread to banana or ti, and Bell taught her how to haku. "Then you just practice and practice 'til you get good," she says.

"I used to marvel how Mary, while braiding, would talk and tell a story, and her hands would be moving like she wasn't paying attention to what she was doing," McDonald recalls. "She didn't have to pay attention to technique, pick up the pansies, and just put beautiful lei together. Just ask any lei maker while they're making a lei, they're thinking not just about the lei, but about life itself.

"Now I can do that," McDonald brags, graciously. "That's when you know you've 'arrived.'"

BACK TO TOP |

Book signings

With plant sale, photo exhibit, entertainment and "Ho'ike Na Hana No'eau Hawai'i" show of works by 15 master practitioners in the arts of lei making, lau hala plaiting, decorated gourds, feather work, woodwork and morePlace: Hoomaluhia Botanical Garden

When: 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. tomorrow

Admission: Free

Call: 537-1708With "Ho'ike Na Hana No'eau Hawai'i" exhibition

Place: Native Books / Na Mea Hawaii, Ward Warehouse

When: Noon to 3 p.m. Sunday

Admission: Free

Call: 596-8885

Click for online

calendars and events.