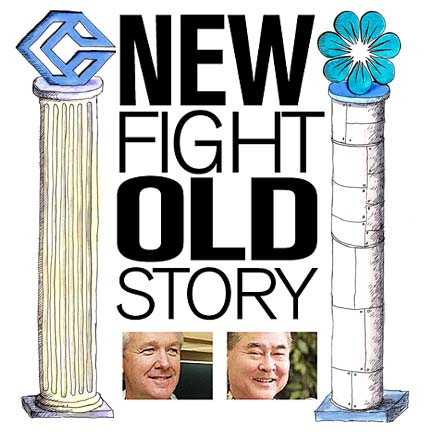

SCRIPPS HOWARD NEWS SERVICE, BRYANT FUKUTOMI / BFUKUTOMI@STARBULLETIN.COM

Both CB Bancshares' Ronald

Migita and Central Pacific's Clint

Arnoldus have been through

bruising bank battles before

It's been so quiet lately in the Hawaii bank war that you could hear a money clip drop.

Central Pacific Financial Corp. is still pursuing its unsolicited bid for rival CB Bancshares Inc. but is focusing on obtaining regulatory approvals.

City Bank's parent is on hold, uncertain if a sweetened offer or another legal challenge is waiting in the wings.

Now in its fourth month, this banking brouhaha shows no signs of ending anytime soon. But this isn't the first time that the two marquee combatants, CPF Chief Executive Officer Clint Arnoldus and CB counterpart Ronald Migita, have been in the trenches of banking warfare.

The hostile takeover. The proxy fights. The personal attacks. The power struggle. Even the "this isn't how you do business in Hawaii" rallying cry. They've seen much of this before.

Arnoldus left his job as chairman and CEO of First Interstate Bank of Nevada in 1996 when the Los Angeles-based parent company, First Interstate Bancorp, was acquired in an $11.3 billion hostile takeover by Wells Fargo & Co. that involved a bidding war with First Bank System Inc. Ultimately, more than 12,000 employees were laid off, about a quarter of the newly merged company's work force. First Interstate employees took the biggest hit as more than 80 percent of them were terminated when Wells Fargo sold or closed more than 500 branches. Customers left in droves amid computer and processing snafus that included misplaced deposits.

The merger ended up being a bust, according to news reports and analyst Joe Morford, who covers both CPF and Wells Fargo for RBC Capital Markets.

For Migita, hostile takeovers are new, but not proxy fights. His latest proxy skirmish was May 28 when CB shareholders rebuffed a CPF proposal that would have allowed it to acquire a majority of CB shares. But Migita was in the thick of a heated proxy battle over board seats during the mid-1990s that briefly cost him his job during a power struggle for the bank's top position.

In what is a familiar refrain in the current CPF-CB takeover battle, CB's then-Chairman and CEO James Morita told shareholders in a 1996 letter that New York-based investment banking firm and shareholder M.A. Schapiro, which was attempting to place two outside directors on CB's board, had "no apparent knowledge" of Hawaii's culture, economy and banking community.

Migita recently took the same tack when he said Arnoldus' takeover tactics are "not how we do business in Hawaii."

The two-year proxy fight between CB and Schapiro started in 1996 when Schapiro, now out of business, sought board representation because it was dissatisfied with both the CB's financial performance and management. Schapiro, which owned 6.2 percent of CB's shares at the time, was a market maker in CB's stock and had been a financial adviser to the bank before CB terminated that arrangement.

Schapiro also objected to a newly implemented "golden parachute" plan that would allow senior management to retain their salaries and benefits in case of a takeover or if an outside investor were to purchase a big stake in the company. And it accused Morita of nepotism for having the company nominate his daughter, Caryn, a CB senior vice president and general counsel, for a board seat. Schapiro objected to her "less than three years" of banking service while CB pointed out that she had served as a deputy attorney general between 1988 and 1993.

Caryn, currently corporate secretary at CB, did not return a call seeking comment.

Schapiro's board nominees for the May 1996 shareholders meeting were William Griffin, a fund manager and former executive at Hartford Fire Insurance, and Clifton Whiteman, a former executive vice president of Bank of Tokyo Trust Co. But CB management's nominees, Caryn and Vice Chairman Robert Taira, prevailed with 60 percent of the votes despite Schapiro's heavy institutional support.

Five months later, Schapiro's financial concerns were validated when the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco found problems with the bank's financial operations during an inspection. The bank, which had integration problems after acquiring International Savings & Loan in 1994, was forced to enter into a memorandum of understanding that imposed dividend restrictions and forced CB to get approval for executive compensation and organizational changes. CB remained under the memorandum until April 28, 1999. ISL, following several postponements, eventually was merged with CB in July 2000.

