Makua fire

puts pressure

on ArmySome groups question

how much additional harm

a new Stryker brigade

might bring

Some Hawaii environmentalists are asking whether an island state often called the "endangered species capital of the world" is the right place for the Army's new Stryker combat brigade.

And they point to last week's Makua Valley fire -- where an Army controlled burn got out of control -- as an example of the Army not living up to its environmental promises.

"It is a serious question whether our islands, with their limited land mass that is very concentrated with people, cultural sites and sensitive ecosystems," are the best site for a Stryker brigade, said David Henkin, the Earthjustice attorney who represented the group Malama Makua in its lawsuit that sought an end to live-fire training in Makua Valley.

"It bears careful analysis."

That analysis is supposed to come soon in an environmental impact statement. However, Army officials will not talk about the contents of the 1,500-page draft document until Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld announces whether Hawaii will get Strykers. That announcement could come this week.

The Strykers are eight-wheeled armored troop carriers that are the centerpiece of the Army's "transformation" to a lighter, quicker fighting force. If Hawaii is selected, it will be the fourth location of a Stryker brigade. The others are in Alaska, Washington and Louisiana.

Col. David Anderson, commander of the Army Garrison in Hawaii, said he believes the study will show that transforming the 25th Infantry Division's 2nd Brigade to a Stryker brigade will not be incompatible with protecting the environment.

"We're searching for the optimum solution to a very complex situation: How do we get training while reducing, minimizing or eliminating the impact on wildlife, vegetation and cultural resources?" Anderson said recently.

"I think we can achieve that balance and do the transformation here in Hawaii."

There are 61 threatened and endangered species at Schofield Barracks and its affiliated Pohakuloa Training Area on the Big Island, according to a 2002 Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement, which dealt with the Army's total transformation plans. The number represented half the threatened and endangered species present at a total of 23 Army installations surveyed, the report said.

The presence of threatened and endangered species requires the Army to consult with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service about how it will protect and help those plants and animals. Hawaii has 317 endangered species listed with the service.

As one condition of its use of Makua Valley, the Army is to have an effective fire management plan that is approved by the Fish and Wildlife Service.

The Army's EIS for Hawaii goes into "excruciating detail" about the Stryker transformation and also will consider the "cumulative effect" of current and past Army actions, plus the proposed new ones, Anderson said.

Environmental activists said they hope that is true.

"Clearly, the Army needs to back up and take responsibility for cleaning up the devastation on lands that they've already created," said Cha Smith, executive director of Kahea, the Hawaiian-Environmental Alliance.

The fire at Makua Valley "underscores our concern about the Army expansion and the introduction of 19-ton machines that are going to further destroy fragile resources," Smith said.

"We'll be particularly interested in whether they look at alternatives," said Earthjustice's Henkin. "Unfortunately, there's a bad track record here, where Army commits to a course of action and puts out documents that justify that decision."

On Tuesday the Army started a controlled burn of 500 acres of brush in Makua to clear unexploded ordnance and create easier access to cultural sites. By Thursday the fire had scorched about 2,500 acres.

In preparing its environmental impact statement, the Army in Hawaii has not cost-compared with other possible sites. That would be up to the Department of Defense, Anderson said.

But even if it does cost more to locate a Stryker brigade in Hawaii, Anderson said that in his opinion "the strategic significance outweighs any additional cost that may be incurred."

In the 100 community presentations the Army has made about its expansion plans over the past two years -- about half on Oahu and half on the Big Island -- it showed a map of conflict "hot spots" around the globe and emphasized Hawaii's proximity to Asia.

One of the selling points of the Stryker is its ability to be flown quickly to conflict spots.

If approved for Hawaii, the Stryker vehicles will not start arriving right away. But over five years, construction projects to support the transformed brigade would cost nearly $700 million, arguably the largest Army building project since World War II.

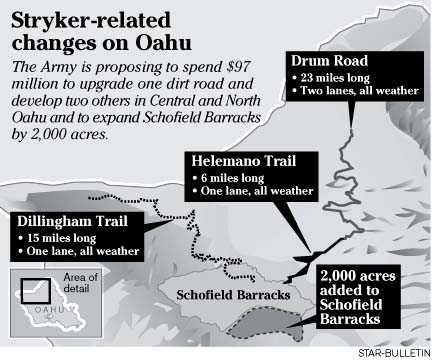

The to-do list includes:Not all species present on Army lands will be affected by the Army's proposed actions, said Joel Godfrey, the Army's natural resources program manager.» Improving rough trails into roads for military use, most significantly between Schofield Barracks and the Kahuku Training Area on Oahu and between Kawaihae Harbor and Pohakuloa Training Area on the Big Island.

» Redesigning live-fire ranges at Schofield and Pohakuloa to accommodate a greater variety of training scenarios.

» Adding a new, 23,000-acre maneuver training area for the Strykers at Pohakuloa, which will not include live fire.

» Adding about 2,000 acres to Schofield's holdings, to house Stryker maintenance shops and a new weapons training range.

"Most of the threatened and endangered plants are at upper elevations that are not maneuverable by the Strykers, so the impact is relatively little," he said.

But things like the effects of dust or possible introduction of invasive plants along Drum Road through the northern Koolau Mountains need to be examined, said Patrice Ashfield, a Fish and Wildlife Service liaison to the Army. In addition to commenting on the Army's report, the service will make its own assessment of possible effects, she said.

"None of what we are doing will depend on any waiver of current environmental regulations," said Ron Borne, the Army's transformation manager for Hawaii.

Kahea's Smith questions whether it is realistic to count Army spending as a benefit to Hawaii.

"As controversial as these things are, I think that the taxpayers here need to take a hard look at the benefits, and our decision-makers need to examine what the true benefits are," Smith said. For instance, she asked, how much did last week's fire in Makua Valley cost taxpayers?