Meth use dropping

among studentsBut experts disagree on how

best to treat addicts and prevent

even more drug use

McKinley High School students Kelly and Shelly Tuifagu say they've been pressured to use crystal methamphetamine in their neighborhood, but, like the majority of Hawaii students, they have refused.

As concern grows about the spread of the drug across the islands, surveys conducted in public and private schools offer a glimmer of hope: More students seem to be steering clear of "ice" these days.

"I think about my mom, especially, when I get pressured," said Kelly, a junior. "I don't want to disappoint her or bring shame on my family."

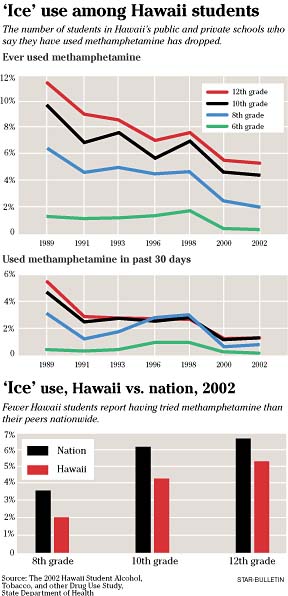

The number of high school seniors in public and private schools who say they have tried methamphetamine has fallen steadily to 5.3 percent last year from 11.7 percent in 1989. Those who acknowledge using ice in the past 30 days dropped to 1.8 percent from 5.5 percent.

"The student population seems to be growing aware of the risks associated with methamphetamine use," said Renee Storm Pearson, principal investigator for the 2002 Hawaii Student Alcohol, Tobacco and Other Drug Use Study, sponsored by the state Department of Health.

"Meth use among students was alarmingly high from 1989 to 1998," she said. "Now that meth use is dropping among our youth, we are likely to see it dropping among our young adults in a few years."

DEAN SENSUI / DSENSUI@STARBULLETIN.COM

Dr. Renee Pearson talks to teachers at Leilehua High School about health surveys that will be given to students.

The anonymous written survey, given to sixth- through 12th-graders in all public and a third of Hawaii's private schools, reflects only those adolescents who are actually attending school. But another statistic indicates that meth use among teenagers as a whole is not spiking up the way adult use appears to be.

The number of adolescents in Hawaii being treated for ice as their primary drug has remained relatively steady over the past several years, according to state Department of Health figures. One of every 10 adolescents treated for substance abuse statewide is hooked on ice, the same as in 1998. That was 158 teens out of 1,552 treated in 2002, and 189 out of 1,821 treated in 1998.

Meanwhile, the number of adults being treated for ice addiction has nearly doubled to 2,730, or 43 percent of the total treated for substance abuse in 2002, up from 26 percent in 1998. That makes ice now their primary drug of choice, while teens still abuse mostly marijuana and alcohol.

Crystal meth keeps a low profile on school campuses. Unlike marijuana, the drug has no telltale smell. Few students, in any case, risk pulling out ice pipes on campus.

"If I was smoking ice, why would I want to be in school?" asked Mike Taniguchi, who tried the drug for the first time at a friend's house in eighth grade and soon progressed to regular use. "You'd rather be at a house because of the paranoia and everything."

Taniguchi, now 20 and sober for four years, said he did not smoke on campus but did miss a lot of school. By his freshman year he was getting high so often that he dropped out. He wound up jailed for burglary at 16, a "lucky break" that got him seven months in residential treatment and a new start.

Ice is a major problem among teenagers whose drug use is so heavy that they need inpatient care. At Bobby Benson Center, a third of the patients admitted in the first half of this year abused ice primarily; at Maui Youth and Family Services, the ratio has grown to half.

While such chronic users tend to drift away from school, the drug's effects do show up on campus. Users come to school edgy and punchy.

"In school we don't see much crystal meth itself," said John Hammond, vice principal at McKinley. "We see the results. It manifests itself in behavior and in absenteeism and grades going south very quickly.

"The other way we find out is when students get in trouble with the law for fighting, stealing, whatever. Their probation officers will test them and find they're positive for that particular substance," he said.

Concern about ice use among adolescents has prompted calls for drug testing in schools, an idea championed by Lt. Gov. James "Duke" Aiona, host of next week's statewide drug summit. Legislators deferred the proposal earlier this year, raising privacy and cost concerns.

A small private school, Academy of the Pacific, has hired a drug-sniffing dog to check student lockers and backpacks. Mid-Pacific Institute is consulting with parents about the possibility of testing its students for drugs or using a dog to sniff for contraband.

Advocates argue that testing will deter students from using drugs and help identify those needing help. City Prosecutor Peter Carlisle has said test results would not be used in a punitive manner.

"The whole idea is not to kick these kids out of school," he said. "The idea is to figure out who has a problem and fix it. This is a classic prevention tool."

