CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

Edith Leiby, foreground above, and Charlotte Johnson demonstrate how the scan is done.

3-D scanning can

resolve heart puzzlesAn electron beam allows

angiograms to be noninvasive,

less risky and faster

Three-dimensional images of the insides of her coronary arteries told Honolulu Marathon runner Edith Leiby, 80, she can continue to exercise.

Leiby, who has participated in 17 marathons since 1975, said doctors told her not to walk or exercise after a heart attack and a triple-bypass operation in 1996 during a visit to Las Vegas.

"She has a very complicated heart problem with bypasses," said cardiologist Roger White, medical director of Holistica Hawaii, a medical scanning facility at Hilton Hawaiian Village.

"They didn't know if the surgery was working. We were able to give her reassurance. Her arteries are open. We encouraged her to exercise."

White obtained a detailed three-dimensional image of Leiby's heart with an electron beam angiogram.

With a regular angiogram, contrast dye is injected through a catheter that is usually inserted in the groin area and guided into the heart and coronary arteries for X-rays.

With an electron beam angiogram, the dye is injected through a small IV in the arm for 3-D CAT scan images looking into the heart at arteries and blood flow. Computed Axial Tomography scan, or CAT scan, is the process of using computers to generate a three-dimensional image.

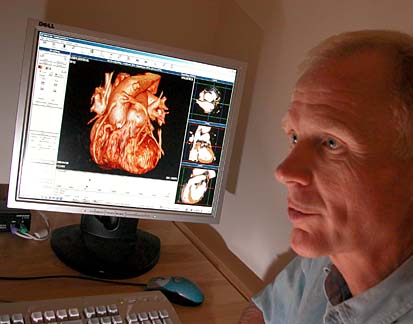

CRAIG T. KOJIMA / CKOJIMA@STARBULLETIN.COM

Dr. Roger White explains the technique while an image of Leiby's heart is displayed on his computer screen.

"Virtual imaging of coronary arteries is done in fewer than a dozen places in the world," White said.

After observing the new technology, Dr. Edwin Cadman, dean of the University of Hawaii John A. Burns Medical School, said it will benefit heart patients and is "only in its infancy and will be further developed for body scans.

"We will not need to do most interventional radiology in the future, except for complex cases," he said. The technology also provides an opportunity to study the effects of cholesterol-lowering drugs to reduce plaque blockage of arteries, Cadman said.

White said Holistica has the technology because of Dr. John Charles Klock, the facility's co-founder and chairman, who owns biotechnology companies in California and developed software for the new angiogram.

The system includes a $2.5 million scanner and computer equipment costing $1 million, White said.

The electron beam angiogram is used for people known to have heart disease to determine how severe it is and whether they can be treated with medicines, diet and exercise or should be referred to a cardiologist for surgery, White said.

He learned the technique last year at the University of California-Los Angeles, where it was developed, he said.

Charlotte Johnson, Holistica CAT scan technician, said the electron beam angiogram is noninvasive, less risky than cardiac catherization and much faster, with a scan time of 100 milliseconds. This is 2 1/2 times faster than conventional CAT scans, she said.

The computer puts together 60 or 70 images to generate a 3-D picture, she said. "We can freeze-frame the motion of the heart and get better pictures with contrast to see the blood flow."

Leiby said she had a full body and head scan April 13 last year to check on her health. "Dr. White said everything was OK. I just had a little deterioration in the brain," she laughed.

White invited her to return later that month as the first bypass patient in a series of tests to show doctors how the new angiogram works.

"They put me in a machine, then watched how my bypasses operated," she said. "They could watch my heart beat and everything running into the heart. They showed me everything on the computer and a disc."

Leiby said she was surprised to see the old clogged arteries in her heart. "They said, 'Boy, you really needed that bypass.'"

Comparing regular individual images with the 3-D pictures, White said, "The difference is incredible."

He flipped the virtual heart around, looking at the sides, the front and underneath to see the three open bypasses. "The technology is so clear. You don't have to be a cardiologist trained 30 years to know it's working," he said.

"Doing this virtual imaging, looking inside the heart, is where the future lies in diagnosis," said White, former chief of surgery at Straub Clinic & Hospital. "It's expensive now, but I'm convinced it will become standard technology."

Leiby, a former physical education teacher and sprint runner who lives at the Ilikai, said her heart problems changed her life.

She was in Las Vegas with a golf group in January 1996 when she suddenly began gasping for air. She was taken by ambulance to the hospital and had surgery the next day, on Martin Luther King's birthday, she recalled.

She walked her last marathon in 1997 and now takes care of a tent for a women's running club at the marathons. Art therapy during a cardiac rehabilitation class at the Queen's Medical Center also gave her a new interest.

She went to Paris on a UH study-abroad program to study art and French history, took art classes at UH and is painting now at Kapiolani Community College. "I'm having fun, all because of a heart attack," she said.