"The Federal Reserve Bank found (CB) to be a problem bank because a very high percentage of declining earnings were going out in the form of dividends and, in addition, the bank's problem loan portfolio, where loans are put in a nonperforming category, was climbing," Whiteman said Thursday from his home in Oyster Bay, N.Y. "Something had to be done, and done fast, to keep the bank from being shut down."

To complicate matters, Whiteman said "shareholders in the islands became immediately fired up about the problems of management" and Schapiro took advantage of that by gearing up for another proxy battle.

With the management and board's job security uncertain, Morita fired several executives, including Migita and International Savings Vice Chairman Lionel Tokioka, in November 1996.

"Morita thought, 'I'm going to clean these guys out. They're my enemies,' " Whiteman recalled.

CB announced Migita's departure in a Nov. 27, 1996, press release that said it was part of a previous plan to merge City Bank and International Savings and Loan. The departure, though, came 18 months after Migita, a 29-year employee at Bank of Hawaii, had been named CB's president and chief operating officer and had been given a five-year contract with a base salary of $225,000 a year.

"That was just gobbledygook," Whiteman said of the announcement. "That was as good a way as any to explain the sudden decision to remove Migita."

Whiteman said Migita had been induced to leave Bank of Hawaii with the promise that he would be succeed an aging Morita within a couple years.

"But Morita wasn't willing to follow through and had a wild idea of the possibility of his daughter succeeding him," Whiteman said. "So he isolated Migita and, as Morita shifted allegiance, he increasingly left Migita out in the cold. Finally, he decided to fire him."

Migita and the other executives later threatened to sue, according to filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission.

"This was very clumsily done by Morita and his little cabal of advisers," Whiteman said. "It was just full of both legal and external missteps. It was a function of a panicked CEO and his surrounding advisers."

But that wasn't the end of CB's problems.

The bank was forced to slash its quarterly dividend to 5 cents a share from 32.5 cents to comply with its memorandum of understanding with the Federal Reserve Board.

In addition to the unhappy shareholders, CB was facing another proxy fight at the April 1997 annual shareholders meeting. CB decided to cut a deal with Schapiro. The compromise, Whiteman said, was that he and Schapiro Vice President Donald Andres, who is still on the board, would be on the management slate of nominees; Morita, the co-founder of the company, would relinquish all his executive titles; Migita would be brought back to assume the positions of president and CEO; and some aging board members would retire.

In a February 1997 press release, CB announced that Morita, then 83, would relinquish all executive titles by that April's shareholders meeting and that a search committee would seek a successor. Less than three weeks after that announcement, Migita was named president and CEO of CB Bancshares. Morita, who had been a prominent attorney before he turned to banking, was re-elected as director and named chairman emeritus at the April meeting. He died in 1998.

"Migita was very much involved (in the deal), but he was sort of behind the negotiating front that was led by James Kamo, the bank's corporate secretary," Whiteman said.

Migita downplayed his involvement during a recent interview with the Star-Bulletin.

"Back in 1996 or 1997, I had just come on board and really I was not personally involved with what was going on," Migita said. "It was my predecessor, Mr. Morita, so it's difficult for me to make a comment on something I was not directly involved in."

On Thursday, Migita, speaking through his spokesman, Wayne Miyao, said he didn't think bringing up the past was relevant to what is happening today.

"We feel that the circumstances are different," Miyao said. "One was a proxy fight while the current one is a hostile takeover attempt," he said. "As far as we're concerned, the (proxy fight) story is ancient history and not important to what is going on now. The parties that were involved worked out their differences satisfactorily."

Still, the past has become relevant because CPF has accused CB's board and management of entrenching themselves -- an accusation that Schapiro first brought up seven years ago under CB's previous regime. CB also has on several recent occasions reached back to the past to bring up Wells Fargo's botched hostile takeover as an example of what effect a merger could have on jobs, customer service and the community.

A 1997 SEC filing reveals that Migita's selection as president and CEO was contingent, among other things, on the settlement of his claims. That agreement included nominating him for the board of directors, appointing him president and CEO of CB, reaffirming his employment agreement, allowing him to retain all compensation since he was terminated, reimbursing him for legal expenses and costs up to $8,000, and recommending his appointment as CEO of the subsidiary, City Bank.

The bank also came to terms in May 1997 with current CB Chairman Tokioka and two other former executives, Warren Kunimoto and Helen Kwok, according to an SEC filing. The three had been terminated along with Migita, and were threatening to file a lawsuit. The settlement of claims totaled $256,000 and included a lump-sum payment of $100,000 to Tokioka as well as giving him a 12-month renewable consulting contract with CB worth $150,000 a year.

Whiteman, who served on the board from 1997 to 2000, believes Migita should reconsider CPF's $286 million offer. Whiteman doesn't own any CB stock but has an exercisable 10-year option at a price of about $17 for about 1,450 CB shares.

"They are running enormous personal and financial risk by denying an appropriate opportunity for the shareholders to benefit from this extraordinary offer," Whiteman said. "I can appreciate that they're going through all these machinations because this could harm a number of employees in the bank. But, every merger does -- particularly when the competitors are in the same marketplace."