But others suggest the state's limited funds should instead go into expanding treatment programs and prevention, including athletics. A federally financed study of 76,000 students nationwide, published in May in the Journal of School Health, found drug use just as common in schools with drug testing as in those without it.

The need for substance abuse services for teenagers far exceeds what is available in Hawaii, both inpatient and outpatient, officials say. There are only two residential treatment programs for adolescents in the state.

"To impose random drug testing on Hawaii's schoolchildren at a time when the data show a reduction in ice use in the schools sends a mixed message," said D. William Wood, University of Hawaii sociology professor and a member of the Drug Epidemiology Work Group of the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

"We might better consider the programs in the schools that appear to have been responsible for those positive changes and put resources into them," Wood said.

The state Health Department pays for substance abuse counselors in 29 of Hawaii's 44 public high schools and three of its 56 middle schools, and would like to cover more campuses, according to Elaine Wilson, chief of the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Division. The network is designed to reach kids early, when they start experimenting.

"One of the powerful things about school-based treatment is that it gives us the opportunity to intervene with teens prior to them losing control of their drug use," said Tony Pfaltzgraff, co-executive director of the Kalihi YMCA, whose counselors work in schools. "It's more cost-efficient. To get kids who are abusing to stop is a huge gain for society."

In the confidential 16-week program, counselors help kids come to grips with their substance abuse and identify the consequences of their behavior.

They build positive relationships through activities that show teens how to have fun without drugs.

For some students the program offers a lifeline. Sierra, who is entering her senior year at a Windward high school and asked that her real name not be used, started using marijuana and alcohol in seventh grade. Until earlier this year, she managed to avoid the ice that had hooked her sisters. When she tried it, she was shocked.

"It's nothing like weed," she said, an earnest look in her brown eyes. "It's so addicting." She credits the substance abuse counselor at her school with helping give her the strength to step back from crystal meth, along with pot and alcohol.

"She talked me out of it," Sierra said. "I didn't want to want to end up like my sisters. My sisters are drug addicts and have been since they were young."

Experts say early intervention is important with teenagers, whose brains are still developing and may be shaped in part by their experiences, including drug use.

"Ice causes some of the most severe cognitive impairments that you see with any drug," said Colleen Fox, director of adolescent services at Hina Mauka. "That makes ice users a particularly difficult population to treat."

Catherine Bruns, executive director at Bobby Benson, said patients discharged from residential facilities like hers need intensive outpatient care that is not available for adolescents in Hawaii.

"They're in the beginning stages of learning to cope with their addiction," she said. "These changes aren't cemented."

A study by the state Alcohol and Drug Abuse Division last year showed that nearly half of adolescents sampled six months after treatment for drug and alcohol abuse had not used any substance in the previous month. Ninety-five percent were in school, vocational training or employed.

In some cases, school counselors suggest strategies that may not be taken to heart until months or years later, when teens come face to face with the consequences of their drug use.

"When they're ready to make that change, they know where to come," said Charlee Mallott, co-executive director of the Kalihi YMCA. "It's not as if they have to know a doctor or go down to some office building. We're there."

Sixteen-year-old Joshua grew up on the North Shore in a home where, instead of food, his mother's boyfriend cooked crack cocaine on the stove. Their fridge was always empty. Joshua (not his real name) went to school just to get lunch.

Much of the time, he and his friends ran wild, "jacking" people -- assaulting them for their money, jewelry, even their shoes -- in hopes of trading them for ice.

"I feel bad about it now, all the people we beat up," he said, a black knit cap pulled tight over his brows.

He has been clean now for six months, living with an aunt in a healthy environment, but knows he has a long way to go in recovering. "Like multiplication," he said with a sheepish look. "I know I knew that before. How come I don't know it now?"

The substance abuse counselor at his old school recently agreed to work with him again even though he is no longer in her district. She was the first adult, he said, ever to earn his trust.

"If my mom could do this to me," he pointed out, "who am I going to trust?"

BACK TO TOP |

Hearing to look

at impact of 'ice'

Lawmakers studying the state's crystal methamphetamine problem plan to look at the drug's impact on adolescent groups at a Capitol hearing today.

Among the issues the Joint House-Senate Task Force on Ice and Drug Abatement plans to examine is the growing number of island children caught in homes where one or more parents abuses the drug known as "ice."

Judge R. Mark Browning, of the state's Juvenile Drug Court program, and Judge Bode Uale, of Family Drug Court, are scheduled to testify before the committee. Others scheduled to speak to the panel include Sylvia Yuen, a professor at the University of Hawaii Center on Family, and Elaine Wilson, director of the state Health Department's Drug and Alcohol Abuse Division.

Lawmakers also plan to speak to legal professionals about constitutional issues related to Hawaii's search and seizure laws.