Despite disagreeing with Migita's stance, Whiteman, who turns 78 later this month, said he respects Migita's abilities.

"He's a young 61 and he had a wonderful experience with the Bank of Hawaii," Whiteman said. "His credit judgment is absolutely unerring. He's cleaned up a lot of poor loans (at CB) that the bank made under the previous management, particularly some real estate deals.

"His provision for loan losses has always been extremely conservative and the bank has maintained consistent incremental earnings improvement quarter by quarter."

Whiteman also said Migita has "a great deal of compassion" for his employees.

Arnoldus, who was the first non-Japanese to take over Central Pacific Bank's parent when he was named chairman, president and CEO in 2002, couldn't do anything wrong his first year when his aggressive marketing of the bank helped its stock surge 86.7 percent. But his announcement in April of this year that he was making a bid for CB divided the community and rubbed some other Hawaii banking CEOs the wrong way.

Now, Arnoldus is in the hot seat as he tries to overcome CB's opposition to the deal.

"I'm sure it's not over yet," said Morford, the analyst. "(A takeover) could still happen. I don't know how to handicap it at this point."

Even though Arnoldus was on the receiving end of the Wells Fargo-First Interstate merger, it's that merger which CB executives keep pointing to when arguing why a merger with CPF won't be successful.

"What started off as a great cost-cutting program ended up in disaster as the company went down in flames because customers defected in droves," said Richard Lim, president and chief operating officer of City Bank. "In their preoccupation with cost cutting, they failed to preserve the franchise and ended up destroying shareholder value. Mr. Arnoldus' tactics are quite similar to those used by Wells Fargo. Start with a media blitz and, if that doesn't work, engage in prolonged litigation. Then, if you win, cut, cut, cut."

William Siart, chairman and CEO of First Interstate's holding company, echoed those same concerns in a 1996 press release.

"Our communities would suffer a devastating blow should Wells Fargo be allowed to acquire First Interstate and execute its radical strategy of massive branch closings, layoffs and its 'take-it-or-leave it' attitude of forcing customers and businesses into electronic banking and other alternative delivery systems," Siart said.

He also expressed concern about reduced banking competition and Wells Fargo not being able to adequately serve First Interstate's small-business and middle-market customers. Those are the same concerns that CB has expressed about CPF's merger proposal.

Siart, as he looks back at the merger today, still shakes his head.

"Wells Fargo put their own people in each one of the positions and screwed it up badly," Siart said Friday.

"They believed they knew how to combine banks both peoplewise and systemwise and they were woefully inadequate in both," added Siart, chairman of the nonprofit Excellent Education Development in Santa Monica, Calif. "What really happened is they lost over 10 percent of their deposit base in Nevada, Oregon and Arizona, which were part of their revenues. So they had significant cost savings but they lost significant revenues. The important thing is to focus on your customers, which Wells Fargo forgot."

Arnoldus, Siart said, knew what was going on but wasn't involved with the takeover since he was running First Interstate's Nevada subsidiary, which had $3 billion of the corporation's $60 billion in assets. Siart said the defense of the hostile takeover from Wells Fargo was done at the corporate level.

"Actually, Wells Fargo's offer wasn't a bad idea, it was just poorly executed," Siart said. "We did have too many company banking offices and we did need consolidation. We weren't concerned about the idea. We were concerned about the execution. It turned out we were right.

"At First Interstate, it was understood that people always came first. And it's my sense that (Arnoldus) would still do that at Central Pacific. He was the head of corporate banking in Nevada, then the head of our southern Nevada region and then the president of the bank and, in all cases, he did a super job taking care of customers, which was our business strategy. That's why our revenues and profits went up over 10 percent for 10 years in a row."

Arnoldus said Thursday he's learned some lessons from Wells Fargo's mistakes.

"Going through any experience teaches you a lot," Arnoldus said. "As for the Wells Fargo-First Interstate Bank takeover, there are very few similarities with our proposed merger. One of the key lessons, though, is the importance of a smooth integration."

Arnoldus said CPF and CB are a better match because they have similar histories, a similar focus and commitment to the small businesses and people in the communities, and similar technologies.

"Such similarities are critical factors in why this merger makes so much sense and will help to ensure a smooth integration process," Arnoldus said. "This represents a sharp contrast with Wells Fargo-First Interstate.

"That merger involved banks with completely different cultures and inconsistent technologies and that were separated by large distances geographically, all of which contributed to the difficulty of integration."

Arnoldus said he wants to retain the best employees no matter which bank they come from, which differs from Wells Fargo's elimination mostly of First Interstate employees.

Arnoldus also said that decisions involving a CPF-CB merger will be made in Hawaii. Wells Fargo, he said, made decisions in distant markets "in which they were unfamiliar."